IMAGINAL REALM

IMAGE FORMATION

This is the beginning of what is from the beginning distinctly human consciousness: Freud considered the basis of image formation to be dream-work. The reason the model has the sun on the side of consciousness and the moon on the side of sub-consciousness is because human consciousness awakens and establishes itself with the circadian rhythm. To focus and concentrate requires a good night’s sleep (especially for an infant) and significant disruptions of the circadian rhythm are associated with health problems such as cancerous cell division (link).

Although the senses form within the womb, image formation occurs when the infant can experience things with the full array of senses to explore how a thing feels, smells, tastes, sounds and looks. In Spanish, the phrase for “giving birth” is “dar a luz”: “give to light,” thereby adding the most distal sense to the formation of images. Newborns are interested in things, but tend to be most interested in people. This is good because usually mothers provide what the infant needs: nourishment, cleaning, comfort and play. The infant’s focus on “savoring” is exemplified by the importance of mother’s milk (as Pope Francis has reminded us).

Perhaps the hallmark of image formation is signaled by the “bright-eyed smile” the infant reflects back to a smiling mother, showing that the infant recognizes the mother and that the infant’s mirror neurons are functioning. It is significant that human eyes have white sclera that highlight the direction of pupil focus, thus allowing an observer to follow another person’s gaze. In this sense, the “bright-eyed smile” shows the mirror neuron reflex of registering direct eye contact with the mother. Human infants spend twice the amount of time as other primates in direct eye contact with their mothers (Michael Tomasello et al., 2007; “Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: The cooperative eye hypothesis. Journal of Human Evolution, 52, 314-20). As a result, infants develop the ability to attend to reality mutually with the mother; this developing mutual attention, along with the vocal/auditory system, results in the acquisition of language.

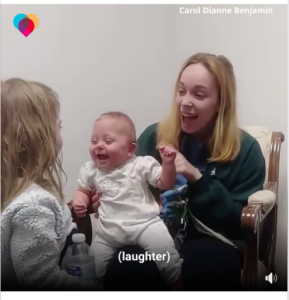

The auditory system is significant from the beginning, as can be observed from the experience of deaf children (see the gleeful reaction of a

Baby can hear, and baby laughs!

previously deaf infant to his mother after getting ear implants (link). Music is a human cultural universal, and the two most universal genres of music focus on the two ends of the life cycle: lullabies comfort the newborn while laments comfort those left with the loss of life. Lullabies not only comfort the newborn, but also the mother and fetus in the womb, supporting healthy fetal development. Lulling the baby into slumber helps establish the important circadian rhythm that leads to the alert “bright eyed smile” that helps cement the mother-infant bond. On the other hand, stress hormones transmitted from the mother to the fetus can inhibit the child’s long-term abilities to manage anxiety.

Music plays an essential role in healthy development and musical analogies permeate our lives. The mother’s “attunement” to the infant paves the way for the infant’s attachment to the mother. Throughout our lives we say that ideas and relationships that are near and dear to us “resonate” with us. Music helps us sustain our work effort (work songs) and the musical metrics of poetry made possible the oral history and transmission of core cultural narratives called epic poems (Homer’s and Moses’ stories were memorized before being written down). Romancing is done with a flute or harp and maybe singing, making it significant in mate selection. These things, along with the infant getting a good night sleep aided by lullabies, show that the theory that music plays no essential survival or evolutionary role (Steven Pinker) is tone deaf. The only way to maintain such a ridiculous theory is by separating music from all the other cultural functions it shares (dancing, poetry, story-telling, and the tradition of cooking and eating around the fire while the community celebrates the exploits of the day). Additionally, “research has confirmed the brain’s link for words and music” (link), and that “to your brain, music is as enjoyable as sex” (link). Prior to the full-blow conversation is the musical duet of infant musical imitation, mimicking both tone, cadence, and emphasis with calls and gestures that combine to form an inter-generational jam session (link). Charles Darwin himself bemoaned his loss of appreciation for music and poetry and how immersion in abstract formulae stunted his intellectual curiosity:

My mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years… Now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry… I have also almost lost any taste for pictures or music… My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts…

If I had to live my life again I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week… The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature. The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, Norton 1993 (pp. 138-139)

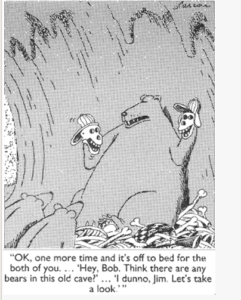

Academics and scientists tend to like the Far Side cartoons due to the odd ways the panels depict concepts. Here we have a bear telling the young ones about an exploit involving hunters. Although they are not sitting around a fire as pre-historic humans did while they cooked food (bears eat humans raw), other elements of story-telling around the fire are present in this depiction.

Academics and scientists tend to like the Far Side cartoons due to the odd ways the panels depict concepts. Here we have a bear telling the young ones about an exploit involving hunters. Although they are not sitting around a fire as pre-historic humans did while they cooked food (bears eat humans raw), other elements of story-telling around the fire are present in this depiction.

