Benefits of the Double-Helix Model

“The map is not the territory.” — Motto of cybernetics, Korzybski, A. (1948).

In the same way, the model is not the reality. None-the-less, here are the primary ways in which the double-helix model is more fitting to describe and predict bio-pscho-social-spiritual development than the current dominant spiral models:

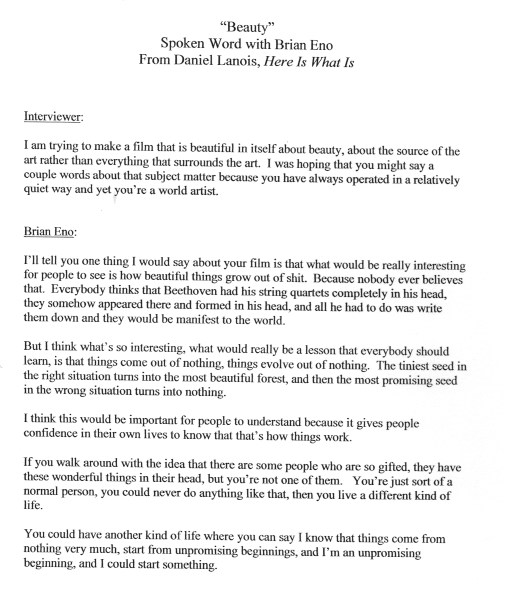

The Double-Helix and Development

In contrast to a spiral model of development, the double-helix has two strands allowing it to carry more information. In particular, it identifies the key turning-points of development and their nature in relation to each other.

Savoring and Coping Skills (green for go, red for stop)

The double-helix model depicts the relationships between savoring skills and coping skills. With savoring skills we find and explore opportunities; with coping skills we define and apply limitations. This occurs at each of the major stages of development: imaginal, symbolical, cultural and spiritual.

Intuition and Mutual Attention

By tracking the sub-conscious strand of the development of consciousness, the double-helix model appreciates the role of intuition throughout development. In particular, it helps us to understand how intuition is enriched and refined for learner and teacher with their mutual attention in the “zone of proximal development.” (Vygotsky)

Gratitude and Post-Formal Operations

The double-helix model clearly illustrates the position of gratitude in relation to the closed systems of formal operations. It reinforces the need for analogical thinking in flexible adult problem-solving, maturity and happiness. (Steindl-Rast)

INTRODUCTION

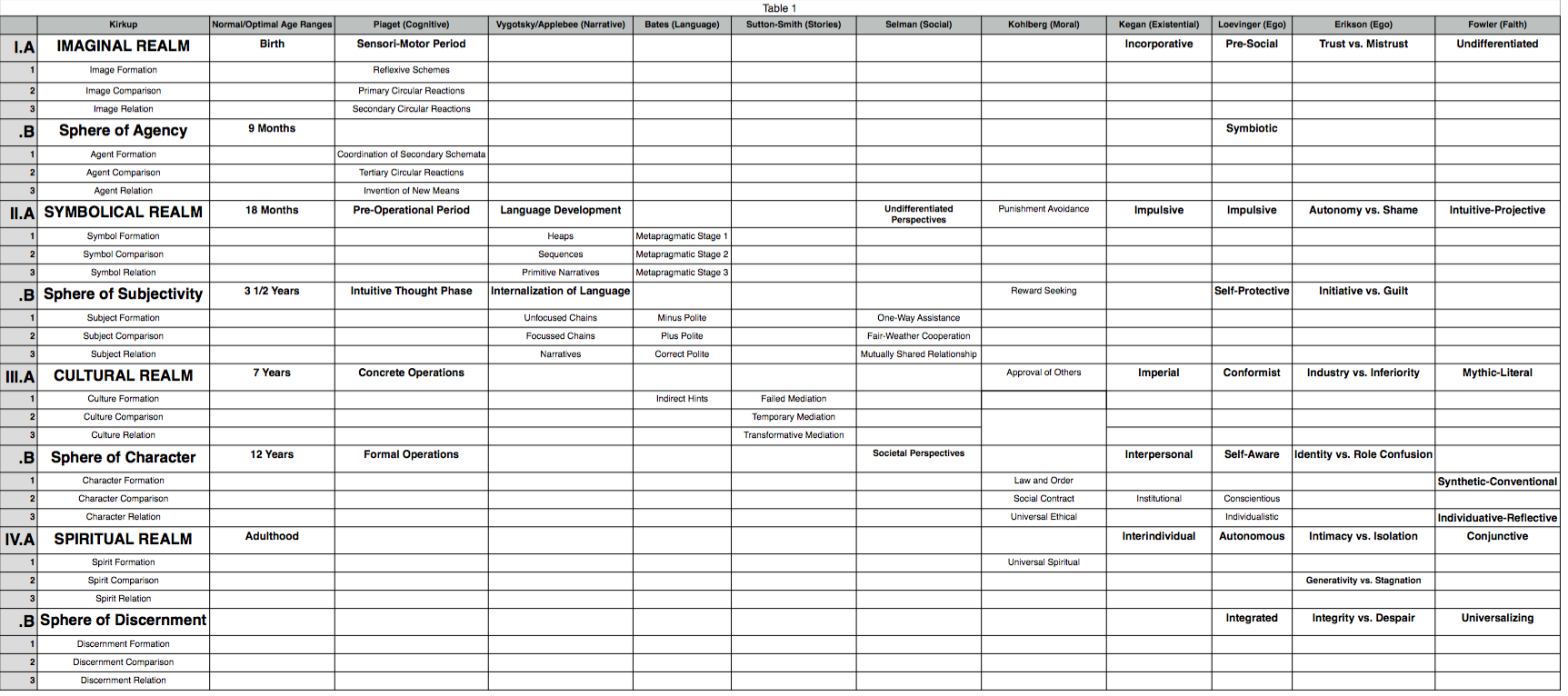

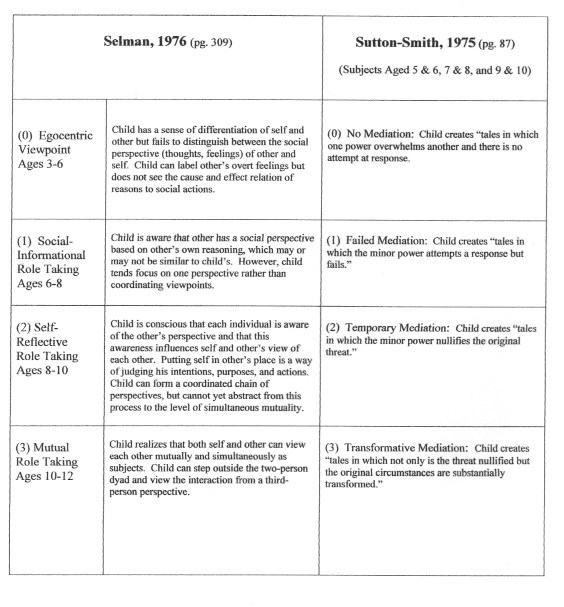

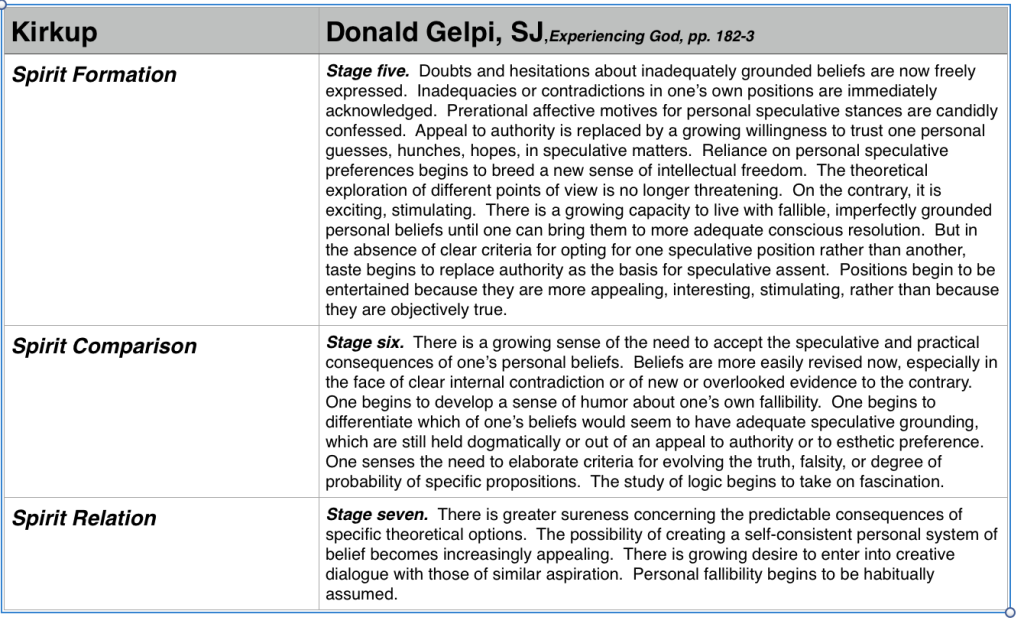

This section includes cross references between the double helix model and the findings of developmental psychology and spiritual development, including Erik Erikson, Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, Jerome Bruner, Elizabeth Bates, Robert Selman, Brian Sutton-Smith, Lawrence Kohlberg, Carol Gilligan, Robert Kegan, Jane Loevinger, William Perry, Michael Basseches, Klaus Riegel, James Fowler and Robert Cole. I will also include a series of participant-observer studies I did with children to highlight certain key developments.

