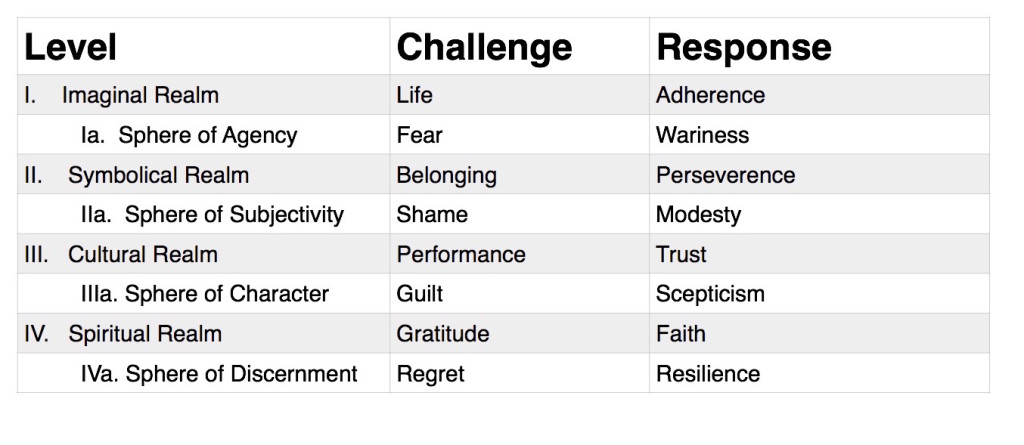

(bottom)Developmental Challenges and Adaptive Responses

Outlined below are the developmental challenges presented at each level of development and the adaptive responses that lead to continued social and emotional growth. It has similarities to Erik Erikson’s model, but differs in various ways (such as having two stages in infancy — image and agent — whereas Erikson one — basic trust vs. mistrust).

Imaginal Realm: Initially the challenge for the infant is life itself — for the infant to thrive it must adhere to life. If the infant’s body or environment are too unhealthy, it can fail to thrive (even with a lack of caregiver bonding, first described by James Bowlby as “hospitalism”).

Next the infant uses the caregiver attachment as a base to explore the unfamiliar and possibly unsafe world. In order to do this the infant needs to be able to “go to” the unfamiliar and “get back” to the caregiver as an agent. The infant now can begin to regulate the fight or flight instinct and face fear with wariness as a way to learn about the unfamiliar.

Symbolical Realm: Language brings the child into the social world of family and visitors where the child has a “place” to belong. It is important for the child to persevere in learning language and other skills to thrive in the newly symbolic world. Parents should “bathe” their child in language to boost her learning and ability to belong.

Next the child learns that his impulsiveness and the expectations of self-regulation (clothing, toilet-training) create challenges to belonging that generate shame. Through the internalization of language, the child learns how to “stop and think” in order not to be rude or an embarrassment. These self-control skills are crucial to life-long social success.

Cultural Realm: School age children who have sufficient self-control skills can shift their attention to fulfilling the roles they take or are given. These roles require that the child promise to learn how to be competent at the tasks involved and promise to perform those tasks when required by the role (e.g. a student does his homework). Children are “enculturated” into these roles and learn them by trusting a mentor. These performances are “concrete operations,” and have no way of evaluating the performance outside the standards of the performance itself. Other ways of doing things are generally considered the “wrong way.”

Next the adolescent discovers that a perfectly competent performance can be wrong because it is evaluated in a different context. For instance, someone who is good at tricks on the bicycle and who might be applauded for winning a competition is likely to get a different response doing the same tricks on a crowded side-walk. He may be sure of his skills to avoid hitting anyone, but others are likely to be startled and could have an accident because of the unexpected distraction. Without a sense of guilt and skepticism of one’s own motives and developing character, “performance artists” tend to become narcissistic. The abstract skills of “formal operations” allows youth to evaluate their assumptions and beliefs as theories and conceptions rather than as final and absolute truths. In a similar way, trust in individual mentors can be challenged or broken by disappointments or betrayals.

Spiritual Realm: Adults who have established a stable identity and a trustworthy character are often burdened by the demands of their own conscience and inflexible problem-solving styles. This is where the “intuition of being” and gratitude become life-savers because when you don’t take anything for granted, everything becomes a gift to be grateful for. This allows one to have faith in humanity even when trust in an individual has been lost. It also allows one to entertain, or be entertained by, multiple perspectives which can then help with more imaginative and flexible problem-solving styles, and more harmonious relations. One learns how to be more giving without being taken advantage of.

In the end, we ultimately come up against the final limit, death, no matter how spiritual we have become. At the same time many experience the living death of oppression, imprisonment and torture. In these circumstances, a strong-hearted spirituality helps provide the discernment to maintain a sense of humor, perceive who is a friend and who is an enemy, and project forgiveness as a difficult reality and not wishful thinking. Regrets are faced with the perspective that “the only sadness is the sadness of not being a saint” (Peguy), establishing a spiritual resilience that isn’t hampered by unnecessary fear, shame and guilt. We can see this resilience in the examples of Nelson Mandela (victim of apartheid) and Dietrich Bonhoeffer (victim of the Nazis).