Two other significant features of very young infants have to do with imitation and turn-taking. From very early on, infants will imitate sticking the tongue out (the tongue is a prominent feature even for very young eyes). This shows that imitation is hard-wired into human neurology. The second is that young infants tend to become subdued when mother provides face-to-face stimulation, but when mother becomes subdued, the infant tends to become more active. This establishes a template for later conversations using words (Bruner, Garvey). Communicatively, the infant cries when distressed, but doesn’t yet have any control over how she cries, leaving it to mother to interpret the cause of distress.

So the infant is now regulated by the circadian rhythm, her bright-eyed smile has cemented the bond with her mother, and her eyes are developing so that she can focus on distant objects.

The double helix model is a bi-lateral model, and we will see bi-lateral developments associated with different stages and steps. At first, the infant is using her two ears to locate sources of sounds and her two eyes to start to see figures three-dimensionally. There is not yet any eye-hand or hand-hand coordination.

IMAGE COMPARISON

Five month old baby Lucas has just been baptized. At the reception afterwards, family and friends stand around the dinner table as Lucas is held up by his grandmother facing out to the audience. First, the nearest person to his right gains his attention by waving and smiling in the goofy way that people naturally do. Lucas’s face flutters as he makes the effort to focus, aided by the attention getting antics of the audience member. Once he succeeds at focussing, his eyes coordinate and get bright with the resultant smile. With implicit understanding, the rest of the audience falls into the game with the next person waving and smiling, his face fluttering until, bingo! the bright-eyed smile. He did this about a dozen times, ending with the person on his immediate left. A perfectly orchestrated developmental tour-de-force! [6/22/14] (Family Study, 2015 link)

To achieve the distance focus in the story above, the infant’s eyes must develop where the photoreceptors flow toward the center of the eye to create a fovea (Newsweek, Your Baby’s Brain, pg. 21). In the story above, Lucas must see the waving hand and the exaggerated smile before being able to target the eyes, make eye-contact, which then produces the bright-eyed smile.

So Lucas is able to connect one moment to the next moment, and so on, guided by the orchestrating adults. The other thing infants can do at this stage is to look at one thing, then look at another thing, and then look back at the first thing (Piaget). Infants are starting to map out their surrounding; location, location, location. Infants are also not completely immersed in the moment and have made their first time distinction: “now” and “not-now,” or “now” and “then.”

Looking at one thing, then another, and then back to the first thing also provides the developing infant her first method of self-regulation: when a stimulus becomes overwhelming, the infant can look away to avoid getting over-stimulated, and then when composed, can look back at the stimulating object (person, pet).

IMAGE RELATION

I was at Beers Books on Father’s Day with a friend. A father was pushing a pram through the aisles with Junior inside who was looking directly back at dad. Dad was obviously wanting some adult conversation and it soon became apparent why. Junior was looking out from under the open sun canopy, staring at dad without smiling. Dad reported that Junior is 8 months old and when asked he explained that Junior was not crawling or toddling yet because he was too large to get up enough effort, so he wanted to be pushed around to see the sights. Dad would put the canopy down hoping Junior would calm down and sleep, but as soon as Dad did so, Junior batted it or kicked it up so he could see. The canopy was in the way so Junior would dispose of it with a quick punch or kick motion. Dad referred to this as Junior’s “big trick.”

Here we see the kind of goal directed behavior that Piaget refers to as the stage of “secondary circular reactions.” Infants can now relate one object’s effect on another, such as when the infant uses a stick to move a toy. Socially, infants can get their mothers to do more specific things because the infant can vary the sound and the timing his cries while watching how mom responds. Volume can be adjusted to make sure mother can hear. Crying gets mixed in with fussing and other baby vocalizations.

These abilities show that the infant has gained a sense of three dimensional time, where something she has grabbed then gets used to move something else. “Grabbed” becomes past while “using” is the present in the anticipation of the movement of the other object. This involves eye-hand coordination (the infant will no longer grab one hand with the other as if the hand grabbed were not part of his body — just like baby cats will chase their own tails).

The infant’s abilities to locate familiar objects in familiar places also develops so that the infant can tell when a familiar object has been moved to an unusual place. She can also track the movement of objects and people, even when they are temporarily hidden.

But the infant still needs to have things at hand or for them to be brought to him — he is not yet crawling or toddling. In pursuit of distant or absent objects or people, the infant will come to realize his own agency. Frustrated that the world cannot always spoon feed him, he will start getting along and getting up to go get it himself. Eye-hand coordination prepares the baby to start locomotion, the bi-lateral skills of moving arms and legs in coordinated ways to get from one place to the other. Thus we come to agent formation, toddling, and vocalizations called “performatives” that go with request and demand gestures to enrich the infant’s communication with the caregiver.

Sphere of Agency

AGENT FORMATION

We now enter the “motor” phase of Piaget’s “sensori-motor operations.” In the double-helix model, this is when the infant becomes conscious and learns about the self as an agent, an entity able to act.

