Preface

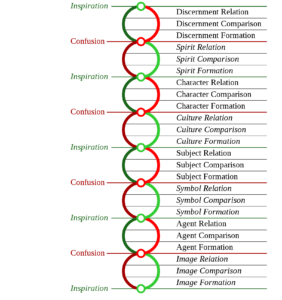

The field of developmental psychology seems to have concluded that if a finding is not found to be statistically significant, it is not relevant to the “science.” This would preclude inter-disciplinary approaches, such as those using philosophy, history, or single case studies. Contrary to this attitude, a meta-analysis has concluded that reading good fiction helps us understand others and be kinder people (link). Whenever I do research, I use the  double-helix method to balance non-fiction with fiction, and have a particular interest in literary non-fiction (see Weschler, XX). In that spirit, I venture to present some of my favorite fiction in terms of how it depicts developmental states.

double-helix method to balance non-fiction with fiction, and have a particular interest in literary non-fiction (see Weschler, XX). In that spirit, I venture to present some of my favorite fiction in terms of how it depicts developmental states.

This paper is based on the double-helix model of development, which is depicted here and explained in the Nutshell section of this website. I trace here the developments from Subject Relation (Calvin and Hobbes) through the Cultural Realm and the Sphere of Character up to Spirit Formation. The writing here is the most casual on this website due to the whimsical nature of a lot of the material.

As a Christian I do not believe in magic in the literal sense, but there are many Christian writers who use magic in imaginative ways. An example comes from the Dinotopia series written and illustrated by James Gurney. In The World Beneath (Harper, 1995) a “key” discovery is made when it is found that two ancient keys fit together to form a “spiral key” (one held by the male Arthur and the other held by the female Oriana). The half together form a double spiral, necessary to the completion of the story’s mission (pg. 29):

The model reads from the bottom up, with infant development in the lowest two rings, and spiritual development in the top two rings. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Jump To:

The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place

Introduction

One of the greatest literary achievements was the psychoanalytic discovery of the significance of dreams. Freud was not honored as a scientist so much as a literary artist, having been awarded the Goethe Prize (after the great German poet) in 1930. There is much controversy over the meaning of dreams, but one universal that Freud recognized was dreams of flying and falling. An interesting variation on these archetypal dreams is dreaming of gliding — gliding is more effortless than flying, and easier to land without crashing.

Flying and falling lend themselves not to just impulses and instincts, but to our general sense of well-being: flying is associated with elation and levity, whereas falling is associated with fear and gravity. Levity and gravity also associate with images of jumping and landing, and dancing as a way to bring levity to gravity. Levity and gravity are also associated with savoring skills and coping skills, being positive and being negative, comedy and tragedy.

Comedy and tragedy are plot devices that are inter-woven in the fabric of life. Every good writer knows this, and we learn it best from the best writers and teachers (see Georgette Heyer at the end of this article).

Research has found that people who enjoy literature tend to be more empathic than those who don’t. The simple explanation is that readers are trained by authors to understand the perspective of others. I have always found that reading good literature helps with my non-fiction writing. This is part of my binary approach (remember, two spiral strands are better than one!). [For evidence that left-handedness helps bi-lateral functioning and creativity, see here.]

Literature has been getting better and better, with the best authors these days having read the best authors of their youth. Now, in the wake of English Literature’s greats such as Jane Austen and P.G. Wodehouse, we have current masterpieces such as Lemony Snicket, How to Train Your Dragon, The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place, etc. So, for instance, The Incorrigible Children series is aptly described as Jane Eyre meets Lemony Snicket.

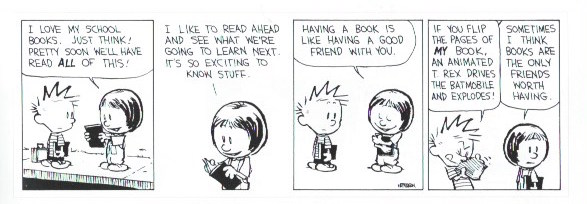

Susie trying to help Calvin understand that reading can help make friends. (10/14/93) In the same vein, macbooks.com’s motto is “Our books are friends for life.”

Various characters come to mind as we scan the developmental landscape. To display depictions of the age range from youngish child to youngish adult, I will be pasting together scenes and themes from Calvin & Hobbes (yes, the comic strip!), Bertie and Jeeves (yes, we’re getting too many males here, so…), Jane Eyre, and the Incorrigibles governess Penelope Lumley.

But before we venture into the literary world of childhood, I want to give an example of how fiction authors tend to value language more than scientists who hack it up and examine it to death. Literature does not tend to explore the advent of language in toddlerhood, but a fantasy book illustrates the power of speech. In Linnets and Valerians (Coward-McCann 1964), Elizabeth Goudge creates a character named “Daft Davie” who was put under a curse as a youth that rendered him unable to speak. After the curse gets lifted, he has this conversation with Uncle Ambrose (pg. 269):

“I fear you must think my questions impertinent,” said Uncle Ambrose.

“I am glad to answer them,” said Daft Davie, “for words taste like honey on a tongue that once was bound and now is free.”

Words taste like honey to someone who can’t take speaking for granted. Now let’s jump to the benighted childhood of Calvin who takes a lot for granted, which leads to the Hobbesian surprises that delight us all!

Calvin and Hobbes

Over the many years of Calvin’s madcap adventures with his stuffed tiger Hobbes it is generally assumed that Calvin is a stable 6 years old. The typical U.S. 6 year old does have many qualities in common with Calvin, especially his unbridled imagination (except when he runs up against reality in the forms of Hobbes, his parents, and Susie Derkins, the girl who just wants to be his friend, but not too much). With this imagination comes some gullibility, such as when Calvin’s father convinces Calvin that he came into the world on a “blue light special from K-Mart!“ (4/18/1987) The idea that Calvin is actually a gizmo freaks him out!

This cartoon should be enough to shame the scientists who believe we are nothing but mechanistic automatons. Henri Bergson defined humor as depicting the human as an automaton, making us laugh because we know it is not true! But Calvin is too young to know better.

But other qualities of Calvin are more typical of the 8 year-old boy. The 6 year-old with his imagination is more endearing (subject relation), whereas the 8 year-old with his “Boyz Only” Club is more annoying (culture comparison). Another quality more like an 8 year-old is his fixation on being able to perform the “daring-do” feats of Spaceman Spiff, and his intensely held gender identity that leads him to treat Susie Derkins like she has “cooties.” 6 year-old boys are not freaked out by the idea of “smooching” (e.g. the pre-schooler being seen hugging mom in public) but Calvin certainly is (typical of the school age boy)!