I was privileged to be in the middle of a research explosion in developmental psychology from 1975 to 1985 while an undergraduate and in graduate school. More recent findings have generally reinforced the discoveries of that 10 year span. The training and supervision I have done over the decades with social work students and interns has supported this view, as well as the general resource books I have used to get up to date in the field:

The Developing Person Through the Life Span (8th ed.) by Kathleen Stassen Berger (2011: City College of New York).

Identity in Adolescence: The balance between self and other (3rd ed.) by Jane Kroger (2009: Rutledge).

Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy by Ken Wilber (2000: Shambhala).

This grid can be zoomed in on by clicking on the image and then using the magnifying glass icon (for easier to read sections of this grid, go here):

PRIMARY SOURCES

These are arranged generally in the developmental order, from infancy to adulthood, that I use the research finding — e.g. Piaget for sensor-motor development during infancy, Fowler for spiritual development during adulthood. .

Piaget, Jean: The Origins of Intelligence in Children (International Universities Press, 1952)

Piaget, Jean: The Insights and Illusions of Philosophy (Meridian Books, 1971)

Korzybski, A. (1948). Science and sanity: an introduction to non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics (3rd. ed.) Lakeville, CT: Int. Non-Aristotelian Library Publishing Co.

Vygotsky, Lev: Thought and Language (MIT, 1986)

Applebee, Arthur: The Child’s Concept of Story (University of Chicago, 1978)

Bruner, Jerome: Child’s Talk: Learning to Use Language (Norton, 1983)

Bruner, Jerome: Actual Minds, Possible Worlds (Harvard, 1986)

Bates, Elizabeth: Language and Context (Academic Press, 1976)

Sutton-Smith, Brian: The Importance of the Story-Taker, in Urban Review (1975), 8, 82-95; The Folkgames of Children, American Folklore Society, 1972.

Selman, Robert: Social Cognitive Understanding: A Guide to Educational and Clinical Practice, in Moral Development and Behavior: Theories, Research and Social Issues (Lickona, ed.; Hold, 1976, pp. 299-316); The Child as a Friendship Philosopher, in The Development of Children’s Friendships (Asher and Gottman, eds.; Cambridge, 1981), pages 242-272.

Kohlberg, Lawrence: Essays on Moral Development, volumes 1 (1981) and 2 (1984) Harper and Row; Private Speech: Four Studies and a Review of Theories, Child Development, Sept. 1968, vol. 39, vol. 3, 691-736; Early Education: A Cognitive-Developmental View, Child Development, Dec. 1968, vol. 4, 1013-1062; The Cognitive-Developmental Approach to Moral Education, Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 56, no. 10, June 1975 pp. 670-677.

Kegan, Robert: The Evolving Self (Harvard, 1982); The Loss of Pete’s Dragon: Developments of the Self in the Years Five to Seven, in The Development of the Self, Leahy (ed.), Academic Press, 1985, pp. 179-203.

Loevinger, Jane: Ego Development (Jossey-Bass, 1976); On Ego Development and the Structure of Personality, in Developmental Review 3, 339-50 (1983); Confessions of an Iconoclast: At Home on the Fringe, Journal of Personality Assessment, 2002, 78 (2), 195-208.

Perry, William: Forms of Ethical and Intellectual Development in the College Years: A Scheme, Jossey-Bass, 1999; Cognitive and Ethical Growth: The Making of Meaning in The Modern American College, A. Chickering (ed), Jossey-Bass, 1981.

Erikson, Erik: various sources

Fowler, James: Stages of Faith (HarperOne, 1981), and others.

The reason that Jerome Bruner is not represented on the grid is that he did not label the developments he described — he simply described them in narrative fashion. But Vygotsky and Applebee’s “vygotskyian” research on children’s concepts of stories can be identified with Bruner’s thinking. A lot of the style and content of this section are influenced by Bruner who identifies more common experiences with more common language to “tell the story” of development (rather than jargon-laden explanations of laboratory results). Bruner pioneered the “videotape in-home naturalistic interactions” method, a variation on Robert Coles’ “participant-observer” methodology, which explicitly takes into account the effect that observations have on phenomena.

META-ANALYSIS

Before detailing the research findings that I have lined up with my 4 levels, 8 stages and 24 steps, let me make some general comments on the patterns and findings. Of course, this is my take on the research, and I expect there to be some controversy about my claims. But after scouring the research for decades, as well as my 35 years practice in community mental health with children, families and schools, I have discovered some things that are not yet in the literature.

At first glance it is apparent that the double-helix model aligns most directly with Jane Loevinger’s model. No other model aligns with all 8 stages of the double-helix. My theory is that this is for two reasons: 1) Loevinger’s model is the most empirically based of all the models on life-span development (see Kroger, 2009); 2) Loevinger understands the abductive method better than other theorists, making her model more open to detecting important aspects missed by other models (see Loevinger 1983, pg. 344).

Language Development

One of the deficiencies in the developmental literature I have noticed for 35 years is the general neglect of Vygotsky’s findings on language development and the internalization of language. Jerome Bruner tried to rectify this in the 1970’s and Kathleen Stassen Berger has admirably given Vygotsky his due in her textbooks, but there is no reference to Vygotsky in Kohlberg after 1968, and none that I have found in Loevinger, Kegan, Fowler, Wilber, or even Elizabeth Bates. As a result, both Kegan and Fowler totally miss the important developments associated with the internalization of language. Bates captures similar developments with her polite forms, and Loevinger captures these developments with her “Self-Protective” stage. This deficiency is particularly significant because the self-control skills developed with the internalization of language are a major contributor to life-long well-being and happiness. In evidence-based interventions such as Aggression Replacement Training (ART), Vygotsky’s theories are central to the use of self-talk and role-playing exercises for effective outcomes (more on this later).

So this is not just an academic matter. There is a bias about this period of development that comes from Piaget who, in studying the “Pre-Operational” child, focussed more on what the child didn’t understand (e.g. “conservation”) than what the child was learning (self guided behavior). This led to a view of the “Pre-Operational” child as “ego-centric.” This bias even led Ken Wilber to downplay ideas of children’s spirituality because their thinking is too “egocentric” (pg. 140). I understand and concur with Wilber’s caution against romanticizing or sentimentalizing children’s spirituality, but using a stereotypical sledge-hammer is not the way to go about it.

Indeed, it seems to me that this debate goes to the heart of the whole “constructivist” enterprise based on Kantian principles of deduction. Based on the principle of “ought implies can” (e.g. you should not expect something of someone unless they are capable of doing it), the constructivists assume that in order for a skill to be “expressed,” it must first be acquired as a cognitive capacity. The specific skill is deduced from the general capacity.

The result of this is that the cognitive domain is treated as the primary “underlying” structure that then gets expressed in other domains such as social, moral, emotional, instrumental, theoretical, etc. And how is this “underlying structure” acquired? We are told this happens through “assimilation” and “accommodation.” Now I understand that this means that we approach reality with assumptions that need to be altered based on the feedback from reality. But if cognition is a content-free general capacity, what is the reality to which it accommodates? Some vague, abstract idea of reality? In contrast to this vague and abstract theory, Vygotsky’s description of the “zone of proximal development” describes the experience of acquiring new skills. This experience occurs in response to the particular realities of a domain.

The ramifications of these different views become apparent in the study of the acquisition of language. For Piaget, the symbolic capacity develops at the end of the sensori-motor period, after which the child “expresses” this capacity by attaching words to the symbols (in a sense, “dressing” the symbol for public expression). For Vygotsky, children acquire the symbolic capacity by learning the symbolic value of language (this is also true for sign language). Language and thought are fused until they diverge with the internalization of language. It is by interacting with the linguistic environment that children acquire the symbolic capacity, not the other way around.

In his Dec. 1968 article, Kohlberg tried to argue that symbolization and language are parallel developments and are never “fused” like Vygotsky claimed (pg. 1043). Aside from stating the claim, the only “hard” evidence he gives for this position is that language cannot be important for children to learn “conservation” (the “hallmark” of “concrete operations”) because deaf children are not significantly delayed in learning “conservation.” As an aside, this argument shouldn’t have had credibility in 1968 — but Kohlberg makes the argument twice in this paper (pp. 1033 and 1042), and today the argument is nothing short of silly (sign language is now known to reside in the same parts of the brain as verbal language — link). I find no evidence that Kohlberg ever revisited the issue, so with this one flimsy (more like broken) argument, Kohlberg dismissed a whole branch of developmental research.

