CULTURAL REALM

CULTURE FORMATION

There is little to no controversy over the character of “concrete operations” as they normally develop in the 7 to 12 year-old age range. The changes that normally ensue around 7 years old are far-ranging and well documented. The changes generally involve hierarchical thinking and organized behavior sequences. Thus, for instance, children can now copy Greenfield’s mobile tree using the cross sticks as hierarchical organizers of the vertical sticks. Over the period of a few years they find increasingly more efficient ways of constructing the mobile. This is similar to children’s developing understanding of social organizations such as sports teams — they are directed by a “superior” coach who delegates on field strategies to an on-field leader (e.g. quarterback in football, center in basketball) who coordinates the moves of the other team positions.

Among all these changes that develop with the onset of “concrete operations” (which I think of as more cultural practice identification), I will be focussing on one change that seems to me to be central to the school-aged child’s social and emotional functioning: the understanding of, and the ability to, promise something. The realization of the meaning of promising is at the heart of children’s role development: to be a parent, a teacher, a student, an older sibling, a team member, etc., one understands that there are certain expectations that go with the role, and that agreeing to play a role is not just a matter of agreement with an idea — it is a promise to do the things that fulfill the role. And if one fails these expectations, others can be expected to be disappointed.

In her book The Acquisition of Syntax in Children from 5 to 10 (1969, MIT), Carol Chomsky conducts some enlightening studies on children’s understanding of “promise” (pp. 32-41). When asked to depict sentences involving “told” and “promise,” she found a sharp difference between the understanding of 5 year-olds and 8 year-olds. For instance, if the sentences were “John told Mary to go to the store” and “John promised Mary to go to the store,” the 8 year-olds had Mary go to the store in the first sentence, and they had John go to the store in the second. Whereas the 5 year-olds had Mary go to the store with both sentences, not understanding that a promise commits the promiser’s own actions in the future, not somebody else’s.

In this sense a role sets certain expectations that the role-player promise to do the culturally prescribed performances attached to that role. So let’s have some fun and explore how children take on the role of “joke-teller.”

Paul McGhee explored this question in his article Development of Children’s Ability Create the Joking Relationship (Child Development, 1974, 45, 552-556). In it he concluded that children can create a joking relationship along with concrete operations at the age of 7. Too bad his examples are kind of lame, but we can fix that! Following are some examples from holiday family gatherings:

For many years running, we had Thanksgiving with our extended family, including an adult nephew, his wife, and their three children: Ashlyn, born in 2005, Connor; born in 2007; and Lucas, born in 2014. Their mother is an elementary school teacher and their father an engineer (with good social skills). The mother and I would typically talk about child development, including observations of the children’s current interactions as well as various ploys to elicit interactional sequences (such as rolling a ball back and forth with infants getting close to speech). So this was a familiar and friendly setting for the adults and children. The parents are attentive to their children, but do not let them interrupt adult conversations, so the children develop various acceptable ploys to enter a conversation without interrupting it.

During Thanksgiving of 2012, the adults were sitting in the living room with a coffee table surrounded by a couch and various chairs. Ashlyn (now 7 1/2 years old) and her younger brother Connor (who just turned 5) came into the room crawling, Ashlyn in front and Connor following. They went around the perimeter of the room with Ashlyn pretending they were hiding by crawling under chairs between the chair legs. Ashlyn knew she could be seen but was making a good pretense of hiding; Connor was just along for the ride, knowing that following his sister generally led to fun.

Ashlyn ended up slithering on the couch beside her mother. I was on the other side of mom and told her the story of Jason and the hide-and-seek game (above), using verbal dramatic effects (e.g. cupping my hands mega-phone style to reenact “He’s In The Bathroom!”) At the end of the story, mom says to Ashlyn, “That was a funny story, Ashlyn, wasn’t it?” Given what Ashlyn did later, it is evident that Ashlyn got the idea that the name of the game in this setting was to tell funny stories, which to her translated as telling jokes.

So in the wake of the meal, while she still has a full audience, Ashlyn stands up and says that she has some jokes to tell. There were four of them along the lines of “What kind of ship never sinks?” “What kind?” “Friendship!” and “What kind of weather do mice hate?” “What kind?” “When it rains cats and dogs!” There was no theme to the jokes — she told them as she remembered them.

After this, the father told me that Connor didn’t understand that with a joke, when you ask a funny question you are expected to supply a funny answer — he would just ask the funny question and expect the adult to supply a funny answer. The social convention is that when you set yourself up in the role of joke teller, you are promising to deliver the punch-line.

This theme continued for the next two years of Thanksgivings. For 2013, Ashlyn will be featured in the next section. For 2014, Connor had just turned seven, so it was time to check in with his joke-teller status.

Towards the end of the visit, I asked Connor if he had heard any jokes recently. While he hesitated thinking, Ashlyn was ready to tell a joke, but I held up my hand to stop her while I focussed on Ryan, waiting for his response. Finally he said: “What do you use to drive the cows home?” “What, Connor?” “A cow-dillac!” To reinforce his knowledge of jokes, his mother then prompted him to tell the joke he brought home from school recently: “How do you spell I-CUP?” Being game, I immediately blurted out: “I see you pee!” which brought giggles all around. Many people obviously fall for this, but the “real” answer is eye-cup, as in the device used to wash out your eyes. Alas! But it did establish Connor as a bona-fide joke teller.