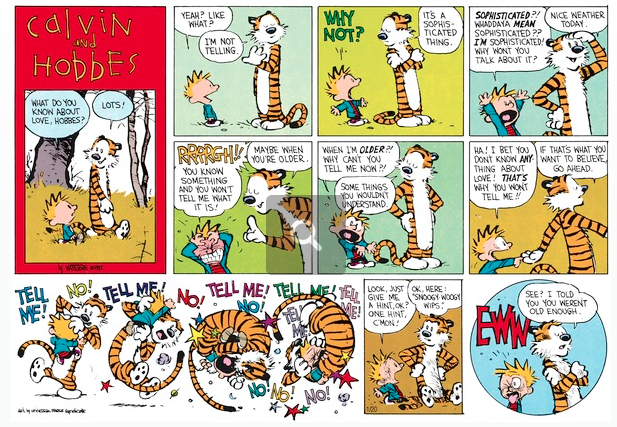

Talk about “smooching” is the main source of conflict between Calvin and Hobbes, with Hobbes often taunting Calvin with the idea (usually associated with Susie). Hobbes’ demeanor in this regard is more of the self-composed 14 year-old who knows how to act “cool” and “debonair” (character comparison). The gap between Calvin and Hobbes on this score cannot be bridged without resorting to a whole other comic strip where Calvin would no longer be Calvin and Hobbes would no longer exist — an eventuality suggested by Susie in this strip (11/18/1988):

Notice that Susie suggests that Calvin might have a different perspective on females when he is 17 years old and suggests that she doesn’t think it likely he will gain this sign of maturity sooner.

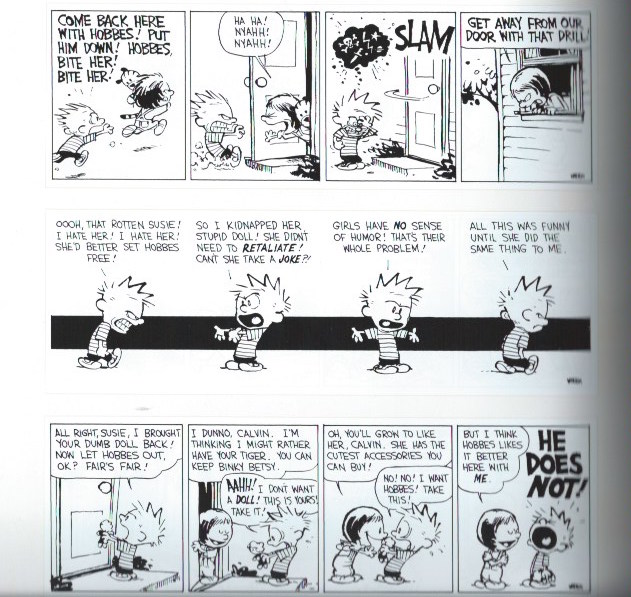

A good example of the difference between Calvin and Hobbes is a series of six strips where Calvin tries to get the better of Susie and Susie uses her charm with Hobbes to get the better of Calvin (9/2 to 9/8/1990):

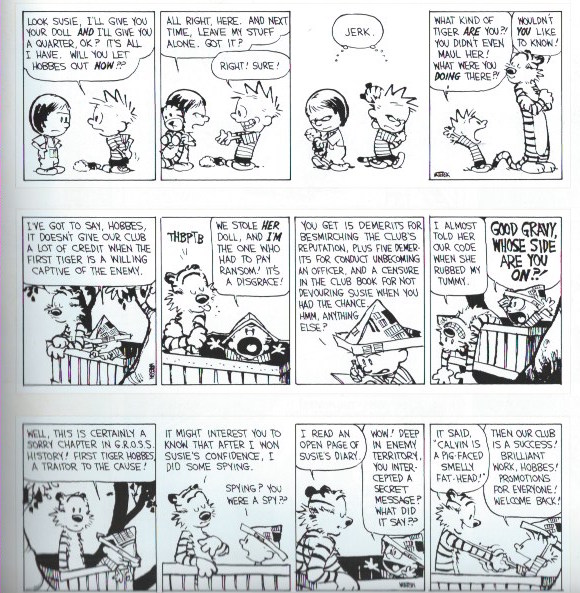

Finally, a full out fight between Calvin and Hobbes over Hobbes’ esoteric, and closely held, knowledge about “love” (3/8/1992):

Note the way Calvin and Hobbes look side-by-side. Typical of middle-school kids — some have shot up like sprouts, and others remain munchkins for considerably longer. Calvin is still “cute”, but he is getting too old to be cute while he’s still too young to be “cool.” Hobbes is still a little “gangly”, the puppy with the too-long legs, but he definitely has composure and “cool.” Calvin might not agree, or even understand, but Susie sure does!

[For a tribute to Calvin and Hobbes, focusing on the 6-year-old imagination, click here.]Bertie and Jeeves

Jeeves and Wooster played by Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie. As usual, Wooster looks perplexed while Jeeves looks “knowing.”

Next character to consider is Bertie Wooster, who, with his butler Jeeves, is a mainstay of English comic literature. One of the reasons why Jeeves and Wooster lasted so long as a comic duo was their Calvin and Hobbes quality of timelessness. Bertie is an upper-class “twit” who hasn’t matured much past Calvin, except that his imagination is more lazy (but not less active!) and he knows he’s a twit that can’t be expected to be taken seriously, rather than convincing himself that he’s a hero (like our hero Calvin!).

The plots of Bertie and Jeeves stories usually involve some romantic interest that threatens Bertie’s bachelor life to a gal who Bertie is either not ready for or who is ill-suited to Bertie. Since Bertie gets tangled up in the machinations of his various and prodigious aunts, who all want to get him hitched, it is up to Jeeves to provide the escape routes. This not only serves Bertie, but Jeeves as well, since once Bertie gets married it is assumed that Jeeves will have to go. Not what Jeeves wants.

This is where the comic duo would have left off if another author had not created a new script for the duo (authorized by the estate) called Jeeves and the Wedding Bells: An Homage to P.G. Wodehouse by Sebastian Faulks (St. Martin’s Press, 2013). In this sequel, Bertie is probably 30 years old or so, and is still clueless about his relationship with women. In this novel, Bertie spends a few weeks in the Spring in the south of France and hits the gay spots with a young woman he meets who he enjoys like a dear, vivacious sister. When they meet up later in unusual circumstances, Bertie becomes confused by her inexplicable behavior. As always, he seeks wisdom from Jeeves, who at first seems to Bertie to be speaking a foreign language:

“The second reason is a delicate one, sir. It raises questions of feelings contingent on your own person.”

“Would it be possible to speak in plain English, Jeeves? I’m in a spot of bother here.”

“I shall endeavor, sir, to…”Jeeves coughed.

“Would you like a glass of water?” I asked.

“No, sir, I…forgive me if this appears in some way ultra vires, but —“

“You’re at it again.”

“Very good, sir.” After one final throat clearance and wistful glance towards the grazing herbivores, he finally gave voice. “Had it occurred to you, sir, that Miss Meadows may entertain certain feelings for you?”