It is interesting to note that in Kohlberg’s Dec. 1968 article, he cites approvingly of Sheldon White’s 1965 article Evidence of the Hierarchical Arrangement of Learning Concepts (in Advances in Child Development and Behavior, vol. 2, ed. Lipsitt & Spiker, Academic Press), showing how “concrete operations” involves a “watershed” of basic cognitive shifts (pg.1039). In White’s macro-analysis of 21 cognitive shift functions in the age range of 5 to 7 years old, he filters the results through various major developmental theories, and concludes: “Where Piaget has taken pains to describe the intellectual resources of the child at the terminus of the 5-7 period, the Russian material concentrates on processes leading into it” (pg. 211; coincidentally, White wrote this article with input from Bruner). Perhaps no starker expression of the Piagetian “deficit” view of the “pre-operational” child can be found than in Kohlberg’s quote in this context: “The approach sees the preschool period as one in which the child has a qualitatively different mode of thought and orientation to the world than the older child, one in which he is prelogical, preintellectual or not oriented to external truth values.” (pg. 1039)

To make things perfectly clear, the preschool child is not primarily learning about the world and external truth values, but rather about the self and means for controlling the self. This is how we understand the difference: for Piagetians, the child 3 to 7 has no cognitions worthy of note because they are “ego-centric”; for the Vygotskyians, the child 3 to 7 is learning how to control himself through self-guided and internalized speech. Thank goodness that Vygotsky was right, because we can expect self-control to develop in our children while we attempt to mold it with his idea of “scaffolding” and Bruner’s of “formats.”

The implications for parenting and education are enormous. If you value language and social interaction you will find ways to optimize these experiences. If not, the quality of these experiences will generally be neglected. Kohlberg shows this neglect when he addressed education approaches in 1975. He identified only three education theories, directive (indoctrination), non-directive (values clarification), and inter-active (Piagetian). In response to this Phi Delta Kappan article by Kohlberg, fellow Phi Delta Kappans (including Richard Peters, pg. 678) pointed out that there are at least eight identified moral reasoning approaches to education (pg. 677), that Kohlberg’s approach largely neglects the affective side of moral education, that these criticisms had been addressed to Kohlberg since 1969 and Kohlberg had failed to respond to these criticisms. Peters ends his Reply to Kohlberg by asking the question: “Why doesn’t Lawrence Kohlberg do his homework?” (Answer: because Kohlberg was too busy building his empire, so he found ways to try to dismiss Vygotsky, then Loevinger, without looking back — see page on the Loevinger/Kohlberg debate here).

Spiritual Development

Another area where the constructivist enterprise hits a snag is in the question of “post-formal” operations. To put it bluntly, you cannot understand “post-formal” procedures if you restrict yourself to the formal operational procedures of Kantian deduction. Kohlberg ran up against this when he went beyond moral universality to address the question “why be moral?” In order to address this question convincingly (with the help of F. Clark Power) he had to go beyond ideas of assimilation-accommodation and deductive procedures, using the abductive gestalt analysis of figure/ground shift to give a description of spiritual development (1981, pg. 345). Perhaps as an attempt to repent his straying from the rigorous constructivist line, he ended up calling “Stage 7” “soft” and “hypothetical” (1984, pg. 249) and continued trying to use formal procedures to convince Jurgen Habermas that Habermas’ “dialogical communication” could be incorporated into Kantian formalism (1984, pp. 384-5) using a “musical chairs” analogy. Before his suicide in 1987, Kohlberg dismissed the idea of a stage 7 (click link to the page on the history of the Kohlberg/Power/Fowler collaboration).

Something that the attentive reader might notice is that I have put a short leash on what I consider formal operations (what I call the sphere of character). It does not include the developments related to intimacy in other models, including Erikson’s “Intimacy vs. Isolation,” Kegan’s “Interindividual” Stage, Loevinger’s “Autonomous” Phase, and Fowler’s “Conjunctive Faith.” While formal operations establishes procedures for ruling out hypothesis and evaluating ethical options, it is by nature limited to its “either/or” conclusions. Intimacy requires more “both/and” options to thrive. [For good examples of spontaneous intimate commitment decisions, see this link to Jeff Bridges’ marriage decision, or this link to Bono of U2 telling his daughter how she saved his life when she saved hers as a newborn.]

Formal operations/character development involves evaluations of self, whether in relation to criteria of justice (Kohlberg) or caring (Gilligan). Either way it requires soul-searching. But intimacy cannot thrive on soul-searching alone. One must get outside oneself in order to become available to the other. Adding “moral musical chairs” (tacked on to soul-searching) isn’t enough. Inadequate metaphor.

Intimacy is not just a test of character, but also a spiritual practice involving intuition, empathy, imagination, communication, creativity and commitment. For intimacy to thrive requires wisdom, and wisdom is more than knowledge and discipline — it requires a spontaneous openness to reality and “the other.”

Lastly, in his later years Kohlberg tried to sideline Loevinger by saying that her stage descriptions were unsufficiently philosophical. I have read through the back and forth in the literature on this controversy. At the same time I wonder why Kohlberg almost completely ignored Bruner and Vygotsky. I don’t think there is anything in the literature and it might take interviewing the remaining associates of Kohlberg and Bruner to divine the reason. But my best guess is this: both Bruner and Loevinger, when they make overtly philosophical statements, reference Wittgenstein. A problem for Kohlberg with Wittgenstein is that Wittgenstein philosophized but did not have a philosophy. Kantian deduction forms a closed system which is an insulated philosophy that allows the rationalist to take the reasoning process out of the specific situation and “de-contextualize” or even “de-ontologize” the reasoning process (regardless of the real world consequences). For Wittgenstein, language does not exist outside of context — language does not stand on its own but is embedded in a situation. Context is open to language’s contribution, and language always in some ways references a context. It is an open system. Wittgenstein’s philosophizing allowed him to show that once you assume language exists outside of context, certain philosophical errors result. Kohlberg seems to have made some of these errors and was called out on them by Loevinger in her responses to his dismissive writings about her.

More on the relationships between induction, deduction and abduction (analogical thinking) will come later in this section, and more general consideration are to be covered in the philosophical perspectives section of this website. But before moving into the specific developments, let us look at this model in relation to Piaget’s theory and continuing influence.

The Double-Helix Model and Piaget’s Genetic Epistemology

Many researchers have followed Jean Piaget’s theory of genetic epistemology and its associated concepts of assimilation and accommodation, and the constructivist perspective on the development of logical reasoning, without sufficient critical review. The double-helix model opens it up to critical review, extrapolation, and development.

Piaget identified assimilation with Freud’s pleasure principle and accommodation with Freud’s reality principle (see Vygotsky, 1986, pg. 262). Although this is similar to affirmation (savoring) and negation (coping), there are significant differences. Piaget thinks of accommodation as slowly replacing assimilation as the egocentric child becomes more objective (a gradualist model) — at the same time that the developing person is “de-centering” their perspective they are also “dis-embodying” their thought (making it more abstract — what Kohlberg called “de-ontologizing,” or removing the content, from the process analysis).

In contrast, the double-helix pattern has four phases of accommodation where what is being assimilated is the coping skills themselves (the person is self-consciously focussing on how she is going to cope rather than on the savoring goal that the coping is meant to successfully achieve). First, the infant, attracted to sensory images, learns she needs to move herself as an agent to obtain what she wants. Next, the young child, now using language, learns that he is a subject of experience different from others’ experiences, and needs to be thoughtful of what he says and where he does private things. Further on, the adolescent, having learned to master some of the important performances that comprise their culture, learns that she will be judged by the content of her character — how she balances self-discipline and self-indulgence (and all the other polarities that confuse the adolescent). Finally, the adult that has gained a spiritual perspective of gratitude will at some point find himself needing to apply the spiritual discernment that is necessary to have good judgment without being judgmental and maintain a life-affirming attitude in the face of adversity. In Piaget’s model, abstract formal operations are the end point — in the double-helix model, formal operations are one domain of character development which is later subsumed under spirituality (if that is achieved).

In the larger picture, Piaget’s epistemology is stuck in the Kantian assumption that all knowledge is gained by the mind’s “invention” (Piaget’s phrase “to know is to invent”). In his Insights and Illusions of Philosophy (Meridian Books, 1971), Piaget puts forward the materialist scientistic view that there is no true wisdom beyond objective scientifically and quantitatively measured knowledge and that objective knowledge will eventually supplant notions of wisdom, making wisdom obsolete (in this, he included both psychoanalytic “instinct” theories and idealistic “wisdom” theories as naive and outside scientific consideration).