Agent formation is motivated by the infant’s boredom with what is at hand and interest in things distant or hidden. To get at these interesting but ungraspable things, people and experiences, the infant must either get to them herself or find communication means to enlist others to provide the desired proximity.

Infants not only explore what their bodies and their vocalizations can do, the two are often combined in communicative gestures called “performatives.” Technically speaking, a “performative” is a vocal ritual that accompanies gestures. Performatives develop in the context of caregiver “game formats” such as “peek-a-boo” and “what’s this?”, games that are often used by mothers well before the infant can actively engage in them (much less understand the referential meaning of lexical items). In this way, infants are primed by familiarity of game aspects such as turn-taking, ritual and imitation which lead up to the toddler’s eventual use of language (Bruner, 1983, chapter 3).

A well-documented development of this phase involves “stranger wariness” and “separation anxiety.” Both involve a realization that the mother is a separate agent who is necessary to help the infant manage distress. The infant becomes wary of strangers who act too familiar without the reassuring mediation of the mother, while at the same time the infant uses the mother as a safe base from which to explore the unfamiliar (assuming that healthy attachment has been established).

The infant’s major task of being aware of the self as an agent is learning to walk. For some children, toddler-hood begins with crawling, followed by attempts to get up on the feet. For those who by-pass crawling, thrusting the body up on the feet, assisted by either an adult or by leaning against something, is the “first step” to walking. The infant has yet to gain balance or to know how to put “one foot in front of the other,” so first steps are either maintained by adult “sky-hooks” (similar to how adults help children learn to balance a bicycle) or result in a bounce on the bum.

The infant’s awareness of others as agents has a similar primitive quality at this age. Before, when the infant wanted something, he just looked at it and whimpered. Now he whimpers and looks to mother for assistance. He realizes he has to appeal to her for the object to magically appear. He is also learning to go beyond eye-contact and find out what mother is looking at so as to establish mutual attention. Using the unique quality of the human eye, he can follow the direction of her gaze so that he can participate in what she is attending to. This ability to develop mutual attention is crucial for later language development. Bruner describes in detail the way mothers initiate infants into repetitive games such as “peek-a-boo” and “what’s this?” to provide a format in which children can increasingly participate (become “agents” in the game rather than just “experiencers” of the game; Bruner, pg. 56) to the point of creating their own lexical items.

AGENT COMPARISON

This stage has the character of repetition. Physically the toddler is toddling, taking one step at a time, using the arms not to help balance but to break a fall — hence the unsteady quality of the operation. The toddler’s uncertainty keeps her eyes on her feet rather than where she is going, and often needs props such as chairs or adults to keep standing and moving.

Communication also has a shaky two step quality. To get help from mother, the toddler is aware that he needs to both get her attention and specify what he wants with conventionalized gestures and vocalizations. But these two functions are not well coordinated as yet. And while trying to figure out what mother is focusing on, if he is not successful in following her gaze the first time, he will return to her face to try to follow her gaze a second time (Bruner, pg. 74).

AGENT RELATION

If the infant’s sense of agency is first primitive and then erratic, it now becomes coordinated and organized. The toddler becomes a walker when she uses her arms for counter-balancing the legs rather than shielding an impending fall. And she can now coordinate gestures and vocalizations to better get mom’s attention where she wants it. And in ritualized games like “peek-a-boo,” the infant now can be a full participant with inter-changeable roles, everything short of using words symbolically (vocalizations are still imitations of sounds used ritually in the game sequence rather than symbolic referents).

The “relation” quality of this stage can be seen clearly in what the literature calls “give-and-take reciprocity.” Children learn that roles are reversible and reciprocal such as when one takes what someone has given and then turns around to give what was taken (going from being a taker to a possessor to a giver). Sometimes a gift is a material benefit and sometimes it is a symbolic act where the giving is the focus more than the gift itself. So children are initiated into give-and-take games such as rolling a ball back and forth — the object is not to keep the ball, but to send it back to its previous possessor. Here is how an extended family member or family friend can engage the 11 to 15 month old:

First, you want to make sure Junior understands that Uncle is a trusted family member and won’t over-stimulate him. Junior then sees that Uncle is delighted with a ball as he sits on the floor, creating a desire in Junior to get the ball himself. Uncle rolls the ball to Junior who then picks it up. Well, it’s just a boring ball, so now what? Well, Uncle seems very interested in getting the ball back. If Junior doesn’t catch on yet, Uncle may need to gently dislodge the ball from Junior’s grasp. At the point at which Junior might get upset, he finds the ball immediately rolling back to him. A little prompting from Uncle may still be necessary, but if Junior is ready to learn, he will find that “playing ball” is more interesting than “having ball.”

During this time parents are typically “bathing” their infants in language. The infant’s developed sense of agency is primed to take on words as communication tools once these ritualized “proto-conversations” are established. Once the infant makes the symbolic connection, she is no longer an “en-fant” (French meaning “without speech”), and has been drawn in to the world as a symbolic realm.