CULTURE COMPARISON

2013 Ashlyn smuggles a joke book:

Ashlyn planned to do a stand-up comedy routine armed with a joke book written for children her age. Apparently her parents told her not to bring the book, but she smuggled it in anyway. After the meal, while people were standing around talking before they started to leave, Ashlyn pulled out her joke book to try it out on her small audience, myself and her father. After shoe-horning in a couple of jokes she read from the book (not that good), her father declared the last one to be a “groaner” (which everyone understood to mean “lame”). This was the signal to break up the audience, and father went one direction and I went another. Never one to be discouraged by a mild rebuff, Ashlyn went on the practice her other, more successful, conversational ploys.

That year Ashlyn tried to extend her joke “performances” into an assembled routine of jokes as they appeared in the joke book. Although there is a focus on augmenting the routine one joke at a time, there is no reciprocity that would make it a stand-up routine where one joke builds on another, where jokes refer back on themselves and where the built-up structure can come tumbling down like a house of cards (to the merriment of spectators who can view the travesty at a safe distance). Joking partnerships can be so motivating that two years later (11/24/16), after not seeing me in the intervening two years, her younger brother Connor (now nine) told me he had a joke for me as his greeting upon first seeing me:

Q – “What do you call a key that doesn’t work?” A – “A donkey [don’t key]!” When I first answered his riddle with “don’t key” it didn’t sound enough like “donkey” for Connor to understand. Unfortunately for Connor, his older sister Ashlyn, now eleven, pointed out to him that my guess of “don’t-key” was correct even though it didn’t sound enough like “donkey” for him to notice. Undeterred, Connor went on to include variations such as “turkey” and “monkey.” I then explained to him that a “monk-key” was used by a monk to enter the abbey. Lost on him but not on his sister who will continue to indoctrinate him into the world of joking partnerships).

However diversified and inter-related the elements of the performance become, at each stage of the way the school-age child is measuring his and others’ performances by a concrete standard which the performance strives to achieve. The involves inductive reasoning, generalizing a specific performance as a standard to measure performances of the same type (the “right” way to do it). Children 7 to 12 years old are encouraged and interested in “getting good at something” (Erikson’s challenge of Industry vs. Inferiority), both to make their parents proud, and to make themselves interesting to like-minded friends.

But as the above story of Ashlyn shows, it is not just doing things well, it is doing them when people expect them. It is hard to keep a promise if one forgets it at the relevant time. To be successful at this stage, children need to develop ways to remind themselves about their responsibilities. Children at the previous stage are inconsistent about this: they can find a way to remember one thing, but can’t generalize this method to similar situations, nor articulate how they did it. Eight-year-olds can do this, and parents can expect them to keep on track without needing to be reminded (see Carolyn Hoyt, “Developing Your Child’s Memory,” from Parenting.com). Consider this day-long performance by 8-year-old Ashlyn on the day of her First Communion:

It was the day of Ashlyn’s First Communion. She had a series of tasks to accomplish that day: get dressed and ready, go with the family to the church, understand and complete her role as a first communicant, sitting with the other children and following the priest’s directions with the other first communicants and the other children attending. At the same time she was responsible as older sister to make sure her younger brother followed directions as well. After the priest’s talk with the children, Ashlyn’s family was the chosen family to bring the gifts before the altar, and this involved getting on-the-spot instructions about how to carry the gift, when to start the promenade, the pacing and spacing of the gift-bearers, and the custom for handing the gifts to the priest for his blessing. Last but not least, she was the hostess and guest of honor at the family reception afterward, greeting new guests as they arrived, making sure people had drinks and food, and generally circulating so as to stimulate conversation amongst the guests. All flawlessly performed: hurray to Ashlyn! [5/5/13]

Children are certainly relieved when they remember the things that are expected of them, but their greater interest tends to focus on getting recognition for a good performance. A good example of “getting good” at something comes from the life of multi-grammy award winning music producer Daniel Lanois. He was not given a musical instrument at a young age as many musicians were, but instead made a choice at age nine to pursue music in his own way:

Interview: Daniel Lanois

The Brian Eno, U2 and Harold Budd collaborator talks about his remarkable career

By Frosty October 14, 2015

Red Bull Music Academy Daily

How did you get introduced to playing and recording music?

When I was nine-years old, my mom would give me a dollar a week to go to the movies. I would walk a couple of miles to the movie house and enjoy my Saturday cinema – but, on this one Saturday, I saw a video in a music store window for this little, plastic recorder. It cost a dollar. On that day, I didn’t go to the cinema. I bought the recorder and played that thing until I made everyone in the building go crazy. I started inventing melodies and then my own annotation system, too, because I didn’t know how to read music. That was the beginning of composition for me. I’ve been a dedicated note-keeper ever since.

When Lanois’ production mentor, Brian Eno, heard this story, he reflected (as documented in Lanois’ movie Here Is What Is) that Lanois’ spontaneous decision to buy the recorder at nine years old changed his whole life trajectory, and those of many around him. Watching this interaction between Lanois and Eno reinforces the importance of friendship in cultural development.