“Feelings? What sort of…good heavens, Jeeves, you don’t mean…Surely not…not that sort of feeling?”

I sat down heavily on the end of the bed. My emotions at this moment can best be described as confused. There was a bit of exhilaration, a hefty dose of doubt, a worry about Jeeves’s mental stability and the usual unease about bandying a woman’s name. When the roiling waters of the Wooster mind had calmed a fraction, however, there was only one thing visible: disbelief.

I chose my words with care. “What on earth makes you think that a woman who edits books and shoots the breeze with you about… what’s that chap’s name…Something-hour?”

“Schopenhauer, sir.”

“…and furthermore looks like an angel in human form on a quite exceptional day for angels would care for a complete ass like me — an ass, what’s more, she’s just seen manhandling her cousin?” (pg. 86)

Bertie finally experiences the confusion that comes with puberty — a late bloomer indeed! It takes him quite a bit of mucking about while Jeeves spins his uncanny webs of behind-the-scenes interventions to finally be ready to consider the need for intimacy in his life. This occurs near the end of the novel as Bertie continues to have to impersonate a valet (for complicated reasons we won’t go into here) while his butler, Jeeves, impersonates a Lord during their visit to someone else’s manor (yes, it’s complicated). This is when Bertie’s epiphany occurs:

Though dressed as a valet, I took the wheel of the two-seater as we left the Great Wen once more and headed for the sunlit hills. There is something about this particular road with its signs to Micheldever and Over Wallop that always seems to lift the spirits. The first bright green of May had given way to something lusher, so everything in the countryside looked just the way the Almighty must have roughed it out on his sketch pad; the cow-parsley could not have been more rampant, the oaks more oakish or the roadside inns more tempting if they’d tried.

“I say, Jeeves,” I said, waving an arm in the general direction of Stourhead, “it’s odd to think we might have lost all of this. During the…” I trailed off, not wanting to put a damper on things.

“The hostilities, do you mean, sir?”

“Yes. Do you think it will all ever just…disappear?”

“No, sir. ‘A thing of beauty is a joy for ever. Its loveliness increases; it will never pass into nothingness.’”

“Hang on, Jeeves. I recognize that.”

“I am pleased to hear it, sir. It was the poet — “

“Don’t tell me. It was…the poet Keats, wasn’t it?”

“It was indeed, sir. The lines supply the opening of an early work, ‘Endymion.’”

We drove in silence for a mile or so. “I say, Jeeves, do you know, I think that’s the first time I’ve ever recognized one of your quotations.”

“I know, sir. I found it most gratifying.”

“You mean that after all these years something must be rubbing off?”

“I was always given to the belief that one’s education did not finish with the closing of the school gate, sir.”

“So this moment represents a…What’s that thing on a mountain top where one drop of rain goes to the Pacific and one to the Mediterranean?”

“A watershed, sir.”

“That’s the chap. Here’s to watersheds, Jeeves. Next left, isn’t it?”

(pp. 195-6)

It is as though Calvin could finally see life through Hobbes’ eyes. A final meeting of the minds. Oh, and yes, Jeeves gets married too! (Spoiler alert! But it is a comedy, and all classic comedies end with multiple marriages.)

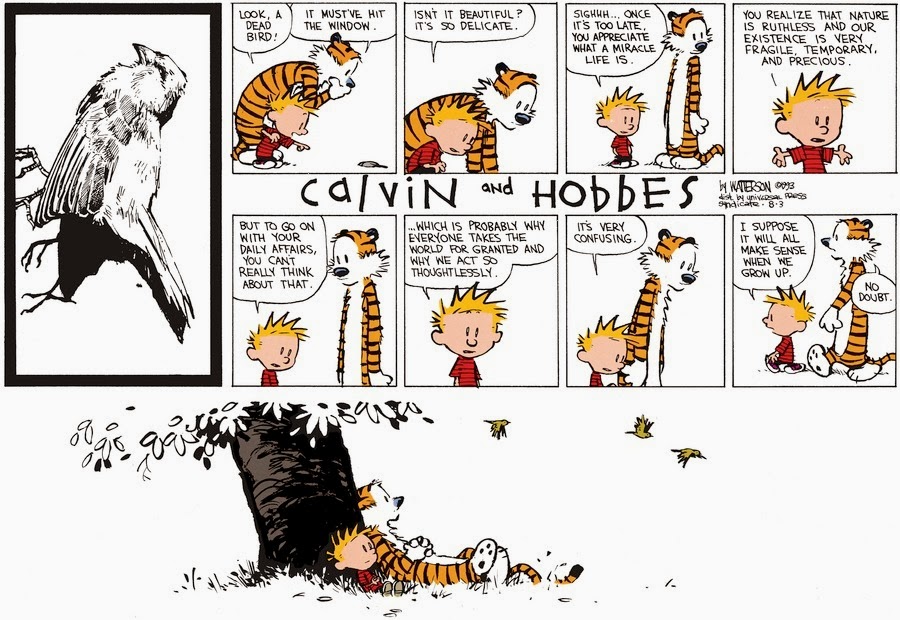

[A note here: it is not only humans that can help us achieve spirituality. Linked here is the story of a young woman (“Goldilocks and the Wolf: An Inspiring Tale of Wanderlust and Healing”) who was increasingly trapped in an abusive relationship. Her Siberian husky both helped her to realize the nature of the abuse (the boyfriend starting to abuse her puppy as well as her) and helped her get out into nature with its healing and meditative qualities, as well as helped her feel safe in forming new relationships.]But enough of the guys who are slow to mature if they do at all. They tend to remain in the fictional world defined by action and adventure with good or bad characters who don’t change (generally your 7 to 12 year old fare). In contrast, stories that involve character development and complex situations (not just complex plots), require more abstract skills of balancing justice and mercy, caring and fairness. So let us see what the girls can do! Starting with Jane Eyre (Bantam, 2003) , the iconic character created by Charlotte Brontë. [Brontë has been called the ‘first historian of the private consciousness’, Wikipedia] But just to show what could happen to Calvin if he kept an open mind in the company of Hobbes, let’s give another tribute to Bill Watterson with this classic meditation:

Jane Eyre

At age 10 Jane is living with her aunt whose son, John Reed, bullies her. When Jane finally tries to defend herself against her cousin, her aunt calls her a liar and locks her in the room in which her uncle died (her uncle adopted her after her parents died). When Jane is finally brought to account before her aunt, who gives her a morality book about lying, Jane tells her aunt:

At age 10 Jane is living with her aunt whose son, John Reed, bullies her. When Jane finally tries to defend herself against her cousin, her aunt calls her a liar and locks her in the room in which her uncle died (her uncle adopted her after her parents died). When Jane is finally brought to account before her aunt, who gives her a morality book about lying, Jane tells her aunt:

“I am not deceitful: if I were, I should say I loved you; but I declare I do not love you; I dislike you the worst of anyone in the world except John Reed: and this book about the Liar, you may give it to your girl, Georgiana, for it is she who tells lies, and not I.” (pg. 33)

Strong stuff for a girl who is almost alone in the world. Jane manages to be precocious at a young age and under oppressive circumstances because she has a good temperament, she manages to find people who help her behind the scenes (e.g. servants, peers), and she is determined to survive and ultimately thrive.