An alternative view is that knowledge is not only invented — it is also discovered. In this sense, we not only impose our mind’s templates on reality, but reality itself is open to discovery in its various aspects. And it is the reason I think that all constructivist models of development (including Kohlberg and, I would argue, Robert Kegan) are on shaky foundations, because any model that excludes the “logic of discovery” (Karl Popper) is not in my mind “true to life.” This perspective appears to me to be consistent with Vygotsky’s critique of Piaget (Thought and Language, MIT, 1986) and Jerome Bruner’s overview of The Culture of Developmental Psychology (Actual Minds, Possible Worlds, Harvard, 1986). In Bruner’s article, he lays out the range of views on developmental psychology, from the emphasis on instinct by Freud, to the emphasis on cognition by Piaget, and finally to the more balanced view of Vygotsky that brings body and mind together in intuition and the “zone of proximal development” (the social process of mentoring by parents, teachers, and peers).

MOVING UP THE DOUBLE HELIX ONE RUNG AT A TIME

Click on the topic you want to jump to that section:

IMAGINAL REALM

IMAGE FORMATION

This is the beginning of what is from the beginning distinctly human consciousness: Freud considered the basis of image formation to be dream-work. The reason the model has the sun on the side of consciousness and the moon on the side of sub-consciousness is because human consciousness awakens and establishes itself with the circadian rhythm. To focus and concentrate requires a good night’s sleep (especially for an infant) and significant disruptions of the circadian rhythm are associated with health problems such as cancerous cell division (link).

Although the senses form within the womb, image formation occurs when the infant can experience things with the full array of senses to explore how a thing feels, smells, tastes, sounds and looks. In Spanish, the phrase for “giving birth” is “dar a luz”: “give to light,” thereby adding the most distal sense to the formation of images. Newborns are interested in things, but tend to be most interested in people. This is good because usually mothers provide what the infant needs: nourishment, cleaning, comfort and play. The infant’s focus on “savoring” is exemplified by the importance of mother’s milk (as Pope Francis has reminded us).

Perhaps the hallmark of image formation is signaled by the “bright-eyed smile” the infant reflects back to a smiling mother, showing that the infant recognizes the mother and that the infant’s mirror neurons are functioning. It is significant that human eyes have white sclera that highlight the direction of pupil focus, thus allowing an observer to follow another person’s gaze. In this sense, the “bright-eyed smile” shows the mirror neuron reflex of registering direct eye contact with the mother. Human infants spend twice the amount of time as other primates in direct eye contact with their mothers (Michael Tomasello et al., 2007; “Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: The cooperative eye hypothesis. Journal of Human Evolution, 52, 314-20). As a result, infants develop the ability to attend to reality mutually with the mother; this developing mutual attention, along with the vocal/auditory system, results in the acquisition of language.

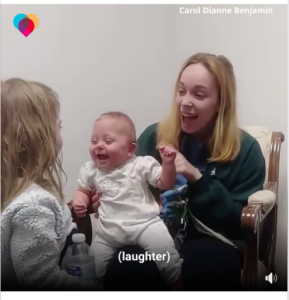

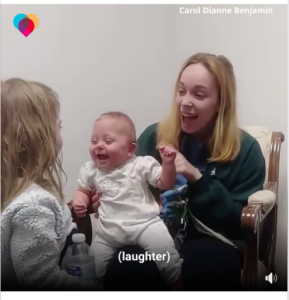

The auditory system is significant from the beginning, as can be observed from the experience of deaf children (see the gleeful reaction of a

Baby can hear, and baby laughs!

previously deaf infant to his mother after getting ear implants (link). Music is a human cultural universal, and the two most universal genres of music focus on the two ends of the life cycle: lullabies comfort the newborn while laments comfort those left with the loss of life. Lullabies not only comfort the newborn, but also the mother and fetus in the womb, supporting healthy fetal development. Lulling the baby into slumber helps establish the important circadian rhythm that leads to the alert “bright eyed smile” that helps cement the mother-infant bond. On the other hand, stress hormones transmitted from the mother to the fetus can inhibit the child’s long-term abilities to manage anxiety.

Music plays an essential role in healthy development and musical analogies permeate our lives. The mother’s “attunement” to the infant paves the way for the infant’s attachment to the mother. Throughout our lives we say that ideas and relationships that are near and dear to us “resonate” with us. Music helps us sustain our work effort (work songs) and the musical metrics of poetry made possible the oral history and transmission of core cultural narratives called epic poems (Homer’s and Moses’ stories were memorized before being written down). Romancing is done with a flute or harp and maybe singing, making it significant in mate selection. These things, along with the infant getting a good night sleep aided by lullabies, show that the theory that music plays no essential survival or evolutionary role (Steven Pinker) is tone deaf. The only way to maintain such a ridiculous theory is by separating music from all the other cultural functions it shares (dancing, poetry, story-telling, and the tradition of cooking and eating around the fire while the community celebrates the exploits of the day). Additionally, “research has confirmed the brain’s link for words and music” (link), and that “to your brain, music is as enjoyable as sex” (link). Prior to the full-blow conversation is the musical duet of infant musical imitation, mimicking both tone, cadence, and emphasis with calls and gestures that combine to form an inter-generational jam session (link). Charles Darwin himself bemoaned his loss of appreciation for music and poetry and how immersion in abstract formulae stunted his intellectual curiosity:

My mind has changed during the last twenty or thirty years… Now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry… I have also almost lost any taste for pictures or music… My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts…

If I had to live my life again I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week… The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature. The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, Norton 1993 (pp. 138-139)

Academics and scientists tend to like the Far Side cartoons due to the odd ways the panels depict concepts. Here we have a bear telling the young ones about an exploit involving hunters. Although they are not sitting around a fire as pre-historic humans did while they cooked food (bears eat humans raw), other elements of story-telling around the fire are present in this depiction.

Academics and scientists tend to like the Far Side cartoons due to the odd ways the panels depict concepts. Here we have a bear telling the young ones about an exploit involving hunters. Although they are not sitting around a fire as pre-historic humans did while they cooked food (bears eat humans raw), other elements of story-telling around the fire are present in this depiction.

Two other significant features of very young infants have to do with imitation and turn-taking. From very early on, infants will imitate sticking the tongue out (the tongue is a prominent feature even for very young eyes). This shows that imitation is hard-wired into human neurology. The second is that young infants tend to become subdued when mother provides face-to-face stimulation, but when mother becomes subdued, the infant tends to become more active. This establishes a template for later conversations using words (Bruner, Garvey). Communicatively, the infant cries when distressed, but doesn’t yet have any control over how she cries, leaving it to mother to interpret the cause of distress.

So the infant is now regulated by the circadian rhythm, her bright-eyed smile has cemented the bond with her mother, and her eyes are developing so that she can focus on distant objects.

The double helix model is a bi-lateral model, and we will see bi-lateral developments associated with different stages and steps. At first, the infant is using her two ears to locate sources of sounds and her two eyes to start to see figures three-dimensionally. There is not yet any eye-hand or hand-hand coordination.

IMAGE COMPARISON

Five month old baby Lucas has just been baptized. At the reception afterwards, family and friends stand around the dinner table as Lucas is held up by his grandmother facing out to the audience. First, the nearest person to his right gains his attention by waving and smiling in the goofy way that people naturally do. Lucas’s face flutters as he makes the effort to focus, aided by the attention getting antics of the audience member. Once he succeeds at focussing, his eyes coordinate and get bright with the resultant smile. With implicit understanding, the rest of the audience falls into the game with the next person waving and smiling, his face fluttering until, bingo! the bright-eyed smile. He did this about a dozen times, ending with the person on his immediate left. A perfectly orchestrated developmental tour-de-force! [6/22/14] (Family Study, 2015 link)

To achieve the distance focus in the story above, the infant’s eyes must develop where the photoreceptors flow toward the center of the eye to create a fovea (Newsweek, Your Baby’s Brain, pg. 21). In the story above, Lucas must see the waving hand and the exaggerated smile before being able to target the eyes, make eye-contact, which then produces the bright-eyed smile.

So Lucas is able to connect one moment to the next moment, and so on, guided by the orchestrating adults. The other thing infants can do at this stage is to look at one thing, then look at another thing, and then look back at the first thing (Piaget). Infants are starting to map out their surrounding; location, location, location. Infants are also not completely immersed in the moment and have made their first time distinction: “now” and “not-now,” or “now” and “then.”

Looking at one thing, then another, and then back to the first thing also provides the developing infant her first method of self-regulation: when a stimulus becomes overwhelming, the infant can look away to avoid getting over-stimulated, and then when composed, can look back at the stimulating object (person, pet).