In the Cultural Realm, friendship is a role involving expectations and promises, the sharing of interests, likes, dislikes, and (danger zone!) friends. As Selman (1976, 1981) has found, ideas of friendship go hand-in-hand with ways of dealing with conflicts and understanding the perspectives of others. I find particularly interesting Selman’s findings on children’s understanding of “apologies.” But before investigating the details of this, let’s cover some background on the developments Selman finds, starting from the “friend as playmate” orientation during the Sphere of Subjectivity, through the three levels involved in the Cultural Realm.

Selman Friendship Concepts of Children (1981, pp. 250-251) in relation to Double-Helix Model Patterns:

Sphere of Subjectivity

Stage 0: Momentary physicalistic playmates. Conceptions of friendship relations are based on thinking which focuses upon propinquity and proximity (i.e., physicalistic parameters) to the exclusion of others. A close friend is someone who lives close by and with whom the self happens to be playing with at the moment. Friendship is more accurately playmateship. Issues such as jealousy or the intrusion of a third party into a play situation are constructed by the chid at Stage 0 as specific fights over specific toys or space rather than as conflicts which involve personal feelings or inter-personal affection.

Culture Formation

Stage 1: One-Way Assistance. Friendship conceptions are one-way in the sense that a friend is seen as important because he or she performs specific activities that the self wants accomplished. In other words, one person’s attitude is unreflectingly set up as a standard, the “friend’s” actions must match the standard thus formulated. A close frieind is someone with more than Stage 0 demographic credentials; a close friend is someone who is known better than other persons. “Knowing” means accurate knowledge of other’s likes and dislikes.

Culture Comparison

Stage 2: Fair-weather cooperation. The advance of Stage 2 friendships over the previous stages is based on the new awareness of interpersonal perspectives as reciprocal. The two-way nature of friendships is exemplified by concerns for coordinating and approximating, through adjustment by both self and other, the specific likes and dislikes of self and other, rather than matching one person’s actions to the other’s fixed standard of expectation. The limitation of this stage is the discontinuity of these reciprocal expectations. Friendship at Stage 2 is fair-weather — specific arguments are seen as severing the relationship although both parties may still have affection for one another inside. The coordination of attitudes at the moments defines the relation. No underlying continuity is seen to exist that can maintain the relation during the period of conflict or adjustment.

Culture Relation

Stage 3: Intimate and mutually shared relationships. At Stage 3 there is the awareness of both a continuity of relation and affective bonding between close friends. The importance of friendship does not rest only upon the fact that the self is bored or lonely; at Stage 3, friendships are seen as a basic means of developing mutual intimacy and mutual support; friends share personal problems. The occurrence of conflicts between friends does not mean the suspension of the relationship, because the underlying continuity between partners is seen as a means of transcending foul-weather incidents. The limitations of Stage 3 conceptions derive from the overemphasis of the two-person clique and the possessiveness that arises out of the realization that close relations are difficult to form and to maintain.

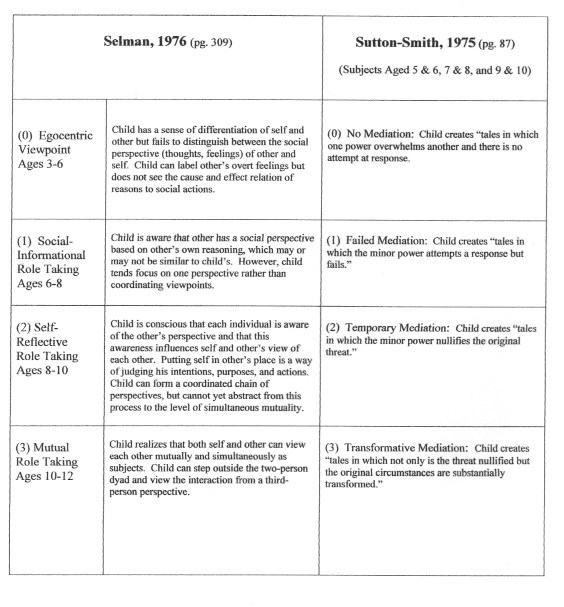

The chart below organizes Selman’s Role Taking Stages (1976) in relation to Sutton Smith’s studies of children’s creations of stories (chart created by this author):

During the Sphere of Subjectivity the child fails to understand that people have perspectives that may differ, and the stories they create have conflicts where there is no attempted solutions. With Culture Formation, children understand that people have perspectives and will provide one-way assistance in a conflict, while the stories they create have an attempted solution that is not sufficient to resolve the conflict. With Culture Comparison, children can start comparing perspectives and providing “fair-weather” assistance when the conflict to not too serious or complicated, while the stories they create involve responses that resolve the immediate threat. With Culture Relation, children can understand the mutuality of perspectives from a “third-person” viewpoint and start to “talk things out” when conflicts are more serious or complex, while the stories they create involve transforming the circumstances of the conflict as well as eliminating the immediate threat.

Since the role of a friend involves keeping promises, any failure to keep a promise presents a role conflict that threatens to end the friendship if not rectified. Younger children are typically told to “say you’re sorry” when they create a conflict, but with Culture Formation children understand that an apology is an important means for restoring the relationship. Children first register “sorry” or some other gesture to make things better as an important step, but they soon come to realize that sincere apologies involve more than saying “sorry,” as the following interaction demonstrates:

I was working for a Family Service Agency, providing consultation for school personnel, running multi-family groups, and student-assistance activities at various elementary schools. At one school where I provided multiple services, I was outside a classroom when recess was ending. As I walked up to the room two students were arguing — a smaller boy was confronting a large 10 year-old girl about some bullying behavior. Just as I walked up, the girl said loudly “I SAID I WAS SORRY!!” I said to the boy, “But sorry is as sorry does.” The jaws of both the boy and the girl literally dropped, and the girl walked off.