After this encounter it becomes obvious to both Jane and her aunt that Jane must leave the residence as soon as possible. Before she is sent to a boarding school, one of the household servants takes Jane into her confidence, revealing the she was looking after Jane behind the scenes in spite of the public scoldings she gave Jane in order to keep in good standing with her employer:

“And won’t you be sorry to leave poor Bessie?”

“What does Bessie care for me? She is always scolding me.”

“Because you’re such a queer, frightened, shy little thing. You should be bolder.”

“What! to get more knocks?”

“Nonsense! But you are rather put upon, that’s certain. My mother said, when she came to see me last week, that she would not like a little one of her own to be in your place.–Now, come in, and I’ve some good news for you.”

“I don’t think you have, Bessie.”

“Child! what do you mean? What sorrowful eyes you fix on me! Well, but Missis and the young ladies and Master John are going out to tea this afternoon, and you shall have tea with me. I’ll ask cook to bake you a little cake, and then you shall help me to look over your drawers; for I am soon to pack your trunk. Missis intends you to leave Gateshead in a day or two, and you shall choose what toys you like to take with you.”

“Bessie, you must promise not to scold me any more till I go.”

“Well, I will; but mind you are a very good girl, and don’t be afraid of me. Don’t start when I chance to speak rather sharply; it’s so provoking.”

“I don’t think I shall ever be afraid of you again, Bessie, because I have got used to you, and I shall soon have another set of people to dread.”

“If you dread them they’ll dislike you.”

“As you do, Bessie?”

“I don’t dislike you, Miss; I believe I am fonder of you than of all the others.”

“You don’t show it.”

“You little sharp thing! you’ve got quite a new way of talking. What makes you so venturesome and hardy?”

“Why, I shall soon be away from you, and besides”–I was going to say something about what had passed between me and Mrs. Reed, but on second thoughts I considered it better to remain silent on that head.

“And so you’re glad to leave me?”

“Not at all, Bessie; indeed, just now I’m rather sorry.”

“Just now! and rather! How coolly my little lady says it! I dare say now if I were to ask you for a kiss you wouldn’t give it me: you’d say you’d RATHER not.”

“I’ll kiss you and welcome: bend your head down.” Bessie stooped; we mutually embraced, and I followed her into the house quite comforted. That afternoon lapsed in peace and harmony; and in the evening Bessie told me some of her most enchaining stories, and sang me some of her sweetest songs. Even for me life had its gleams of sunshine. (pg. 37)

So Jane is sent to Lowood School where the headmaster indulges his own girls while he deprives his charges, malnourishing them and punishing them severely for the smallest infraction (Calvinism at its finest!). Adding insult to injury, Jane’s aunt tells the headmaster that Jane is a compulsive liar, and the headmaster brands Jane “Liar”, humiliating her in front of all her new schoolmates.

At Lowood Jane makes two particularly good friends with whom she has frank conversations, both theological and pragmatic. One girl, who dies of consumption, teaches Jane the discipline of serenity, replacing her tit-for-tat justice ideas with a turn-the-other-cheek perspective. The other, Helen Burns, teaches Jane the value of humility in the face of oppressive circumstances:

“You say you have faults, Helen: what are they? To me you seem very good.”

“Then learn from me, not to judge by appearances: I am, as Miss Scatcherd said, slatternly; I seldom put, and never keep, things, in order; I am careless; I forget rules; I read when I should learn my lessons; I have no method; and sometimes I say, like you, I cannot BEAR to be subjected to systematic arrangements. This is all very provoking to Miss Scatcherd, who is naturally neat, punctual, and particular.” (pg. 55)

In this way Helen takes to heart criticisms that have merit, no matter how hypocritical, self-righteous or cold-hearted the messenger. Although this is an example of a poor “fit” between Helen’s temperament and the rigidity of the school, Helen knows that when she is in no position to change things, she is better off lowering her expectations and self-esteem so as not to have one’s hopes and self-esteem obliterated.

Helen’s advice comes in good stead when Jane decides to confide in a sympathetic teacher about the abuse she experienced at home:

I resolved, in the depth of my heart, that I would be most moderate–most correct; and, having reflected a few minutes in order to arrange coherently what I had to say, I told her all the story of my sad childhood. Exhausted by emotion, my language was more subdued than it generally was when it developed that sad theme; and mindful of Helen’s warnings against the indulgence of resentment, I infused into the narrative far less of gall and wormwood than ordinary. Thus restrained and simplified, it sounded more credible: I felt as I went on that Miss Temple fully believed me. (pg. 72)

Jane was determined to get a good education so that she could get a good position as a governess, and her persistence paid off. The headmaster was eventually found out to be abusive and neglectful and was removed from his position:

Thus relieved of a grievous load, I from that hour set to work afresh, resolved to pioneer my way through every difficulty: I toiled hard, and my success was proportionate to my efforts; my memory, not naturally tenacious, improved with practice; exercise sharpened my wits; in a few weeks I was promoted to a higher class; in less than two months I was allowed to commence French and drawing. I learned the first two tenses of the verb ETRE, and sketched my first cottage (whose walls, by-the-bye, outrivalled in slope those of the leaning tower of Pisa), on the same day. That night, on going to bed, I forgot to prepare in imagination the Barmecide supper of hot roast potatoes, or white bread and new milk, with which I was wont to amuse my inward cravings: I feasted instead on the spectacle of ideal drawings, which I saw in the dark; all the work of my own hands: freely pencilled houses and trees, picturesque rocks and ruins, Cuyp-like groups of cattle, sweet paintings of butterflies hovering over unblown roses, of birds picking at ripe cherries, of wren’s nests enclosing pearl-like eggs, wreathed about with young ivy sprays. I examined, too, in thought, the possibility of my ever being able to translate currently a certain little French story which Madame Pierrot had that day shown me; nor was that problem solved to my satisfaction ere I fell sweetly asleep.

Well has Solomon said–“Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith.”