IMAGE RELATION

I was at Beers Books on Father’s Day with a friend. A father was pushing a pram through the aisles with Junior inside who was looking directly back at dad. Dad was obviously wanting some adult conversation and it soon became apparent why. Junior was looking out from under the open sun canopy, staring at dad without smiling. Dad reported that Junior is 8 months old and when asked he explained that Junior was not crawling or toddling yet because he was too large to get up enough effort, so he wanted to be pushed around to see the sights. Dad would put the canopy down hoping Junior would calm down and sleep, but as soon as Dad did so, Junior batted it or kicked it up so he could see. The canopy was in the way so Junior would dispose of it with a quick punch or kick motion. Dad referred to this as Junior’s “big trick.”

Here we see the kind of goal directed behavior that Piaget refers to as the stage of “secondary circular reactions.” Infants can now relate one object’s effect on another, such as when the infant uses a stick to move a toy. Socially, infants can get their mothers to do more specific things because the infant can vary the sound and the timing his cries while watching how mom responds. Volume can be adjusted to make sure mother can hear. Crying gets mixed in with fussing and other baby vocalizations.

These abilities show that the infant has gained a sense of three dimensional time, where something she has grabbed then gets used to move something else. “Grabbed” becomes past while “using” is the present in the anticipation of the movement of the other object. This involves eye-hand coordination (the infant will no longer grab one hand with the other as if the hand grabbed were not part of his body — just like baby cats will chase their own tails).

The infant’s abilities to locate familiar objects in familiar places also develops so that the infant can tell when a familiar object has been moved to an unusual place. She can also track the movement of objects and people, even when they are temporarily hidden.

But the infant still needs to have things at hand or for them to be brought to him — he is not yet crawling or toddling. In pursuit of distant or absent objects or people, the infant will come to realize his own agency. Frustrated that the world cannot always spoon feed him, he will start getting along and getting up to go get it himself. Eye-hand coordination prepares the baby to start locomotion, the bi-lateral skills of moving arms and legs in coordinated ways to get from one place to the other. Thus we come to agent formation, toddling, and vocalizations called “performatives” that go with request and demand gestures to enrich the infant’s communication with the caregiver.

Sphere of Agency

AGENT FORMATION

We now enter the “motor” phase of Piaget’s “sensori-motor operations.” In the double-helix model, this is when the infant becomes conscious and learns about the self as an agent, an entity able to act.

Agent formation is motivated by the infant’s boredom with what is at hand and interest in things distant or hidden. To get at these interesting but ungraspable things, people and experiences, the infant must either get to them herself or find communication means to enlist others to provide the desired proximity.

Infants not only explore what their bodies and their vocalizations can do, the two are often combined in communicative gestures called “performatives.” Technically speaking, a “performative” is a vocal ritual that accompanies gestures. Performatives develop in the context of caregiver “game formats” such as “peek-a-boo” and “what’s this?”, games that are often used by mothers well before the infant can actively engage in them (much less understand the referential meaning of lexical items). In this way, infants are primed by familiarity of game aspects such as turn-taking, ritual and imitation which lead up to the toddler’s eventual use of language (Bruner, 1983, chapter 3).

A well-documented development of this phase involves “stranger wariness” and “separation anxiety.” Both involve a realization that the mother is a separate agent who is necessary to help the infant manage distress. The infant becomes wary of strangers who act too familiar without the reassuring mediation of the mother, while at the same time the infant uses the mother as a safe base from which to explore the unfamiliar (assuming that healthy attachment has been established).

The infant’s major task of being aware of the self as an agent is learning to walk. For some children, toddler-hood begins with crawling, followed by attempts to get up on the feet. For those who by-pass crawling, thrusting the body up on the feet, assisted by either an adult or by leaning against something, is the “first step” to walking. The infant has yet to gain balance or to know how to put “one foot in front of the other,” so first steps are either maintained by adult “sky-hooks” (similar to how adults help children learn to balance a bicycle) or result in a bounce on the bum.

The infant’s awareness of others as agents has a similar primitive quality at this age. Before, when the infant wanted something, he just looked at it and whimpered. Now he whimpers and looks to mother for assistance. He realizes he has to appeal to her for the object to magically appear. He is also learning to go beyond eye-contact and find out what mother is looking at so as to establish mutual attention. Using the unique quality of the human eye, he can follow the direction of her gaze so that he can participate in what she is attending to. This ability to develop mutual attention is crucial for later language development. Bruner describes in detail the way mothers initiate infants into repetitive games such as “peek-a-boo” and “what’s this?” to provide a format in which children can increasingly participate (become “agents” in the game rather than just “experiencers” of the game; Bruner, pg. 56) to the point of creating their own lexical items.

AGENT COMPARISON

This stage has the character of repetition. Physically the toddler is toddling, taking one step at a time, using the arms not to help balance but to break a fall — hence the unsteady quality of the operation. The toddler’s uncertainty keeps her eyes on her feet rather than where she is going, and often needs props such as chairs or adults to keep standing and moving.

Communication also has a shaky two step quality. To get help from mother, the toddler is aware that he needs to both get her attention and specify what he wants with conventionalized gestures and vocalizations. But these two functions are not well coordinated as yet. And while trying to figure out what mother is focusing on, if he is not successful in following her gaze the first time, he will return to her face to try to follow her gaze a second time (Bruner, pg. 74).

AGENT RELATION

If the infant’s sense of agency is first primitive and then erratic, it now becomes coordinated and organized. The toddler becomes a walker when she uses her arms for counter-balancing the legs rather than shielding an impending fall. And she can now coordinate gestures and vocalizations to better get mom’s attention where she wants it. And in ritualized games like “peek-a-boo,” the infant now can be a full participant with inter-changeable roles, everything short of using words symbolically (vocalizations are still imitations of sounds used ritually in the game sequence rather than symbolic referents).

The “relation” quality of this stage can be seen clearly in what the literature calls “give-and-take reciprocity.” Children learn that roles are reversible and reciprocal such as when one takes what someone has given and then turns around to give what was taken (going from being a taker to a possessor to a giver). Sometimes a gift is a material benefit and sometimes it is a symbolic act where the giving is the focus more than the gift itself. So children are initiated into give-and-take games such as rolling a ball back and forth — the object is not to keep the ball, but to send it back to its previous possessor. Here is how an extended family member or family friend can engage the 11 to 15 month old:

First, you want to make sure Junior understands that Uncle is a trusted family member and won’t over-stimulate him. Junior then sees that Uncle is delighted with a ball as he sits on the floor, creating a desire in Junior to get the ball himself. Uncle rolls the ball to Junior who then picks it up. Well, it’s just a boring ball, so now what? Well, Uncle seems very interested in getting the ball back. If Junior doesn’t catch on yet, Uncle may need to gently dislodge the ball from Junior’s grasp. At the point at which Junior might get upset, he finds the ball immediately rolling back to him. A little prompting from Uncle may still be necessary, but if Junior is ready to learn, he will find that “playing ball” is more interesting than “having ball.”

During this time parents are typically “bathing” their infants in language. The infant’s developed sense of agency is primed to take on words as communication tools once these ritualized “proto-conversations” are established. Once the infant makes the symbolic connection, she is no longer an “en-fant” (French meaning “without speech”), and has been drawn in to the world as a symbolic realm.

SYMBOLICAL REALM

SYMBOL FORMATION

“Uttering a word is like striking a note on the keyboard of the imagination.” — Ludwig Wittgenstein

Now is the time for the child to “stand and deliver.” As she identifies, distinguishes and uses lexical items, she can drop the gestural accompaniments of “performatives” and experience the power of words.

Science tends to rely on numbers and mathematics to establish “quantitative” truth, and as a result tends to downplay the significance of language: words are “qualities.” But all numbers are words, but not all words are numbers. Without language, math and science would not exist in consciousness. Numbers come into consciousness as a result of narratives, but narratives do not come into consciousness as a result of numbers (this is not to say that mathematical formulas are irrelevant to narratives; as with relativity, they can inform their own narratives).

Scientists often compete to be “hard-headed realists,” eschewing what are considered “sentimental” subjects such as poetry. But without sentimentality we wouldn’t have babies to become children whom parents expect to learn to talk as their first contribution to being part of the family and community.

There are things beyond language probably more significant than language, but we know of them because of language, not in spite of language. In other words, this website will be taking the significance of language development very seriously. To understand the child’s experience, it would be silly not to. And a “good” scientist would never want to be silly, eh? [irony intended] Or, as Wittgenstein has observed, “Never stay up on the barren heights of cleverness, but come down into the green valleys of silliness.”

Or, more generally, “If people never did silly things nothing intelligent would ever get done.” (Wittgenstein)

So let’s get down to the serious business of playing with the idea of language.

Learning to talk is a very emotional process. We can see this most clearly when there is a major failure to learn language, followed by its remedy. This process is revealed in the story told by Susan Schaller, teacher of sign language (which shares the same brain region as spoken language) in her book, A Man Without Words (UC Press, 1995). Schaller tells the story of Ildefonso, a deaf man who never was taught sign language until she helped him learn, requiring an arduous and ultimately creative effort. His experience of life before he learned language was similar to the “no-world” that Helen Keller described before she learned language at age seven. The relief both felt when language brought them out of their solitude shows the central role of language acquisition on development.