As Selman says, the child at Stage 2 (Culture Comparison) is concerned that “one must mean what one says” (1981, pg. 260). In terms of perspective-taking, Selman would say that the girl needs to “be aware that another self can judge one’s beliefs and intentions as well as one’s actions” (pg. 260), a point that was not lost on the boy. And he saw that she got the message too.

CULTURE RELATION

The third stage in any realm or sphere is always the more organized, and Culture Relation is no different as characterized here by Robert Kegan (1985, pg. 197):

In bringing impulses and perceptions under his or her own regulation, the child creates a self that is distinct and in business for itself; in its fullest flush of confidence this is the bike-riding, money-managing, card-trading, wristwatch-wearing, pack-running, code-cracking, coin-collecting, self-waking, puzzle-solving 9- or 10-year-old known to us all.

Anyone remember this “Game of 15”? I got good at it when I was 10 years old, just when I was memorizing the times tables.

The nine to twelve year old youngster who has gotten really good at something is often at the top of their game, particularly for concrete performances such as gymnastics, spelling bees, and multiplication tables. Kegan’s description reflects the typical boy at this age, but girls have similar, often more social performances they like to show off, such as the culturally ubiquitous hand-clapping games (e.g. “Miss Mary Mack”). Youngsters generally love getting accolades when they can tell that they “stuck it” with their performance. A good description of the high feeling associated with a recognized accomplishment comes from an interview with actress Helen Mirren (1975 with Michael Parkinson, link, be fore-warned, the interviewer is very sexist):

I first discovered I wanted to be an actress when I was at primary school. I played the Virgin Mary — why do they laugh? — I don’t understand. And I was really rather good — people said I was good anyway. And I got that terrific feeling of being good at something and other people recognizing that. I remember very clearly that feeling.

[Helen Mirren played this role when she was 6 years-old. The part had no lines but had a stunning costume. By the time she left primary school at 11 years-old, she had played the leading role in Hansel and Gretel, with so many lines that the script was bound in a book. She tried to get out of the ordeal, but her mother wouldn’t let her. (see In the Frame: My Life in Words and Pictures by Helen Mirren, Atria Books 2008, pp. 47-8)]For a wonderful example of a musical child prodigy showing off her bi-lateral drumming skills in a performance that stunned Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin, watch this video of an 8 year old Japanese girl here.

This is all great stuff, so what could go wrong? Let’s talk about narcissism.

This age group has strong inductive powers, but not yet the deductive powers that involve defining abstract principles and applying them to specific situations. Therefore, a “good” performance is one that meets the standard of excellence whether or not it is helpful to others or beneficial to humanity. Hitler Youth were very disciplined, but had no conscience about the misery and evil their actions were creating. Children who are attractive and talented are in danger of becoming smug, showing off at others’ expense. Narcissists become used to getting their way, and are generally very charming while they do. But when they don’t, watch out! In this regard, the story of Tonya Harding, the famous figure skater who “landed her first triple lutz at age 12” (Wikipedia), comes to mind: when her place at the pinnacle was challenged by Nancy Kerrigan, Harding had her knee-capped in 1994 so she couldn’t compete against Harding in the U.S. Figure Skating Championships. Unfortunately, her life since 1994 has not evidenced much of what could be called “soul searching,” which begins when we get thrown back on ourselves and start to explore Character Formation.

Sphere of Character

CHARACTER FORMATION

“The heart has its reasons, of which reason knows nothing.” Blaise Pascal

“Confusion will be my epitaph, As I crawl a cracked and broken path. If we make it, we can all sit back and laugh. But I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying, Yes I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying.” King Crimson, “Epitaph”, The Court of the Crimson King, 1969.

Before going into the heady sphere of character development, let us bid farewell to our “research subject” Ashlyn, who at 11 years old (11/24/16) has joined the world of “elders” who help the younger learn and become successful in social life:

At my last encounter with Connor, who eagerly greeted me with “I got a joke for you!”, Ashlyn played the concerned observer who was the first to point out to him that I had actually got the punchline right (see above, under Culture Comparison). Along the same lines, during Thanksgiving dinner, she actively observed when Connor started to go into too much detail about a time he got sick and his mother, with that thin edge to her always friendly voice, warned him to change the subject. On our side of the table, I cast a glance at Ashlyn, saying “too much information,” to which her smile and wink communicated her understanding of the “wisdom of the elders.”

Thus, Ashlyn has earned the privacy afforded responsible adolescents, and her further role will be as a research assistant (with her mother and father) rather than a research subject.