I would not now have exchanged Lowood with all its privations for Gateshead and its daily luxuries. (pg. 76)

Here is a description of another friendship Jane had at Lowood where she identifies the qualities and complementarities that made the friendship so valuable:

My favourite seat was a smooth and broad stone, rising white and dry from the very middle of the beck, and only to be got at by wading through the water; a feat I accomplished barefoot. The stone was just broad enough to accommodate, comfortably, another girl and me, at that time my chosen comrade–one Mary Ann Wilson; a shrewd, observant personage, whose society I took pleasure in, partly because she was witty and original, and partly because she had a manner which set me at my ease. Some years older than I, she knew more of the world, and could tell me many things I liked to hear: with her my curiosity found gratification: to my faults also she gave ample indulgence, never imposing curb or rein on anything I said. She had a turn for narrative, I for analysis; she liked to inform, I to question; so we got on swimmingly together, deriving much entertainment, if not much improvement, from our mutual intercourse. (pg. 79)

After leaving Lowood, Jane gets a governess position in the household of Mr. Rochester, the noble she eventually marries (after a very long and twisted plot!). Although Jane permits herself very few pleasures, she is quite intuitive, and describes her longing for a new life in the following:

The chamber looked such a bright little place to me as the sun shone in between the gay blue chintz window curtains, showing papered walls and a carpeted floor, so unlike the bare planks and stained plaster of Lowood, that my spirits rose at the view. Externals have a great effect on the young: I thought that a fairer era of life was beginning for me, one that was to have its flowers and pleasures, as well as its thorns and toils. My faculties, roused by the change of scene, the new field offered to hope, seemed all astir. I cannot precisely define what they expected, but it was something pleasant: not perhaps that day or that month, but at an indefinite future period. (pg. 102)

Early in their relationship, Rochester demonstrates a rough sympathy for Jane, a sympathy that Jane cannot help but notice, while disbelieving that he could possibly be enamored with her. In this encounter, Jane expresses her low self-esteem:

“Were you happy when you painted these pictures?” asked Mr. Rochester presently.

“I was absorbed, sir: yes, and I was happy. To paint them, in short, was to enjoy one of the keenest pleasures I have ever known.”

“That is not saying much. Your pleasures, by your own account, have been few; but I daresay you did exist in a kind of artist’s dreamland while you blent and arranged these strange tints. Did you sit at them long each day?”

“I had nothing else to do, because it was the vacation, and I sat at them from morning till noon, and from noon till night: the length of the midsummer days favoured my inclination to apply.”

“And you felt self-satisfied with the result of your ardent labours?”

“Far from it. I was tormented by the contrast between my idea and my handiwork: in each case I had imagined something which I was quite powerless to realize.” (pg. 133)

Later, when Rochester pays her a compliment, she uses her discipline to keep her emotions in check. We can see here how her education and talent work both for and against her, using her self-maligned artistic skills to put a firm fence to contain her self-esteem from expanding beyond the bounds of the socially acceptable:

When once more alone, I reviewed the information I had got; looked into my heart, examined its thoughts and feelings, and endeavoured to bring back with a strict hand such as had been straying through imagination’s boundless and trackless waste, into the safe fold of common sense.

Arraigned at my own bar, Memory having given her evidence of the hopes, wishes, sentiments I had been cherishing since last night–of the general state of mind in which I had indulged for nearly a fortnight past; Reason having come forward and told, in her own quiet way a plain, unvarnished tale, showing how I had rejected the real, and rabidly devoured the ideal;–I pronounced judgment to this effect:-

That a greater fool than Jane Eyre had never breathed the breath of life; that a more fantastic idiot had never surfeited herself on sweet lies, and swallowed poison as if it were nectar.

“YOU,” I said, “a favourite with Mr. Rochester? YOU gifted with the power of pleasing him? YOU of importance to him in any way? Go! your folly sickens me. And you have derived pleasure from occasional tokens of preference–equivocal tokens shown by a gentleman of family and a man of the world to a dependent and a novice. How dared you? Poor stupid dupe!–Could not even self-interest make you wiser? You repeated to yourself this morning the brief scene of last night?–Cover your face and be ashamed! He said something in praise of your eyes, did he? Blind puppy! Open their bleared lids and look on your own accursed senselessness! It does good to no woman to be flattered by her superior, who cannot possibly intend to marry her; and it is madness in all women to let a secret love kindle within them, which, if unreturned and unknown, must devour the life that feeds it; and, if discovered and responded to, must lead, ignis-fatus-like, into miry wilds whence there is no extrication.

“Listen, then, Jane Eyre, to your sentence: tomorrow, place the glass before you, and draw in chalk your own picture, faithfully, without softening one defect; omit no harsh line, smooth away no displeasing irregularity; write under it, ‘Portrait of a Governess, disconnected, poor, and plain.’

“Afterwards, take a piece of smooth ivory–you have one prepared in your drawing-box: take your palette, mix your freshest, finest, clearest tints; choose your most delicate camel-hair pencils; delineate carefully the loveliest face you can imagine; paint it in your softest shades and sweetest lines, according to the description given by Mrs. Fairfax of Blanche Ingram; remember the raven ringlets, the oriental eye;–What! you revert to Mr. Rochester as a model! Order! No snivel!–no sentiment!–no regret! I will endure only sense and resolution. Recall the august yet harmonious lineaments, the Grecian neck and bust; let the round and dazzling arm be visible, and the delicate hand; omit neither diamond ring nor gold bracelet; portray faithfully the attire, aerial lace and glistening satin, graceful scarf and golden rose; call it ‘Blanche, an accomplished lady of rank.’

“Whenever, in future, you should chance to fancy Mr. Rochester thinks well of you, take out these two pictures and compare them: say, ‘Mr. Rochester might probably win that noble lady’s love, if he chose to strive for it; is it likely he would waste a serious thought on this indigent and insignificant plebeian?’”

“I’ll do it,” I resolved: and having framed this determination, I grew calm, and fell asleep.

I kept my word. An hour or two sufficed to sketch my own portrait in crayons; and in less than a fortnight I had completed an ivory miniature of an imaginary Blanche Ingram. It looked a lovely face enough, and when compared with the real head in chalk, the contrast was as great as self-control could desire. I derived benefit from the task: it had kept my head and hands employed, and had given force and fixedness to the new impressions I wished to stamp indelibly on my heart.

