Lawrence Kohlberg/ Karen Armstrong / Ken Wilber

Stephen Hawking/ Thich Nhat Hanh:

Adverse Health Conditions, Responses and Outcomes

“My Body is a Cage” (by Arcade Fire, covered by Peter Gabriel, Scratch My Back 2010)

“My Body Ain’t My Buddy Any More” (Mary Holmes, circa 2000, artist and art historian, on her health at the end of her life when her fingers were cramped with severe arthritis.)

My writings have touched on spirit/body issues in the past, and this one will extend those views into new territory. Many of my friends and heroes have dealt with people who are both influential but difficult, and in this article I intend to come up with some guidelines on dealing with inspirational but difficult friends or associates when they are experiencing debilitating health problems. The question posed throughout this article is: What happens to the ego under debilitating physical conditions? It is hard for the ego to gain positive benefit under dire medical circumstances, but how does one maintain a healthy ego without undue expansion or contraction?

Lawrence Kohlberg and Karen Armstrong

In my paper on Kohlberg’s suicide (link), it becomes evident that Kohlberg’s abdominal parasite that was progressively deteriorating his health and peace of mind pulled him off the spiritual path that he was starting to travel with his companions F. Clark Power and James Fowler. His personality changed from a hard-driving but open-minded one to a close-minded and obsessed one as he increasingly alienated his family, friends and colleagues. Although married and with two children, and affianced at the end of his life, the only family member to speak at his memorial service was his older sister, who chronicled the changes Kohlberg went through in his life. We can see from Kohlberg’s example that spiritual development, while not “soft, hypothetical and metaphorical” as Kohlberg deemed it at the end of his life, but none-the-less, fragile (as is life, and our very planet as seen from a cosmic perspective).

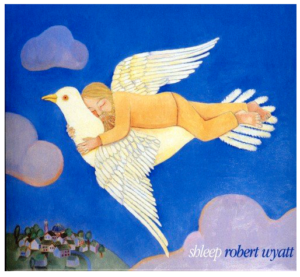

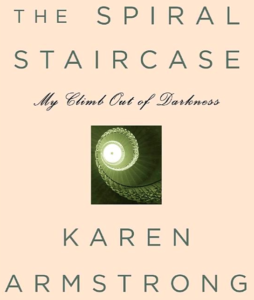

Let us now look at the issue of spirituality and chronic disease from a different perspective, the one presented by religion writer Karen Armstrong in her autobiographical book, The Spiral Staircase: My Climb out of Darkness (Knopf, 2004).

In short, Karen’s story is that at age 16 she was determined (against her parents’ wishes) to enter a convent and gain the spiritual consolation that comes with a life dedicated to prayer. This she did, but after 6 years she still had not experienced the consolation that the other sisters found. She ended up leaving the convent and attempted to get established as a professor of English literature. Although her university plans got dashed in a tragic way, she gained some notoriety for being a critic of the Church (See her previous autobiographical books, The Narrow Gate, 1981 and Beginning the World (1983)). The tone of those works was admittedly bitter, and Karen rejected Beginning the World as her worst work by the time she was ready to write The Spiral Staircase.

What happened is that Karen discovered that she was suffering from undiagnosed epilepsy. This neurological disease was making her incapable of experiencing the bliss that comes with a disciplined prayer life. When at university, it also prevented her from enjoying the parties with loud music and strobe lights, or forming an intimate relationship:

At the time when most people are supposed to find a mate, I was engaged in a solitary battle with an undiagnosed illness, and locked in a private hell. If you cannot trust the integrity of your own mind, you cannot fall in love, and neither can anybody fall in love with you. (pg. 190)

It was only after she got properly diagnosed and her medications were stabilized that she could see out of the darkness of her spiral staircase.

It is fascinating to read her account of how she functioned and the glimpses she had of getting beyond her malady. Her emotional detachment along with her formidable intellect made her a very concise writer, but her inability to resonate with others left her isolated. This dilemma became clear during her preparations for her doctoral thesis orals:

All of my written answers had been carefully contrived. During the long weeks of revision, I had prepared essays that could be adapted to meet almost any contingency. They were my usual Gothic cathedral creations, intricate edifices of other people’s thoughts. But now I knew that there was no chance I would be able to think on my feet in the way that would be expected of me. (pg. 76)

The only two areas of art that resonated with Karen Armstrong were music (particularly Beethoven’s late string quartets) and poetry, especially T.S. Eliot who also suffered from epilepsy. She didn’t know why or how Eliot’s poetry appealed to her until she was properly diagnosed and treated. It was then that she had her “meeting of minds” with Eliot and she gained the confidence to explore the tricky and fascinating world of religious history and comparative religions.