In this model, as in many others, character development involves balancing the seemingly conflicting demands of justice and caring, self and others, ethical disciplines and indulgences. For a snapshot of how we got here, let us consider the testimony of an unlikely source, the 18th century philosopher and economist Adam Smith:

According to Smith’s theory, we begin developing our moral instincts — our “sentiments” — by sympathizing with the pleasures and pains of others through imagining what we would feel in their place. As we become aware of these sentiments, we recognize that we approve of a man’s behavior when his behavior accords with with the emotions we imagine we would feel were we in his place. When his actions and our imaginations coincide, we approve of, or sympathize with, his actions. We then observe how others see our own behavior. We learn which behaviors elicit sympathetic responses in others — which of our actions seem to others to be appropriate to the circumstances — and we adjust our own behavior, so as to cultivate praise from others. Finally, we internalize the mechanism. We develop our own “impartial spectator” inside us. We no longer seek the praise of others; instead, we seek to be praiseworthy in the eyes of our own internal, impartial spectator. Only at this point are we equipped to become fully functioning members of society.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments, 1759, by Adam Smith, reviewed by Edward D. Kleinbard in Commonweal, Dec. 4, 2015, pg. 33.

Adam Smith was the author of The Wealth of Nations, 1776, which has been mis-understood as supporting “dog-eat-dog”, un-regulated capitalism. But Smith considered his “Moral Sentiments” book as primary to his philosophy, and “Wealth of Nations” should be read in its context (there is now a movie about this very issue, click here). In the above summary of Smith’s book, we can see that Smith understood the basic moral developments from the “reward seeking” orientation of the Subjective Sphere to the “approval seeking” orientation of the Cultural Realm, ending up with the “internalized spectator” of formal operations and the Sphere of Character.

For the most part, formal operations are associated with civilization and its accomplishments: literature, law, advanced mathematics, architecture, agriculture, politics, trade, science, etc. But the only necessary function of abstract reasoning is “soul-searching.” Civilization is not sustainable without ethical codes such as the Torah or the Code of Hammurabi.

Although literacy and urban life extend formal operations into many domains of life, they are not necessary to the development of abstract reasoning. Ramakrishna, the great spiritual master of India (1836 – 1886) was illiterate, but his soul-searching reached the heights of eastern spirituality; aside from his following in India, his message has been brought to the west by artistic luminaries such as Romain Rolland (French novelist and biographer who also wrote the first biography of Gandhi) and Phillip Glass (modern minimalist composer who published his opera, “The Passion of Ramakrishna”, in 2012).

Indeed, around the age of puberty, every culture has its rites of passage that transform the initiate from a participant in cultural performances to a contributor to cultural institutions.

One way or another, youth get knocked off their competency game, whether it be by puberty itself, or cultural rites of passage, or simply the cognitive demands of high school education. The concrete “ideas” of late childhood are developing into the abstract “theories” of youth. In this sense, formal operations and character development mirror the development of skepticism as researched by William Perry (1998).

But not all youth and young adults evaluate their theories in the same ways. Some take on their theories as beliefs, and use their abstract reasoning skills for “theory preservation” (Paul Klaczynski, Motivated Scientific Reasoning Biases, Epistemological Beliefs, and Theory Polarization: A Two-Process Approach to Adolescent Cognition,Child Development, Sept./Oct. 2000, 71, no. 5 pp. 1347-1366). For those who might think that these conclusions are themselves based on “motivated reasoning” to preserve more relativistic perspectives, the conclusions of the study are enlightening and solid:

Finally, epistemological dispositions were negatively associated with analytic reasoning biases and with theory polarization but were positively related to reasoning competence as indexed by total reasoning scores. “Knowledge-driven” adolescents — those who placed primacy on logical (versus intuitive) knowledge acquisition, and who appeared to subordinate the goal of theory preservation to the goal of learning — were more competent thinkers than belief-driven adolescents and showed greater balance in the use of their abilities. Yet, these adolescents had theories as wide-ranging as those of belief-driven adolescents. It is not, therefore, the relative neutrality of their theories that separated knowledge-driven from belief-driven adolescents; rather, the competence-performance gap was smaller for adolescents motivated to understand knowledge and its origins.

Knowledge-driven adolescents may have been more metacognitively careful than their counterparts and may have consistently monitored the quality of their justifications as they moved from problem to problem. Regardless of the relation between evidence and their theoretical beliefs, these adolescents engaged in predominately analytical processing and rarely lapsed into heuristic processing, as shown in Figure 2. Presented a challenging task, knowledge-driven adolescents, motivated by the desire to look beyond superficial task characteristics, were more likely to decontextualize beliefs from reasoning than adolescents whose predominant goal was theory preservation. (pp. 1360-1361)

The findings on “theory polarization” are crucial for understanding the development of abstract reasoning and its relation to life as a whole. Theory polarization not only involves over-looking the weaknesses of own’s own arguments and the strengths of competing arguments, but involves stereotyping of the competing theories and often imputing “underlying motives” to those who hold those theories. Global-warming deniers are a case in point: not only do most of them rely on theories that have been dis-credited, but claim that those concerned about global warming are not concerned about the planet and its habitability for animal life, but only want to control others and get research money for their “cronies.” “Motivated reasoning” in this case takes the forms of avoiding the scientific evidence and consensus, changing the subject, and smearing or even suing scientists with whom they disagree.

Back to the initial development of abstract reasoning in the young adolescent, I want to cover two issues: the “character” of Character Formation, and routes to get there in different domains.