Does language spring upon us, or does it slowly and imperceptibly sneak up through the babblings and performatives of the infant? The “birth of language” has been shrouded in the mists of time and the clutter of everyday family life. This has led to many fine researchers to throw up their hands and enlist the relativist cliche, as Elizabeth Bates (1976, pg. 72) does here:

Anthropology recognizes that man has no birthday; zoology recognizes that life has no birthday; physics recognizes that matter has no birthday. The murky line between life and non-life, man and non-man, matter and non-matter stems from the fact…that we can recognize what, for example, is definitely at either end of a conceptual continuum…the transition from one to the other is continuous and not discrete.

While she concludes this, she also subscribes to Piaget’s assumption that language is secondary to symbolization, and that the cognitive symbol forms the basis of the linguistic social label for the symbol. The symbol is the “body”, the word the “costume” designed to “display” the symbol outside the mind.

Vygotsky, and Bruner in his stead, criticised Piaget on that score, showing how language is acquired in social interactions, with the language ability and the symbolic ability being one and the same. If language and symbolization are “born” in social interaction, is it something we can see? It turns out that yes, we can see (and hear) it, especially with the aid of modern technology. In the March 2011 TED Talk, “The Birth of a Word”, MIT researcher Deb Roy presented some findings from 90,000 hours of home video he took over the course of three years in all the rooms of their family house (excluding private areas). He sought to detail the influence of social environments on language acquisition, and ended up tracking 7 million words of home transcripts. The most significant findings are contained in the following transcript of the TED Talk (link):

05:46

So he didn’t just learn water. Over the course of the 24 months, the first two years that we really focused on, this is a map of every word he learned in chronological order. And because we have full transcripts, we’ve identified each of the 503 words that he learned to produce by his second birthday. He was an early talker. And so we started to analyze why. Why were certain words born before others? This is one of the first results that came out of our study a little over a year ago that really surprised us. The way to interpret this apparently simple graph is, on the vertical is an indication of how complex caregiver utterances are based on the length of utterances. And the [horizontal] axis is time.

06:31

And all of the data, we aligned based on the following idea: Every time my son would learn a word, we would trace back and look at all of the language he heard that contained that word. And we would plot the relative length of the utterances. And what we found was this curious phenomena, that caregiver speech would systematically dip to a minimum, making language as simple as possible, and then slowly ascend back up in complexity. And the amazing thing was that bounce, that dip, lined up almost precisely with when each word was born — word after word, systematically. So it appears that all three primary caregivers — myself, my wife and our nanny — were systematically and, I would think, subconsciously restructuring our language to meet him at the birth of a word and bring him gently into more complex language. And the implications of this — there are many, but one I just want to point out, is that there must be amazing feedback loops. Of course, my son is learning from his linguistic environment, but the environment is learning from him. That environment, people, are in these tight feedback loops and creating a kind of scaffolding that has not been noticed until now.

When Deb Roy says that caregivers “create a kind of scaffolding that has not been noticed until now”, he seems unaware of the work of Vygotsky and Bruner. Bruner says the same thing when defining “fine tuning”: “Parents speak at the level where their children can comprehend them and move ahead with remarkable sensitivity to their child’s progress.” (1983, pg. 38) Bruner also supplemented Vygotsky’s term “scaffolding” with his concept of the “format”: “A format is a standardized, initially microcosmic interaction pattern between an adult and an infant that contains demarcated roles that eventually become reversible.” (pp. 120-1) Examples include “peek-a-boo”, its older sibling “hide-and-seek”, picture book reading (“What’s this? It’s a…”), greetings and departures (“Say bye-bye!”). etc.

Now that we have explored the heart of symbol formation in the inspiration of language acquisition, we can move to the details of the development of declarative sentences and simple narratives of young children, before language becomes internalized and polite forms develop. But first, a word of advice for parents and teachers of young children from my 35 years of family therapy practice: Just as you don’t want your child yelling to get his way, you also don’t him whining to get his way. Whining regresses the child from language competent requests to infantile demands, and goes against what Bruner calls the “felicity” conditions of language acquisition, which is a way to say that when mom’s not happy, nobody’s happy. Which is why parents and teachers should train the child more on appropriate delivery than correct for grammar or diction (which they naturally do, unless they are training in the grammar police academy).

Now that she is a walker and a talker, the child is ready to take off in both the world, and the world of language (for a great depiction of the walking toddlers new perspective on the world, see this Air BnB Ad). But before she moves on from being a walker to becoming a runner, she picks up dancing. It may be necessary for children to practice different leg, hip and arm movements to attain the required balance to run without crashing. (Again, music takes its place nudging the newbie walker into a full-fledged runner.)

This children’s music cd cover shows children in various states of toddling and dancing. Below shows how dance therapy can help children learn how to control themselves better:

SYMBOL COMPARISON

Not only does the advent of language play a central role in human development, it also irreversibly alters the brain. By the end of symbol formation, the child has acquired the basic building block of “the neural lyre of poetic meter” (Turner & Poppel, The Neural Lyre: Poetic Meter, the Brain, and Time, Poetry, vol. 142, no. 5, Aug. 1983). Of poetic meter, Turner and Poppel say:

This fundamental unit is nearly always a rhythmic, semantic, and syntactical unit, as well: a sentence, a colon, a clause or a phrase; or a completed group of them. Thus other linguistic rhythms are entrained to the basic acoustic rhythm, producing the pleasing sensation of “fit” and inevitability which is part of the delight of verse, and is so helpful to the memory. Generally a short line is used to deal with light subjects, while the long line is reserved for epic or tragic matters. (pg. 288)

To sum up the general argument of this essay: metered poetry is a cultural universal, and its salient feature, the three-second LINE, is tuned to the three-second present moment of the auditory information-processing system. By means of metrical variation, the musical and pictorial powers of the right brain are enlisted by meter to cooperate with the linguistic powers of the left; and by auditory driving effects, the lower levels of the nervous system are stimulated in such a way as to reinforce the cognitive functions of the poem, to improve the memory, and to promote physiological and social harmony. Metered poetry may play an important part in developing our more subtle understandings of time, and may thus act as a technique to concentrate and reinforce our uniquely human tendency to make sense of the world in terms of values like truth, beauty, and goodness. Meter breaks the confinement of linguistic expression and appreciation within two small regions of the left temporal lobe and brings to bear the energies of the whole brain. (pg. 306)

The fit of the three-second meter with children’s developing neurology helps explain the often noted “ritualistic” characteristic of two year-olds who will adamantly correct a parent’s re-telling of a story if anything is changed, or who won’t go to bed without every step of the “going to bed” ritual being completed in proper order. Metered poetry’s effectiveness at aiding memory is how human oral traditions have thrived over the centuries, and why music helps with memorizing sets like the alphabet song (6 verses ending with “mother aren’t you proud of me!”: of course, children at this age don’t understand the alphabet yet as a written code, but can memorize the song and enjoy it).

Once children produce enough simple sentences, their vocabulary starts to explode, and they start piling sentences on top of each other using the simple conjunction “and”. In terms of narrative development (Applebee), this moves the child from unjoined “heaps” to conjoined “sequences.” An example of this in a basic child narrative might look something like this: “The boy is lost and he is hungry and then he got found and eats dinner and goes to bed.”

So here are some characteristics of the “terrible twos”: run-on sentences and running out into traffic! Parents often use a method to “herd” their run-away two-year-old with the game of “chase” (as one mother told me of her relationship with her 2 year-old, “we love to be chased”):

A mother in the park was with her 2 year-old; he was mock-running-away, looking over his shoulder and giggling uncontrollably, as his mother ambled after him, mock-threatening “I’m going to get you! I”m going to get you!” Then, as she closed in on him, she swooshed her arms around his torso, and spun him around as she exclaimed: “Wheee!”

Experiences like this explain why many young boys want to marry their mothers.

In terms of temporal distinctions, symbol comparison encodes the sensor-motor distinctions that occurred during image and agent developments. With symbol comparison, the now/not now distinction is encoded, in the form of now and then (past). This is when children learning English over-generalize the -ed ending marking past tense (e.g. “swimmed” for “swam”). It won’t be until the child has achieved symbol relation that the past/present/future distinctions are fully encoded.

Linguistic conjunctions allow children to verbalize two-step communications: if the child needs mom’s help, he can first use language to get her attention (“mommy, come here”) and then to direct her attention (“gimme bear” when bear is out of reach).

