I first learned about Thich Nhat Hanh in a class taught by Donald Nicholl at UC Santa Cruz (“Holiness in World Religions”) in 1978. Nicholl may have been the first western writer to mention Nhat Hanh’s mindfulness practices in his book Holiness. I expect that Nicholl met him through their common friendship with Thomas Merton (Seven Story Mountain). (Nicholl and his wife were also good friends with Erik and Joan Erikson.)

Thich Nhat Hanh was born in Vietnam in 1926 and became a Buddhist monk at the age of 16. Here is a description of the community in which he became an adult and its abbot:

The fundamental training of a novice in Vietnam is essentially to practice being present in every moment and to do whatever one is doing with full awareness. Nhat Hanh lived among the forests and gardens of Tu Hieu with his community of brother monks, studying and practicing under the guidance of the abbot, a wise and experienced teacher who loved and understood its students. (At Home in the World: Stories and Essential Teachings from a Monk’s Life, Parallax Press, 2016, pg. 183)

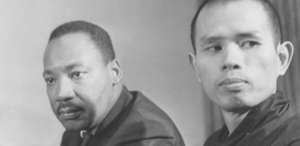

Nhat Hanh became a teacher himself, and studied comparative religions in the US. During that time he met Thomas Merton and Martin Luther King, Jr. with the result that he convinced MLK to oppose the Vietnam War. MLK returned the favor by nominating Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967 (nobody got the prize that year because it was considered unusual for a member of the committee to nominate someone themself). As a result of his anti-war stance, Nhat Hanh lost his visa in the US as well as his Vietnamese citizenship, rendering him a nationless exile for 40 years. France have him asylum, and he was able to establish his spiritual community there, which has spread to “nine practice centers and monasteries worldwide, in at the US, Europe, Asia and Australia, where his monastic students, today numbering over six hundred, share mindfulness practices in what is now known as the Plum Village Tradition. There are also over one thousand lay Sangrias, communities of people practicing together, world-wide.” (At Home in the World, pg. 186) His communities have taken on various good works, including saving Vietnamese “boat people” who would have been left to die by the international community without the direct intervention of Nhat Hanh and his disciples, many of whom lost their lives in the effort.

Late in 2014, Nhat Hanh suffered a serious stroke:

On his eightieth birthday, when asked if he planned to retire, Nhat Hanh said, “Teaching is not done by talking alone. It is done by how you live your life. My life is my teaching. My life is my message. (pg. 187)

A good idea for us all, including Ken Wilber.