Differences between Kohlberg and Armstrong

While Kohlberg’s malady was worsening, his work life became increasingly frantic while his personal life became more stunted. He apparently did not confide in any of his family or friends about the depth of his depression or his suicidality (Dr. Susanne Cook-Greuter informs me that he was engaged to be re-married when he committed suicide). He probably considered it his moral duty to keep these problems from his loved ones — whether this was stoic heroism or self-deception I could only speculate.

While Armstrong’s malady was worsening, she was striving to achieve the spiritual intimacy that comes with a life of prayer. When she failed, she sought other means to settle her soul. After receiving adequate treatment, she was able to reconcile her emotions and establish herself as a unique and respected voice in the field of world religions.

Chronic physical and psychic pain presents a challenge to achieving and maintaining the spiritual attitude of gratefulness. It challenges our desire for control and our sense of belonging in the world. Suffering is not a virtue if it can be avoided without harming others, but a life spent avoiding suffering rejects the fulness of life and lacks the experience that forms the basis of gratitude. Chronic pain can cripple our budding spirituality, but spirituality can also protect us from allowing chronic pain to cast us into despair.

Medical trials using psychedelics have cast an interesting light on this question:

The existing pharmacological and psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in patients with cancer and other terminal illnesses are currently very limited. Epidemiological data show that spirituality has a protective effect on psychological response to serious illness. We also know that spiritual well-being is negatively correlated with hopelessness in cancer patients, and that cancer patients are interested in addressing issues of spirituality.

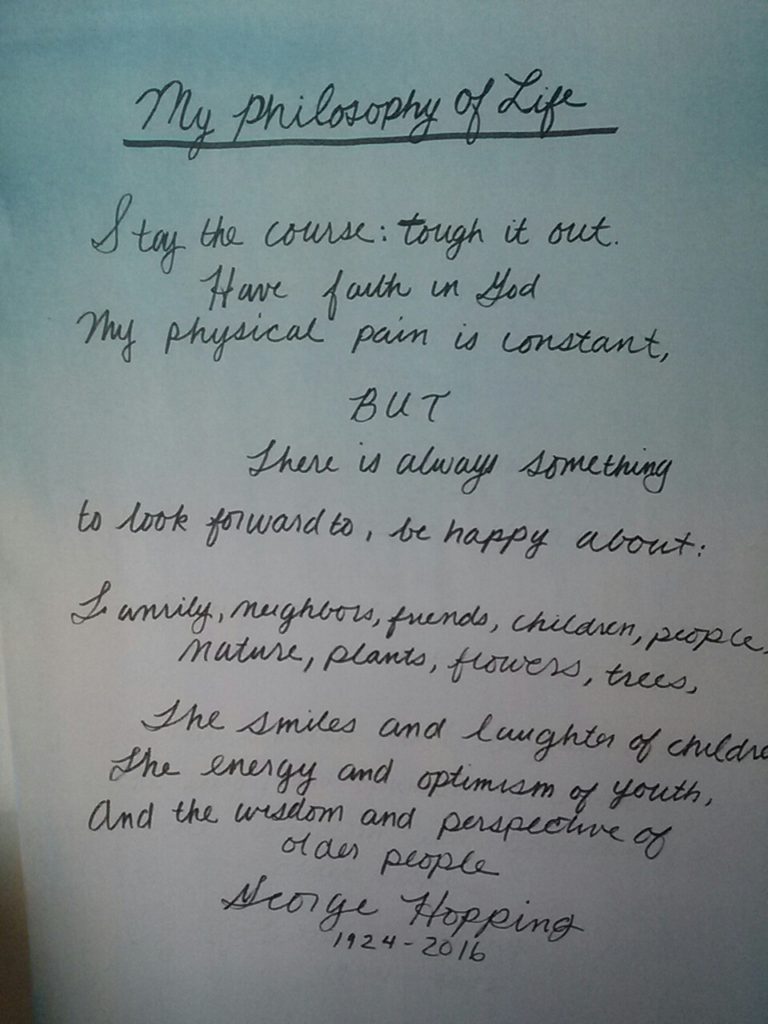

[An Interview with Roland Griffiths, in Frontiers of Psychedelic Consciousness by David Jay Brown (Park Street Press, 2015) pg. 252.]In recent years I have become more aware of the many people who experience crippling health problems shortly after they retire. I attribute much of this to the fact that while we are in the “rat-race”, we tend to ignore or underestimate mounting physical problems. Having chronic pain can actually help with this, since men particularly tend to avoid doctors and medical care, but those with chronic pain are dependent on getting good care. My oldest niece’s grandfather had severe chronic back pain throughout his life, and he wrote what amounts to a credo of gratitude for chronic pain victims:

So even if you can’t find your “happy place” in all circumstances, try to maintain your “happy pace” so that you can come out the other side of the tedium of everyday life grateful, well rested, with steady breathing and ready to laugh with others. [This can be hard to do if one is limited to “motivated reasoning,” which is inflexible to changing circumstances. To the extent that George Hopping was limited by “motivated reasoning”, he had a good set of values to hold to, as can be seen in his life credo above (more the gentle Franciscan than the rigid Calvinist, even though he had the iron will of a Calvinist). For more on this, see the “Character Comparison” section of the Research Findings, link here.]

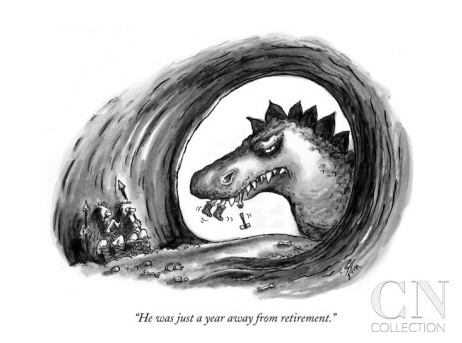

A Far Side Comic Frame depicts the tragedy of losing one’s life/health just as one is about to gain the reward of labor:

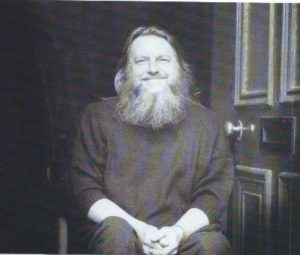

Ken Wilber

I have now added a section on Ken Wilber’s adverse medical condition, his responses and outcomes, to complement this article.

Ken Wilber contracted a little understood malady in the 1980’s (RNase Enzyme Deficiency Disease) which renders the victim bed-ridden for up to years at a time, with difficulty even breathing. Wilber’s meditation and writing skills have served him well over the years to help him manage the malady, but it can be so severe that at times he could only open one eye at a time (one eye for near-sight and the other for far-sight). Wilber managed to avoid treatments that turned out to be counter-productive, and his celebrity status probably helped the medical profession better understand the malady (the cause is still unknown, but assumed to be an environmental toxin — for his explanation in 2012, see this 10 min. video). Unfortunately in 2006, Wilber published on his website an extensive criticism of his critics that is laced with vile language and gratuitous insults. This, and his questionable endorsements of spiritual “leaders” who have come under scrutiny for various abuses in recent years, has caused a number of his followers to distance themselves from him (see “The Rise and Fall of Ken Wilber” by Mark Manson, which can be found on google).

I am aware that profanity and tirades can provide short-term relief from pain, but it is one thing to express such things in private or with confidantes, it is another thing to write these thoughts down, it is yet another thing to post them in public, and yet another to keep them posted for over a decade. And finally, to keep referencing back to themes and images from that screed (e.g. his praise for the “enlightened” rudeness of his identified “spiritual leaders”) leaves me feeling between saddened and sickened.

Although Kohlberg’s situation resolved negatively and Armstrong’s positively, Wilber’s spiritual status appears to be currently in danger if he does not distance himself from his glib communication style and abusive associates. For more on Wilber’s errant ideas, click here.

So there it is. My hope is that Ken Wilber will regain his serenity, take down his offensive screed, and disassociate from abusive leaders he has endorsed. (Deepak Chopra has done so in one instance where Wilber continues to ignore or defy pleas to disassociate himself. The problem is, devotees continue to flock to these questionable leaders based on Wilber’s endorsements.) Here we can insert a moment of silence with prayers for Ken Wilber’s soul.