Ere long, I had reason to congratulate myself on the course of wholesome discipline to which I had thus forced my feelings to submit. Thanks to it, I was able to meet subsequent occurrences with a decent calm, which, had they found me unprepared, I should probably have been unequal to maintain, even externally. (pp. 169-71)

Rochester is in fact enamored with Jane, but there are many circumstances (including dark secrets!) that make it impossible for them to act on their feelings (first and foremost, nobility do not marry servants!). None-the-less, Rochester is miffed at Jane’s refusal to flirt in the romantic way, so he endeavors to make Jane jealous by flirting with a famous beauty, Miss Ingram. Everyone assumes that Rochester and Miss Ingram are to marry, but Jane’s keen insight into character spares her feeling jealous of Miss Ingram because Miss Ingram, although beautiful and vivacious, lacks charm or the ability to charm Rochester:

There was nothing to cool or banish love in these circumstances, though much to create despair. Much too, you will think, reader, to engender jealousy: if a woman, in my position, could presume to be jealous of a woman in Miss Ingram’s. But I was not jealous: or very rarely;–the nature of the pain I suffered could not be explained by that word. Miss Ingram was a mark beneath jealousy: she was too inferior to excite the feeling. Pardon the seeming paradox; I mean what I say. She was very showy, but she was not genuine: she had a fine person, many brilliant attainments; but her mind was poor, her heart barren by nature: nothing bloomed spontaneously on that soil; no unforced natural fruit delighted by its freshness. She was not good; she was not original: she used to repeat sounding phrases from books: she never offered, nor had, an opinion of her own. She advocated a high tone of sentiment; but she did not know the sensations of sympathy and pity; tenderness and truth were not in her. Too often she betrayed this, by the undue vent she gave to a spiteful antipathy she had conceived against little Adele: pushing her away with some contumelious epithet if she happened to approach her; sometimes ordering her from the room, and always treating her with coldness and acrimony. Other eyes besides mine watched these manifestations of character–watched them closely, keenly, shrewdly. Yes; the future bridegroom, Mr. Rochester himself, exercised over his intended a ceaseless surveillance; and it was from this sagacity–this guardedness of his–this perfect, clear consciousness of his fair one’s defects– this obvious absence of passion in his sentiments towards her, that my ever-torturing pain arose.

I saw he was going to marry her, for family, perhaps political reasons, because her rank and connections suited him; I felt he had not given her his love, and that her qualifications were ill adapted to win from him that treasure. This was the point–this was where the nerve was touched and teased–this was where the fever was sustained and fed: SHE COULD NOT CHARM HIM.

If she had managed the victory at once, and he had yielded and sincerely laid his heart at her feet, I should have covered my face, turned to the wall, and (figuratively) have died to them. If Miss Ingram had been a good and noble woman, endowed with force, fervour, kindness, sense, I should have had one vital struggle with two tigers–jealousy and despair: then, my heart torn out and devoured, I should have admired her–acknowledged her excellence, and been quiet for the rest of my days: and the more absolute her superiority, the deeper would have been my admiration–the more truly tranquil my quiescence. But as matters really stood, to watch Miss Ingram’s efforts at fascinating Mr. Rochester, to witness their repeated failure–herself unconscious that they did fail; vainly fancying that each shaft launched hit the mark, and infatuatedly pluming herself on success, when her pride and self-complacency repelled further and further what she wished to allure–to witness THIS, was to be at once under ceaseless excitation and ruthless restraint.

Because, when she failed, I saw how she might have succeeded. Arrows that continually glanced off from Mr. Rochester’s breast and fell harmless at his feet, might, I knew, if shot by a surer hand, have quivered keen in his proud heart–have called love into his stern eye, and softness into his sardonic face; or, better still, without weapons a silent conquest might have been won.

“Why can she not influence him more, when she is privileged to draw so near to him?” I asked myself. “Surely she cannot truly like him, or not like him with true affection! If she did, she need not coin her smiles so lavishly, flash her glances so unremittingly, manufacture airs so elaborate, graces so multitudinous. It seems to me that she might, by merely sitting quietly at his side, saying little and looking less, get nigher his heart. I have seen in his face a far different expression from that which hardens it now while she is so vivaciously accosting him; but then it came of itself: it was not elicited by meretricious arts and calculated manoeuvres; and one had but to accept it–to answer what he asked without pretension, to address him when needful without grimace–and it increased and grew kinder and more genial, and warmed one like a fostering sunbeam. How will she manage to please him when they are married? I do not think she will manage it; and yet it might be managed; and his wife might, I verily believe, be the very happiest woman the sun shines on.” (pp. 197-9)

Later, Rochester tips his hand with the following well-crafted (for Jane, at least) compliment:

“I like to serve you, sir, and to obey you in all that is right.”

“Precisely: I see you do. I see genuine contentment in your gait and mien, your eye and face, when you are helping me and pleasing me–working for me, and with me, in, as you characteristically say, ‘ALL THAT IS RIGHT:’ for if I bid you do what you thought wrong, there would be no light-footed running, no neat-handed alacrity, no lively glance and animated complexion. My friend would then turn to me, quiet and pale, and would say, ‘No, sir; that is impossible: I cannot do it, because it is wrong;’ and would become immutable as a fixed star. Well, you too have power over me, and may injure me: yet I dare not show you where I am vulnerable, lest, faithful and friendly as you are, you should transfix me at once.” (pg. 232)

Let us briefly review Jane’s development up to this point. Her falling out with her aunt marked her entry into Character Formation, and her studies and friendships at Lowood broadened her perspective into Character Comparison. Now that her imagination has been stirred to consider the possibilities of a happy adulthood, she is longing to realize the hope that goes with the experience of the over-all joy of life. When she is longing for joy she is ready for hope. This puts her in the stage of Character Relation, with the following passage a good example of balancing feeling and judgment:

True, generous feeling is made small account of by some, but here were two natures rendered, the one intolerably acrid, the other despicably savourless for the want of it. Feeling without judgment is a washy draught indeed; but judgment untempered by feeling is too bitter and husky a morsel for human deglutition. (pp. 253-4; “deglutition” = “ability to swallow” [hee-hee!])

Jane knows well both her station and her mind, and when she finally expresses her feelings to Rochester and he proposes marriage, she states her modest hopes in the following way:

“I only want an easy mind, sir; not crushed by crowded obligations. Do you remember what you said of Celine Varens?–of the diamonds, the cashmeres you gave her? I will not be your English Celine Varens. I shall continue to act as Adele’s governess; by that I shall earn my board and lodging, and thirty pounds a year besides. I’ll furnish my own wardrobe out of that money, and you shall give me nothing but—”

“Well, but what?”

“Your regard; and if I give you mine in return, that debt will be quit.” (pg. 290)

OK, now for the Gothic part. Rochester’s facade crumbles when a fire exposes his secret. Rochester was married to a rich woman he was set up with when he was abroad in the West Indies. Her family knew she was insane but they were able to hide the fact. As a result of her destructive behavior, Rochester set up a private asylum in the attic of his mansion, with a servant paid handsomely to watch over her. When the servant got drunk, the wife would escape and try to murder Rochester. Jane does not know about this circumstance, but hears strange noises and rumors from the attic. Rochester’s wife finally sets the attic on fire and commits suicide. Trying to save his wife, Rochester becomes badly burned on one side of his body and loses his sight.

But not so fast. There is still a long story here that set the framework for Jane’s moral and spiritual development. Before Rochester’s secret was revealed, they finally resolved to get married. But through a family connection, the brother of Rochester’s wife hears of the marriage plan and intervenes to stop the marriage. In the wake of this, Jane escapes in the middle of the night to seek her fortune elsewhere.