Loevinger (1976) describes the shift from Conformist to Self-Aware stages as follows (pg. 19):

Two salient features from the Conformist Stage are an increase in self-awareness and the appreciation of multiple possibilities in situations. A factor in moving out of the Conformist Stage is awareness of oneself as not always living up to the idealized portrait set by social norms. The growing awareness of inner life is, however, still couched in banalities, often in terms of “vague” feelings. Typically the feelings have some relation of the individual to other persons or to the group, such as lonely, embarrassed, homesick, self-confident, and most often, self-conscious. Consciousness of self is a pre-requisite to the replacement of group standards by self-evaluated ones, characteristic of the next stage.

In relation to this, Loevinger, Kegan and Perry all point out that most youth start their analytic careers by questioning the standards in certain domains but not in others (what Loevinger call Conventional-Conscientious). Only later is their skepticism generalized to question the group standards they identify with.

This is true of young people who enter adolescence with supportive relationships with family and/or friends. Indeed, many youth who do not enjoy these supports, such as foster youth, have a hard time getting past the Self-Protective Stage because they have a risk-prone temperament (difficult or slow-to-warm-up) and don’t make friends easily, especially when moving frequently from placement to placement.

But we can see from some youth who are orphaned or children-of-divorce, that this is not always the case, and some resilient youth can develop quite readily in spite of the multiple stressors they face. These youth tend to become healthy sceptics (not cynics) about all areas of life: themselves, adults and peers. So, for instance, a child of divorce who lives with one parent who serves them up a daily portion of “bad-mouthing” the absent parent, when older will ofter gain enough experience of the other parent to turn their allegiance against the “custodial” parent, using their moral lapses to condemn them more roundly than the previously absent parent. Detecting hypocricy can be a strong suit for young people in this situation.

A more general and stunning illustration of this phenomenon is the fictional story of the orphan Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (1847 ). At age 10 Jane is living with her aunt whose son, John Reed, bullies her. When Jane finally tries to defend herself against her cousin, her aunt calls her a liar and locks her in the room in which her father died. When Jane is finally brought to account before her aunt, who gives her a morality book about lying, she tells her:

“I am not deceitful: if I were, I should say I loved you; but I declare I do not love you; I dislike you the worst of anyone in the world except John Reed: and this book about the Liar, you may give it to your girl, Georgiana, for it is she who tells lies, and not I.” (Bantam, 2003, pg. 33)

Strong stuff for a 10 year-old, but for those who are familiar with the English literature of Charlotte Bronte, Jane Austin, Virginia Woolf and Georgette Heyer, this is the kind of realism that can be expected from authors who are able to detail the thoughts, feelings, experiences and interactions of well-developed characters. [For more on Jane Eyre’s character development and spiritual formation, see the paper on Literary Depictions of Developmental States linked here.] Carol Gilligan knows this literature well, and references it when she explores women’t development (e.g. A Different Voice). In a recent PBS interview (Makers Profile: Carol Gilligan link), Gilligan gives a good example of this perspective when she asked a woman what she thought of something, and the woman replied: “Do you want to know what I think, or do you want to know what I really think?” This interviewee understands that it is best to confide in people one finds trustworthy.

Thus far, we have explored the ethical and interpersonal aspects of Character Formation; now it is time for something completely different!

There are sometimes interesting mathematical correlates to social and emotional developments, and my professional experience has reinforced this notion. So now I am going to detail the way I helped an 11 year-old special education student, who was gifted at math, shift from concrete arithmetic computations to abstract algebraic computations by means of teaching him a version of “Casting Out Nines”:

This 11 year-old middle school special education student was referred to me because there was friction between him and his math teacher. Although the student was very successful at getting the right answers on math questions, he could not show his work. This lowered his scores on many tests and threatened his math education. Both teacher and student were frustrated by this circumstance.

I decided to try a novel approach with him that I had been developing with other students, using math metaphors for dealing with interpersonal issues. In this case I focussed directly on the times tables of 9’s, first testing his memory of this part of the times table. So I write on the board the table as follows for him to fill in the answers:

9 X 1 =

9 X 2 =

9 X 3 = etc. etc.

He was able to supply the correct answers pretty readily. So the next step was to put “plus” (+) signs between the ten’s and one’s places of the answers, with an “equal” (=) sign afterwards, so that he could do another calculation:

9 X 1 = 09 / 0 + 9 = 9

9 X 2 = 18 / 1 + 8 = 9

9 X 3 = 27 / 2 + 7 = 9

9 X 4 = 36 / 3 + 6 = 9

9 X 5 = 45 / 4 + 5 = 9

9 X 6 = 54 / 5 + 4 = 9

9 X 7 = 63 / 6 + 3 = 9

9 X 8 = 72 / 7 + 2 = 9

9 X 9 = 81 / 8 + 1 = 9

9 X 10 = 90 / 9 + 0 = 9

9 X 11 = 99 / 9 + 9 = 18 / 1 + 8 = 9

9 X 12 = 108 / 1 + 0 + 8 = 9

9 X 13 = 117 / 1 + 1 + 7 = 9 etc. etc.

So my question to the student is, “Why all the 9’s?” At which point his eyes are spinning, and he can only wait on the edge of his seat for an answer. Then I point out to him that as you go down the ten’s column, it goes up, “0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 etc.” And then as you go down the one’s column, it goes down, “9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, etc. etc.” So this is the clue.

He is further on the edge of his seat, and it is now my professional duty to prevent him from falling off. So I conclude, “It is because 9 = (10 – 1). Each time you go up ten, you also go down one.”