Another linguistic development that helps two-year-olds accelerate their speech production is the development of pronouns. During symbol formation, young children use names — they learn that everything has a name — but now they start shortening those nouns with pronouns. “I” and “you” are first to develop, then third person pronouns (“he”, “she”, etc.). At this stage, children can only handle a single substitution of a noun into a pronoun in a sentence (e.g. “I give the ball to mommy” rather than “I give it to you.”); it won’t be until the next stage that multiple pronouns can be substituted. There is a parallel in pretend play where children at this stage can substitute one pretend item to facilitate the play, but cannot yet substitute two items.

These development give the child’s language production a quality of uncoordinated and headlong compulsion, as though the child’s tongue is stuck on the accelerator and obstacles are dealt with by piling on more language at greater speed and higher volume. Until children can take their tongue off the accelerator and eventually apply the brake, the more social children tend to be more aggressive until the means of self-control are at hand.

SYMBOL RELATION

1-2-3 Go

1-2-3 Go — Going

1-2-3 Going

1-2-3 Going…etc., etc.

Sample from Pilot Study, 1983

Counting to three becomes prevalent as children approach their third birthday. In the sample above, a boy almost three years old, used this chant , rocking back and forth, while waiting in the back of his father’s pick-up truck (as if to get the truck going by pushing it forward). Notice the shift from the present indicative (go) to the infinitive (going). The boy uses the 1-2-3 rhythm as a cue for the wait —> release pattern of his rocking — while holding on to the tailgate, he lunges forward on the count of 3.

In our culture, the child’s third birthday makes this ability to count relevant to encoding time distinctions: he begins to understand “I was 2, now I’m 3, and I will be 4.”

In the above example, the boy is using his chant to help him wait until his father is ready to go. Children at this stage can wait when told to, but can’t wait on their own accord. This example demonstrates two aspects of language for the 3 year old: first, he can take his tongue off the accelerator and stop aggressively pestering his father, and he can use language to entertain himself while he waits. When psycholinguists examine the functions of speech, particularly “private speech”, they tend to neglect the fact that children love to play with language.

Two important conjunctions children learn here are “but” and “because” (Bates). These are important because they allow children to verbalize conflict, which is a first step towards learning how to resolve conflict. We intuitively know the difference between “and” and “but” — we see this when we prompt someone to complete a sentence. For instance, if a friend says “Harry wanted to go to the store…”, and then stops, if the partial sentence ends with lowering intonation, we are likely to say “and?”, which may prompt the completion of “and he borrowed my car.” But if the partial sentence ends with rising intonation, we are cued that for some reason the intended action was not completed, and we are likely to prompt with “but?”, which may prompt the completion of “but he didn’t have any money.”

In this way children can better communicate with parents about what is wrong. These findings are in line with Applebee’s description of children’s “primitive narratives” at this stage.

Another linguistic development among 3 year-olds is the subordinate clause. This allows the child to go from two sentences like “the horse was tiny” and “the horse struggled up the hill” to “The horse, who was tiny, struggled up the hill.” (and eventually to “the tiny horse struggled…”) Patricia Greenfield (The Development of Rule-bound Strategies for Manipulating Seriated Cups: A Parallel Between Action and Grammar, Cognitive Psychology, 3, 291-310, 1972) found an interesting parallel between action and grammar on a task of “nesting” seriated cups. She finds that children develop through three strategies for successfully seriating the cups that parallel the stages of symbol formation, comparison, and relation. At first children need to understand that they can’t put any cups in any others if they first pick up the largest cup. After they figure that out, they can then pile a number of smaller cups inside the largest (and another, and another). At the end, when they can produce subordinated (“embedded”) clauses, they can also seriate a cup in the middle of the series when given it after having seriated the others.

These parallels between action and grammar should not surprise us since Applebee’s definitions of narrative structures came from a sorting exercise Vygotsky developed.

So all-in-all, the child at this stage is much more coordinated than the 2 year-old, but he still cannot be trusted alone because he has yet to develop the self-regulation that comes with the internalization of speech.

Sphere of Subjectivity

SUBJECT FORMATION

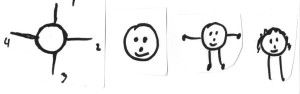

With this new sphere of experience, the child is thrown back on herself in confusion as she realizes that her experience is subjective, or “internal” and private, as is the experience of others. The “interior” nature of subjectivity is reflected in children’s drawings at this stage. 3 year-olds can do circles and lines and crosses. 4 year-olds can form a radial, where spokes come out from a center point. Here is when we see children producing suns with rays emanating out, or sunflowers, with happy faces. This is the beginning of the stick figure, which first has arms and legs coming out of its round head — later, a torso gets added with arms and legs coming out from the torso. (Rhonda Kellog, Understanding Children’s Art, Psychology Today, 1967, 1, 16-25) Children’s imagination now makes them less interested in stories about the familiar world and more interested in strange worlds they can master from a distance (Applebee, pg. 75). Imaginary friends can help children learn social expectations and limits (Brazelton, Imaginary Friends Help Kids Develop, SF Chronicle, 11-17-1992, D4).

But before we go down this rabbit-hole, a few words on how we got here that were not covered in the last section.

In 1968, Kohlberg wrote an article on the issues of “private speech” and its relation to the internalization of language. “Private speech ” are the verbalizations of children that occur while they are alone or when they do not seem to be considering the response or understanding of others present. His researches concluded that private speech is not exclusively egocentric as Piaget contended, and that it did play a role leading to the internalization of language. He especially singled out “mumbling” as a clear predecessor to internal dialogue.

This is an interesting finding, but a rather narrow one given the range of speech behavior exhibited by 3 year-olds. For instance, during my MSW thesis participant-observer pilot project, I was able to observe and elicit a range of verbal behaviors from two research subjects who were neighborhood children in family student housing at UC Berkeley. One was a 3 year-old girl, I will name Sydney, who was rather soft-spoken. In the housing complex, which was former WWII ship-builder housing, our married studio unit was up-stairs and next door to a one-bedroom family unit in which the subject family resided. When Sydney was on the up-stairs balcony and her mother was in sight down below, Sydney had to make a special effort to yell loud enough for her mother to hear. Conversely, when she was sitting right next to her mother, she would share something in a whisper, obviously making sure her mother could hear but others couldn’t. This volume control leads children to realize that when they are speaking to themselves, they can be quieter than a whisper — indeed not vibrating the vocal cords at all (not even a mumble).

These findings are reinforced by research on “sub-vocalizations” and auditory hallucinations. “Sub-vocalizations” are when the vocal tract is muscularly engaged, but the vocal cords are not. This may be because when we are thinking rather than speaking the words, we are still imagining saying them. So when researchers found that psychotic patients experiencing auditory hallucinations were sub-vocalizing at the same time, it suggests that their sub-vocalizations have become dis-associated from their sense of agency, and they experience the thoughts as coming from outside themselves (Louis Gould, Verbal Hallucinations and Activity of Vocal Musculature, American Journal of Psychiatry, 105, Nov. 1948, pp. 367-72). This was further reinforced by the finding that auditory hallucinations can be interrupted by having the subject hum a song. I used this technique to great benefit with a psychotic teenager who loved his new ability to banish the voices he didn’t like. He was quickly able to sub-vocalize his humming so that the disruption of his voices didn’t make him appear “crazy.”

Further collaboration of these findings comes from a study showing that 4 and 5 year-old children recall items better when they subvocalize while learning the items and while they wait to recall them (internal rehearsing). (Linda Garrity, An Electromyographical Study of Subvocal Speech and Recall in Preschool Children, Developmental Psychology, 1975, Vol. 11, no. 3, 274-281) This suggests that the internalization of speech is not only a sign of development, but is also a driver of development during this period.

“Confusion” at this point in development (following the “inspiration” of the symbolical realm) means the fusion of mind and body, as evidenced by blushing (Bhuwan Joshi, personal communication). Shame and the development of modesty and politeness are the hallmarks of this phase. Whereas the two year old will thrillingly shed his clothes to nakedness and balk at being clothed by parents, the three year old is helping to have clothes put on, and the four year old is learning how to clothe himself. Typically 3 1/2 is the time when children are most “potty-mouthed” with their language, and struggling with toilet training. The cooperative and coordinated homeostasis of the 3 year-old becomes disrupted by the nearly 4 year-old’s self-consciousness, resulting in often strained relations with peers and adults.

In the mental health field, the experience of shame is associated with some controversy (one does not want to spend one’s life “in shame”). In my perspective, there is a marked difference between “humility” (as a virtue) and “humiliation” (as an abusive practice). Along these lines, I agree with the Canadian philosopher and anthropologist of everyday life Margaret Visser (The Gift of Thanks, 2009) who points out that the opposite of shame is not pride, but shamelessness. To best understand this term, it helps to know Spanish, where the term “sinverguenza” is a well-defined character-type that is best well-avoided in life. Attached to a “sinverguenza” for long, one will live a life of continual grief if not devastating scandals, embarrassments, and other calamities.