Through a series of unfortunate events (sort of like Lemony Snicket) Jane loses her personal items and ends up nearly dying in the snow at a doorstep. She is rescued by St. John River who, with his sisters, nurse Jane back to health. Jane becomes fast friends with the sisters, and St. John eventually proposes marriage to Jane so that they can do missionary work in India.

While with this family, Jane learns that there is a family connection (St. John Eyre Knight) and that they have learned that Jane has come into an inheritance from her uncle (her aunt withheld this information from Jane). So Jane is in a position to set her own terms.

Jane knows that St. John is passionately in love with a great beauty, but denies himself permission to court her because she would not be suitable for missionary life, as Jane would be. St. John presses his proposal not only with great persistence, but as a moral imperative for them both. Jane’s insight into character keeps her from wavering in her refusal to accept his proposal — he does not have that mental serenity that she so craves for herself:

But besides his frequent absences, there was another barrier to friendship with him: he seemed of a reserved, an abstracted, and even of a brooding nature. Zealous in his ministerial labours, blameless in his life and habits, he yet did not appear to enjoy that mental serenity, that inward content, which should bet he reward of every sincere Christian and practical philanthropist. Often, of an evening, when he sat at the window, his desk and papers before him, he would cease reading or writing, rest his chin on his hand, and deliver himself up to I know not what course of thought; but that it was perturbed and exciting might be seen in the frequent flash and changeful dilation of his eye.

I think, moreover, that Nature was not to him that treasury of delight it was to his sisters. He expressed once, and but once in my hearing, a strong sense of the rugged charm of the hills, and an inborn affection for the dark roof and hoary walls he called his home; but there was more of gloom than pleasure in the tone and words in which the sentiment was manifested; and never did he seem to roam the moors for the sake of their soothing silence–never seek out or dwell upon the thousand peaceful delights they could yield.

Incommunicative as he was, some time elapsed before I had an opportunity of gauging his mind. I first got an idea of its calibre when I heard him preach in his own church at Morton. I wish I could describe that sermon: but it is past my power. I cannot even render faithfully the effect it produced on me.

It began calm–and indeed, as far as delivery and pitch of voice went, it was calm to the end: an earnestly felt, yet strictly restrained zeal breathed soon in the distinct accents, and prompted the nervous language. This grew to force–compressed, condensed, controlled. The heart was thrilled, the mind astonished, by the power of the preacher: neither were softened. Throughout there was a strange bitterness; an absence of consolatory gentleness; stern allusions to Calvinistic doctrines–election, predestination, reprobation–were frequent; and each reference to these points sounded like a sentence pronounced for doom. When he had done, instead of feeling better, calmer, more enlightened by his discourse, I experienced an inexpressible sadness; for it seemed to me–I know not whether equally so to others–that the eloquence to which I had been listening had sprung from a depth where lay turbid dregs of disappointment–where moved troubling impulses of insatiate yearnings and disquieting aspirations. I was sure St. John Rivers– pure-lived, conscientious, zealous as he was–had not yet found that peace of God which passeth all understanding: he had no more found it, I thought, than had I with my concealed and racking regrets for my broken idol and lost elysium–regrets to which I have latterly avoided referring, but which possessed me and tyrannised over me ruthlessly. (pp. 380-1)

In the next sentence, Jane sums up how St. John’s Calvinism cripples him emotionally:

“With all his firmness and self-control,” thought I, “he tasks himself too far: locks every feeling and pang within–expresses, confesses, imparts nothing. I am sure it would benefit him to talk a little about this sweet Rosamond, whom he thinks he ought not to marry: I will make him talk.” (pg. 402)

She does have a way to make him talk, but unfortunately, it does not improve him:

Again the surprised expression crossed his face. He had not imagined that a woman would dare to speak so to a man. For me, I felt at home in this sort of discourse. I could never rest in communication with strong, discreet, and refined minds, whether male or female, till I had passed the outworks of conventional reserve, and crossed the threshold of confidence, and won a place by their heart’s very hearthstone. (pg. 406)

St. John ends up in a dilemma: his time for departure to India had arrived, but Jane still had not consented to marry him. St. John’s either/or moralism comes to the fore full force as he attempts moral blackmail to get Jane to consent:

“Do not let us forget that this is a solemn matter,” he said ere long; “one of which we may neither think nor talk lightly without sin. I trust, Jane, you are in earnest when you say you will serve your heart to God: it is all I want. Once wrench your heart from man, and fix it on your Maker, the advancement of that Maker’s spiritual kingdom on earth will be your chief delight and endeavour; you will be ready to do at once whatever furthers that end. You will see what impetus would be given to your efforts and mine by our physical and mental union in marriage: the only union that gives a character of permanent conformity to the destinies and designs of human beings; and, passing over all minor caprices–all trivial difficulties and delicacies of feeling–all scruple about the degree, kind, strength or tenderness of mere personal inclination– you will hasten to enter into that union at once.” (pg. 442)

His aggressive persistence finally gets Jane’s righteous indignation in gear, and she gives him a sharp set-down:

“I scorn your idea of love,” I could not help saying, as I rose up and stood before him, leaning my back against the rock. “I scorn the counterfeit sentiment you offer: yes, St. John, and I scorn you when you offer it.”

He looked at me fixedly, compressing his well-cut lips while he did so. Whether he was incensed or surprised, or what, it was not easy to tell: he could command his countenance thoroughly.

“I scarcely expected to hear that expression from you,” he said: “I think I have done and uttered nothing to deserve scorn.”

I was touched by his gentle tone, and overawed by his high, calm mien.

“Forgive me the words, St. John; but it is your own fault that I have been roused to speak so unguardedly. You have introduced a topic on which our natures are at variance–a topic we should never discuss: the very name of love is an apple of discord between us. If the reality were required, what should we do? How should we feel? My dear cousin, abandon your scheme of marriage–forget it.”

“No,” said he; “it is a long-cherished scheme, and the only one which can secure my great end: but I shall urge you no further at present. To-morrow, I leave home for Cambridge: I have many friends there to whom I should wish to say farewell. I shall be absent a fortnight–take that space of time to consider my offer: and do not forget that if you reject it, it is not me you deny, but God. Through my means, He opens to you a noble career; as my wife only can you enter upon it. Refuse to be my wife, and you limit yourself for ever to a track of selfish ease and barren obscurity. Tremble lest in that case you should be numbered with those who have denied the faith, and are worse than infidels!” (pg. 444)

Some men don’t know when to fold a loosing hand, and keep putting higher stakes on the table — “Eternal fires of hell for you, woman!”