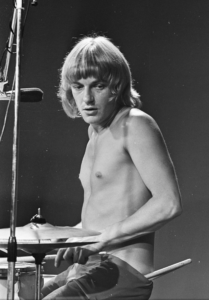

I will end with something of a (crippled) lullaby written by Robert Wyatt who was the drummer for Soft Machine before he had a terrible accident in 1973 which paralyzed him from the waist down. Even though his days of rock drumming were over, he continued with his musical friends to develop whimsical music and make concert appearances with leading musicians (Pink Floyd did benefit concerts to aide his healthcare). Here, in a song he recorded with Brian Eno, he describes his chronic struggle with insomnia on a record called “Shleep” (1987):

ROBERT WYATT

“Heaps Of Sheeps”

I realised my fists were clenched,

I stretched my fingers to relax.

Still not sleeping, I tried counting sheep.

One by one,

They leapt across the fence

Constructed for them,

Right to left,

Across the fence I had constructed.

Having jumped,

They refused further direction.

Each sheep, where it landed,

Refusing to exit, remained.

(Creating a vast writhing heap

Growing fast on the left).

Try as I might,

I could not stop them entering

Once again.

Try as they might,

Not one could leave the stage.

I realised my fists were clenched.

I stretched my fingers.

Each sheep where it landed,

Refusing to exit, remained.

(Creating a vast writhing heap

Growing quickly on one side).

Try as they might,

Not one could leave the stage,

Try as I might,

I could not stop them entering,

Once again.

No longer daring to close my eyes,

Still not sleeping.

I realised my goose was cooked

I wandered shipshaped on the shore.

Now if that isn’t whimsical acceptance of chronic discomfort, well, I would like to hear of more examples (actually, a good one is Michael J. Fox, who now uses the involuntary muscle movements of multiple-sclerosis as part of his comic presentation-of-self). Music, even if rather discordant, adds good vibrations to an often unsettling life. As an art historian recently said: “Anything that adds pleasure increases motivation.” So without music (Steven Pinker), chronic pain in life would be even more of a bitch (survival of the more harmonious). Similar to how cats purr out of contentment or to ease discomfort (such as healing broken bones), we too can humm to add enjoyment or ease the pains of life (such as nasty voices in the head, if one has them). So I end with the value of music for good vibrations and harmonious relationships.

Stephen Hawking

OK, I lied, I am going to do one more. Stephen Hawking is an astrophysicist who has a rare early-onset, slow-progressing form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that has gradually paralysed him over the decades. He has managed to control a wheelchair and voice machinery to the point of dominating the astrophysics world for years on end. He messed with other people’s research to the point that they pushed back, and he recently lost two significant bets. The first was with Leonard Susskind, related in Susskind’s book The Black Hole War (2008), where Susskind shows how he helped prove to Hawking’s satisfaction that information is not lost in black holes (if it was, we would never have a universe again once this one comes to an end). The second bet was on the “Higgs Boson”, which was statistically verified to strict scientific standards from the Hadron Collider in 2012 (see Lisa Randall, The Higgs Discovery (2012).

Hawking is an odd duck in this mix. His biography has been put on the silver screen by the able hands of Errol Morris (A Brief History of Time, 1991), and some of his most brilliant moments came out of meetings at the mansion of EST founder Werner Ehrhardt (keep me out of there!). He has consistently used his prodigious mathematical imagination and his frisky wheelchair to bewilder and upset his colleagues, while having the humility to pay out more than one bet when the evidence proves him wrong. How far out into the universe will his wheelchair go, only Major Tom knows! But beware, he is a sourpuss, which could possibly be related to his crippled body. Why else would he characterize the whole human race as “scum”:

The human race is just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet, orbiting around a very average star in the outer suburb of one among a hundred billion galaxies.

Well, it turns out that the sun isn’t an average star (it rotates over 7 degrees off perpendicular to the solar system plane, and it doesn’t have a large gas planet like Jupiter orbiting inside Mercury’s orbit like most average stars do), and there are examples of chemical scum that are a lot less clean and organized than we are (although our pollution is proving him tragically correct). But if I had his physical problems, I would probably be less grateful as well.

Stephen Hawking may be a sourpuss, must not a bitter sourpuss, which is perhaps an example that Ken Wilber could benefit from. In contrast, Ken Wilber’s sense of humor has become sick and turned to rot in its wild west allegory.

One more musical analogy: David Bowie died of liver cancer, but while he was living out his last months, he was incredibly productive and creative. His parting video, Lazarus, shows him as a truly unique star worthy of the name Dark Star (which is the original name for a black hole). Ground control to Major Tom. As for rot, his last email to Brian Eno was “Nothing we have done will turn to rot.” Now there is some gratitude at the end!