He sits there contemplating this revelation, and then I show him an example:

9 X 6 = 6 (10 – 1) = 60 – 6 = 54.

With a few more examples, he gets the concept, and has now transferred his times tables for 9’s to an algebraic formula. (It was agreed that this student needed no further counseling after this intervention.)

Later in my career, one of my supervisees, after being trained in this intervention, pointed out how the operation can be done on one’s ten fingers (from 9 to 90 by progressively bending one uncounted finger down, tens to one side and ones to the other). I have since found that it is linked to the more general concept of “casting out nines.” (link)

CHARACTER COMPARISON

Tried to make it real compared to what? — “Compared to What” by Les McCann and Eddie Harris, Swiss Movement 1969.

Life-span developmental literature generally seems to consider the above description of Character Formation to be the normative stage where many if not most youth and adults settle in. Many people establish their ideas of life, fairness, and relationships on that basis, choosing certain beliefs, attitudes and opinions with like-minded individuals, while managing the complexities and ironies of life as best they can, adding to the chosen social conventions a dollop of common sense and personal philosophy. Mostly they follow the conventional expectations of society, performing as best to standard as they can, but ultimately disappointed in their short-comings. Research suggests that their entrenched approach to life will serve them poorly in old age, resulting in low sense of self-worth and life-satisfaction as the losses of spouse, friends, work and health take their toll in an embittered attitude (F. Clark Power, Ann Power and John Snarey, Integrity and Aging: Ethical, Religious, and Psychosocial Perspectives, in Lapsey and Power, Self, Ego, and Identity, Springer-Verlag, 1988).

But for those of us who trudge on, for the sake of learning, discovery, and enhanced life possibilities, our skepticism generalizes and becomes able to better compare the strengths and weaknesses of different theories. One important generalization is that theories have authors whose lives and works can be evaluated. This was the great realization of the first “modern” historian, the Venerable Bede (673-735) who understood that history had generally been written by the victors of war and was slanted accordingly to make the victors appear deserving of their spoils. Bede was very careful to use multiple sources, relying not just on an extensive library, but he also had access to original documents and accounts from colleagues. In other words, a reliable historian should “consider one’s sources” and not just take legends at face value.

In the technical domains, youth in the mid-to-upper teens are able to do more advanced mathematics such as algebra and geometry. Understanding graphs with X and Y coordinates (such as bar graphs), including the full-fledged Cartesian Coordinates (1637), comes within these developments. Keplerian astronomy (1609) fits in this mold, where elliptical orbits are mapped on graph paper according to a mathematical formula. Although elliptical models of orbits are more accurate than circular ones, ellipses still require “retrograde” adjustments to be even more accurate. This is because Kepler’s model assumes that all the gravity in the system resides in the object at the “center” of the ellipse (e.g. the sun relative to the orbiting earth). A more realistic, Newtonian model (1687) takes into account the relative mass of the Earth which exercises a gravitational pull back on the Sun as it is pulled more strongly in its orbit around the Sun.

CHARACTER RELATION

Included in the developments of this stage are all the advanced and coordinated deductive systems such as most science and mathematics (including Newtonian calculus), as well as ethical and legal systems (e.g. Kantian ethics).

I inherited a mind for math from my father who was the aerospace engineer and lead scientist developing the hydraulic systems for retractable landing gear in jets during WWII. My interests in history and psychology led me away from pursuing a career in math and science — consequently, the most advanced math I mastered was trigonometry (which makes the focus on the double-helix possibly a remnant of my adolescent mathematical mind) and the most advanced science was three quarters of astronomy at UC Santa Cruz (which has internationally-renowned research facilities and graduate studies in astronomy).

Scientific philosophers have postulated that deductive procedures are infallible as long as all relevant inputs are included in the deductive process. I am willing to accept this proposition at face value: what I will not take at face value is that any single deductive act has indeed included all relevant inputs. A good name for this phenomenon might be the “Deductive Uncertainty Principle” which probably has similarities to Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle of Physics. For me, the “take away” truth from this is that deduction is best used as a tool for decision-making, and should not be held as the rule for all decision-making. As Paul Ricoeur notes (The Rule of Metaphor, Univ. of Toronto, 1975, pg. 242), deduction does not lead to discovery — it only narrows the choices already being considered. In this sense, deduction should serve discovery and not constrain it.

On the more personal domains, young adults face the life-choice decisions that emerge with the crowning question of skepticism: Who am I? (see Perry 1981, pg. 79) Their experience cannot but compel them to eventually conclude that their identity is partly determined by choice and partly by temperament and experience. But even the freedom to choose involves another side — whenever we choose to take on one thing, we also de-facto choose to let go of the other choice, constraining our experience by our choice. This makes Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer (1951) relevant: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Although the Serenity Prayer was adopted by Alcoholic’s Anonymous, there is a non-AA version of this circulating: “Lord, give me coffee to change the things I can, and wine to accept the things I cannot.”

Unfortunately, coffee and wine cannot give us the wisdom to know when to drink coffee and when to drink wine. Wisdom will have to wait until we get beyond the deductive dilemmas of character development.

A challenge that I faced in the later years of high school and in college was male peer pressure (not friends or females) that in one form or another tried to label me as “naive” if I was not vocally cynical (I did not find this peer pressure in graduate school, but I was in a social work school then and not in business school where selfish motives are assumed to be the norm). This “either/or” attitude of “you are cynical or naive” can be translated into “both/and” endeavors of how to be sceptical without being cynical and how to be hopeful without being naive.