When we look at the more mental side of the child, we see that 3 1/2 year-olds can say honestly “I don’t know”, showing their initial understanding of mental verbs similar to “know.” Aside from “know”, other mental verbs start to rear their heads, such as “dream”, “think”, “imagine”, and “guess.” Over the course of this period of development, children learn how to sort out these mental verbs, such as to “know” should mean more than to “think” or “guess”, and that to “dream” or “imagine” are altogether different things. More committed mental verbs, such as “plan” or “promise” are not yet within the young child’s grasp. At this stage, the child understands a difference between “know” and “think” which is that “knowing something” means it is true, whereas “thinking something” might not be true (Johnson & Maratsos, Early Comprehension of Mental Verbs: Think and Know, Child Development, 1977, 48, 1743-1747).

So the child’s mental and social worlds have been disrupted, he knows that the world is expecting that he control himself more, and he is entering the social world of peers outside his family. He is increasingly expected to be potty trained, to clothe himself, and to be patient and polite. He deals with it, but not very well at first. He knows when he is being polite, but misidentifies how he does it, generally underestimating how polite he is being (what Bates calls “Minus Polite”). Similarly, children make mistakes copying a hierarchical tree structure (“mobile” shape; see illustration below right) — whereas at 3 years-old, they can accurately copy part of the structure without realizing it isn’t the whole structure, 4 year-olds make a more complex structure, but with obvious errors that they are unable yet to track (Greenfield, Building a Tree Structure: The Development of Hierarchical Complexity and Interrupted Strategies in Children’s Construction Activity, Developmental Psychology, 1977, vol. 13, no. 4, 299-313). In general, the child’s functioning can be characterized by Applebee’s description of children’s narratives at this stage as “unfocussed chains.”

At 3 years-old, children have learned how to metaphorically take their foot off the gas pedal — now at this stage, children are learning how to apply the brake. It can be rough riding, and often children will skid in and still bump the person ahead of them, but this is the messy beginnings of “executive functioning” as in “Stop and Think.” Cognitive-behavioral researchers and therapists have found that at 3 1/2, children start to be able to follow directions to not do something, such as pressing a red button when it lights when the instructions were to press the green button when it lights and not press the red button when it lights (Meichenbaum & Goodman, Reflection-Impulsivity and Verbal Control of Motor Behavior, Child Development, 1969, 40, 785-797). Meichenbaum also found that impulsive children could be taught methods of self-talk to improve their patience and attention to detail (Meichenbaum & Goodman, Training Impulsive Children to Talk to Themselves: A Means of Developing Self-Control, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1971, vol. 77, no. 2, 115-126), methods that have been incorporated in best practices such as Aggression Replacement Training (Glick & Gibbs). See also the program I developed for Self Control Trainings on this website under Welcome to My Projects.

SUBJECT COMPARISON

Just as the “symbol comparison” stage is based on an “and, and, and” template, (propelling the story forward), so the “subject comparison” template is based on “why, why, why.” Children of 5 years old never tire of asking “why” to every answer to their previous question of “why.” In some instances, this is a sincere attempt to understand and find meaning in experiences; at other times it is an attempt to fore-stall the inevitable, the final reason being “Because I’m the Mommy.”

5 year-olds can do more than count their fingers, they can also appreciate the perception of age. My pilot study subject, Jason, was aware of age norms when he said “I’m in kindergarten but I’m still 4.” (5 being the stereotypical kinder age) Once I was with Jason and one of his neighborhood friends, Sonny. Being the researcher that I am, I had asked Sonny previously if he was 4 years-old, and he had said yes, but it turned out he was still 3 years-old.

Peter (to Sonny): “Why did you tell me you’re four?”

Sonny: (no response)

Jason: “Because I think he makes so that you’ll think he’s four.”

Differing perceptions mean a lot to 5 year-olds. Whereas the four year old considers hide-and-seek to be an interesting diversion, the five year old considers it an obsession (good skill for hunters!). At the previous level, she understands the basic idea of keeping a secret hidden, but is not very good at maintaining secrecy. Now at 5 years old, she is better at hiding, making sure nothing is sticking out in view (well, pretty much), and trying to keep totally quiet (suppressed giggles, no wiggling around). Similarly, five year-olds can keep a surprise a secret for far longer than 4 year-olds whose inhibitions break down fairly quickly to blurt out the secret.

My pilot study research subject, Jason, started his hide-and-seek career with me when he was about 4 1/2. On his first outing at hiding, when I started to approach the hiding region of the game, he said “I’m in the living-room — come and find me!” But as he approached five years old, his strategies of hiding and finding expanded considerably, but not yet as thorough as possible. Here is a full account of a complete game of hide-and-seek when Jason was nearly five years old:

Jason was the first to hide, which he did under the living room couch. He tried to be completely hidden and remain silent. The latter became difficult for him as I entered tromping like the jolly green giant, pronouncing “Where is Jason? Where could Jason BE?” As a result I heard the muffled snorts of a child trying not to laugh by holding his breath and smothering his mouth with his hands. A noble effort.

When it was my turn to hide, I used a method I had learned in my hiding career: if you want to keep someone anxious to find something from seeing it, put it above eye level. When anxious, people tend to not look up.

So I went into the bathroom and shimmied my way up, Spiderman style, into the upper bracket of the shower stall. True to form, when Jason investigated the bathroom, he didn’t look up and didn’t find me. After he left to investigate other rooms, I used the echo chamber effect of the small bathroom, aided by my hands forming a mega-phone, to pronounce “HE’S IN THE BATHROOM.” Jason responded by scampering into the bathroom and re-investigating the spots he had already examined. Again failing, he left to try his luck elsewhere.

Before giving up the game, I spontaneously decided on one more trial, and mega-phoned out: “HE’S IN THE TOILET!” Jason rushed in and lifted the toilet seat. Fortunately he found nothing there but clean water. I realized at that point that I had broken down his reality testing and it was time to give up the game so as not to traumatize him. I revealed my hiding spot and we had a good laugh.

What we see here is not simple “egocentrism,” but earnest attempts to transcend egocentrism. Which leads to the next study where Jason demonstrates his understanding that thoughts are private:

At the time I had a 1966 Chevy in-line six-cylinder truck. Jason was with me when I changed the oil. There is a lot of space under the hood to see the engine and what I was doing. The session went as follows:

I open the hood, place the oil pan under the engine, remove the bolt to drain the oil (glug, glug, glug), remove the old oil filter and install a new one, replace the bolt, and pour in the new oil (glug, glug, glug). Then I put the hood back down.

I used this as a metaphor by asking Jason some questions:

“Jason, you know how I could open the hood of the truck and see how the engine works?”

“Yeah.”

“If I opened your head, could I see what you think?”

In response to this Jason went into a somewhat lengthy description of a scene from the recent Star Wars movie when a space ship penetrates into a hollowed-out planet. He was clearly following the metaphor, and I was being very patient, but I didn’t want to get side-tracked with another metaphor. So I persisted:

“Yes, but Jason, if I opened up your head, could I see what you think?” To which he responded:

“You have to guess until I tell you.”

“And if I did open your head?”

“Then I won’t be alive.”

“What would I see?”

“My engine?”

Obviously time to sew up that interview. Because of the trusting relationship, Jason took my questions both playfully and seriously without getting over-stimulated or scared, and no scar was left. But his response “Not until I tell you” has gained notoriety – as one of my clinical supervisors said, “Jason has better boundaries than most of my (adult) clients.”

Jason’s comprehension and use of “Not until” is important to understand what children that age are learning by way of frustration tolerance. Prior to this kind of impulse control, children understand that their requests/demands are met with “yes” or “no.” In this frame, a contingent yes is not understood (“not now, but later”), and is responded to as a “no” (eliciting either defeat or tantrum). Now children are learning that parents will grant contingent permission, with “first this, THEN that” (e.g. yes you can have dessert, but only after you finish dinner). Prior to the age 5 developments, children need this spelled out in order to not get upset — now parents can use the shortened “not until” phrasing with a chance their child will understand the contingency isn’t a categorical “no.”

In the more mundane world of “mobile construction,” children now perceive the mobile as two separate parts joined at the top, so they construct each side separately from the bottom up and then attach the two parts at the top (these structures are similar the Applebee’s “focussed chain” narratives). The results are more accurate than the 4 year-old versions, but the two sides aren’t reliably the same. Other areas where children struggle with accuracy are: perceptions of politeness, where children remember behaviors as more polite than they really are (“Plus Polite” — Bates); as well as children’s understanding of the mental verb “guess” where they assume that a “guess” is a wrong thought, assuming that guesses are never right. (Johnson & Wellman, Children’s Understanding of Mental Verbs: Remember, Know, and Guess, Child Development, 1980, 51, 1095-1102) Applebee describes narrative structures here as “focussed chains” in which the story line is held together by one constant feature, usually a character, but the plot is not fully developed and reversible.

SUBJECT RELATION