Before I graduated from high school, I wrote a paper for a psychology class which summarized Jean Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness in 8 pages (the teacher who assigned me that project also guided me in the direction of Jacques Maritain’s existentialism, as did other college professors). Out of that high school experience, I sought to discover and generate an “assumptionless” philosophy using phenomenology (e.g. Edmund Husserl and Alfred Schutz) to identify and “strip away” assumptions. What I finally found was that the assumption that one can live life based on an “assumptionless” philosophy to be a pretty poor assumption. My endeavor then shifted from identifying assumptions for the purpose of getting rid of them to identifying assumptions for the purpose of choosing the better assumptions to employ in order to enhance life.

There are many ways to look at the dynamics of Character Relation, which include the struggles to balance self and others, discipline and indulgence, realism and altruism, justice and caring. If we only care for ourselves, we do an injustice to others; if we only care for others, we do an injustice to ourselves. The pushes and pulls entangle this system in a web of unresolved relations, potentially compiling complexities that serve to dampen decisive actions and commitments. One version of this is the Kantian “categorical imperative” that dictates that principle should be the only guide to action, damn the consequences. The admirable fact that most women won’t go along with this stricture seems to be the main reason Kant considered women incapable of complex abstract reasoning. Tell that to Hannah Arendt, Barbara Tuchman, or Margaret Visser (or Miss Manners, for that matter!). Ultimately it is the balance and complementary relationship between truth and love that counts toward developing a spiritual perspective. In this sense, there is a formula that:

Truth without Love = rigid discipline = overly punitive

Love without Truth = unruly indulgence = overly permissive

When Perry writes about the shift from relativism to commitment, the commitments he is talking about are to people (e.g. marriage) or causes (e.g. professional missions and ethical guidelines, generally to do no harm, or social justice efforts), not abstract principles. If a principle does involve the importance of consequences for people, it is more than a principle: it is a value.

Principles are followed, values are balanced. Except when defending ourselves against attack, it is our adult responsibility to provide the proper levels of support and challenge to the people we deal with in difficult situations. As we do so, we need to assess the relevant levels of responsibility of the involved parties: immediately traumatized people need immediate support, infants need support and guidance, children and youth need to learn responsibilities, and adults need to be responsible while finding the necessary supports to maintain those responsibilities. There are various balances that need to be struck in order to help with difficult situations. These are some of the broad guidelines I used in supervising clinical social workers to provide beneficial services to families and schools, where various complementary and conflicting agendas prevail. To deal with multiple levels of complexity, one need to have a hearty tolerance of ambiguity in order to untangle the dysfunctions.

I think this is the most appropriate point to mention Jane Loevinger’s most significant contribution to social science: her finding that the Authoritarian Personality (identified because of the Nazi threat to world peace presented by Hitler) was based in an intolerance of ambiguity rather than some psycho-sexual anomaly. Ideology does not accept ambiguity for any period of time — the task of ideology is to eliminate ambiguity (you are either with us or against us) at the first opportunity. We cannot reasonably tolerate ambiguity without developing critical thinking, considering sources and motives and self-deceptions. One of the primary training, supervision and co-treatment goals I evaluated with the clinicians I supervised was how well they tolerated ambiguity while maintaining friendly helpful relationships with all involved parties to any social problem.

An interesting description of what it is like to be trapped in the “either/or” world is given by Gil Noam (1988) who uses Franz Kafka’s Letter to my Father (1953) to show how complex abstract arguments can hamstring one’s sense of efficacy in life, resulting in the kind of despair reflected in Kafka’s novels The Trial and The Castle (neither of these novels have endings, and neither the first-person narrator nor the reader know what is really going on in either of the legal or bureaucratic nightmares) and his most famous story, The Metamorphosis (in which the first-person narrator is turned into a cockroach without any rhyme or reason). Kafka’s worlds are worlds without choices or intimate relationships, prompting Noam to call Kafka “A Prisoner of Adulthood” (from “The Self, Adult Development,and the Theory of Biography and Transformation” in Lapsey and Power, eds. Self, Ego, and Identity, Springer-Verlag, 1988, pg. 18).

So commitment does involve positively choosing one’s assumptions, which means at least a temporary “suspension of disbelief”. In his song Word on a Wing, David Bowie writes (1976):

Just because I believe don’t mean I don’t think as well,

Don’t have to question everything in heaven or hell.

This is a strong statement from the androgynous rocker who made his career on questioning everything in heaven or hell with hit songs and characters such as Major Tom, Bewley Brother, Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke (not to mention the Elephant Man and the Man Who Fell to Earth). But by the time Bowie wrote Word on a Wing, he realized he had to leave the frenetic cocaine scene in Hollywood and slow down in Berlin under the calming guidance of Brian Eno. Otherwise his relationships and career would have crashed and burned. (If you have questions about the meaning of these lyrics, listen to Bowie’s introduction to the song on VHS Storytellers, 2009 MTV; full transcript link here.)

Along these lines, Jon Anderson, founder and lead singer of Yes, sings in the vein of Pascal’s wager: “Better to be sacred than sorry.” (from the song “Youth”, on his solo record The More You Know, Eagle Records, 1998).

And now on to spiritual discovery!