St. John leaves with instructions for Jane to join him at his point of departure. After his departure, she gets ready to leave and return to Rochester:

It wanted yet two hours of breakfast-time. I filled the interval in walking softly about my room, and pondering the visitation which had given my plans their present bent. I recalled that inward sensation I had experienced: for I could recall it, with all its unspeakable strangeness. I recalled the voice I had heard; again I questioned whence it came, as vainly as before: it seemed in ME–not in the external world. I asked was it a mere nervous impression–a delusion? I could not conceive or believe: it was more like an inspiration. The wondrous shock of feeling had come like the earthquake which shook the foundations of Paul and Silas’s prison; it had opened the doors of the soul’s cell and loosed its bands–it had wakened it out of its sleep, whence it sprang trembling, listening, aghast; then vibrated thrice a cry on my startled ear, and in my quaking heart and through my spirit, which neither feared nor shook, but exulted as if in joy over the success of one effort it had been privileged to make, independent of the cumbrous body. (pg. 458)

She finally finds her release from “the prison of adulthood”, gains her peace of mind, her hope and inspiration and joy in being able to return to Rochester. She finds his mansion burned to the ground, his body disabled by the fire, and himself personally needing a helpmate. He is now free to marry Jane. We can see Jane’s dry sense of humor when she responds to Rochester’s concern that his disfigurement is repulsive to her:

“Am I hideous, Jane?”, he asks. “Very, sir: you always were, you know”, she replies. (pg. 477)

Rochester’s misfortunes help Jane to become fully his equal as she can help him restore his physical and financial health. By the time they have a baby son, Rochester has regained enough of his sight to see their infant (and its bright-eyed smile!).

So this is the long, torturous path of Jane Eyre achieving spiritual development. Ta da!

And now for even more fun:

The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place

By Maryrose Wood (HarperCollins)

OK, this is a twisted spin on Jane Eyre where Penelope Lumley graduates from a boarding school (Swanburne Academy) and becomes governess to three feral children who were raised by wolves. (They became named Alexander Incorrigible, Beowulf Incorrigible and Cassiopeia Incorrigible.) Penelope has to figure out how to socialize and civilize them in spite of their enthusiastic impulsivity. Also, as in Jane Eyre, there are mysterious noises that come from the attic (the full moon howling of her employer Sir Frederick Ashton). Similarly, there are mysteries surrounding Penelope’s own identity even more mysterious than Jane Eyre’s.

It is a very complicated epic, and the last volume came out by June, 2018. What I want to focus on is Penelope’s coming of age and budding romantic interest in her friend and co-conspirator Simon Harley-Dickerson. Since the real story of their relationship starts in volume 5, the first 4 volumes are given in overview. For the overview, there is no better source than the author herself. The following synopses are taken straight from Wood’s website. I hope she likes it!

Now, for people who have read the books, the four volume overview can serve as a general reminder of the context of Penelope and Simon meeting. Since the epic is generally set in comic mode, and the protagonist is a Swanburne girl, we know it has a happy ending. The charm and splendor and profundity of the epic comes in the twists and turns of plot, the character development, the inner dialogue of Penelope, and the ways she overcomes adversity. But for those who have not read the series, you might want to use the four volume overview to whet your appetite to read the series, and then finish this section. Details from the last two volumes about Penelope and Simon may serve as spoilers for some, but the whole thing is such a cliff-hanger that we know the only way they can get through it is with their relationship. So take it either way: read first and then see what I have to say, or stay on the cliff with myself and Penelope and Simon, glimpsing some of their intimate interactions, without any of the plot interfering.

Book 1: The Mysterious Howling

Of especially naughty children it is sometimes said:

Of especially naughty children it is sometimes said:

“They must have been raised by wolves.”

The Incorrigible children actually were.

Found running wild in the forest of Ashton Place, the Incorrigibles are no ordinary children. Luckily, Miss Penelope Lumley is no ordinary governess. But mysteries abound at Ashton Place: Who are these wild creatures, and how did they come to live in the forests of the estate? Why does Old Timothy, the coachman, lurk around every corner? Will Penelope be able to teach the Incorrigibles table manners in time for the holiday ball? And what on earth is a schottische?

Book 2: The Hidden Gallery

The Incorrigibles are off to London for mystery, mayhem, and delicious desserts!

Thanks to the efforts of their plucky governess, Miss Penelope Lumley, Alexander, Beowulf, and Cassiopeia are less like wild animals and more like almost-proper children now. They are accustomed to wearing clothes. They hardly ever howl at the moon. And for the most part, they resist the urge to chase squirrels up trees. But a trip to London provides a slew of new challenges, and as clues to the children’s—and Penelope’s—past come to light, they find themselves swept up in an unexpected mystery.

Book 3: The Unseen Guest

More puzzling questions—rhetorical and otherwise—emerge in the Ashton woods. The hunt is on!

Miss Penelope Lumley and her young charges enter the Ashton woods where they uncover even more mysteries: How did the Incorrigibles survive their early years out of doors? Why are there sandwiches in the woods? And what on earth is an ostrich doing there? New guests arrive at Ashton Place, old friends visit from London, and a ghostly séance (not quite the social affair Lady Constance was hoping for!) takes place. But just who is the unseen guest?

Book 4: The Interrupted Tale

Penelope and the Incorrigibles head back to school —only to have their tale interrupted!

Optoomuchstic as ever, Miss Penelope Lumley returns to the Swanburne Academy for Poor Bright Females to speak at the annual Celebrate Alumnae Knowledge Exposition (or CAKE), but she finds her beloved school plunged into a six-letter word for chaos! With iambic pentameter, an A in “Great Orations of Antiquity,” and a pirate friend on her side, Penelope relies on her wolfish charges and her trusty Swanburne pluck to save her alma mater—and her job as governess.

Book 5: The Unmapped Sea

The Incorrigibles and Penelope take to the beach in hopes of breaking the Ashton curse!

Fredrick Ashton may not feel ready to be a father, but with a little Ashton on the way, he’s sure about one thing: The wolfish curse on his family must end before the child is born. When Lady Constance’s doctor prescribes a seaside holiday, Penelope jumps at the chance to take the three Incorrigible children to Brighton, where she hopes to persuade the old sailor Pudge to reveal what he knows about the Ashton curse. But the Ashtons are not the only ones at the beach in January…

At the beginning of the series, Penelope is an innocent girl who turns for comfort to her favorite book series about a pony named “Giddy-Yap Rainbow.” Giddy-yap is every girl’s pony dream, and the stories can keep coming and she will gobble them up.

By by the most recent book, Penelope has been hammered into a poised, resourceful and plucky governess who can juggle everything (almost) with swift and graceful pluck.

As the mysteries and risks mount, and the threat of doom looms, Penelope turns to her friend Simon for help. Simon is adept at getting in and out of scrapes himself, and between the two of them they keep the ball rolling amidst the insanity of the various family members and critters (squirrels and ostriches, oh my!). Finally they find out that to evade doom (Lord Ashton’s son being born while he is under a curse) they need to get the curse lifted by an ancient relative.

Roll it!

The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place: The Unmapped Sea

The romantic awakening of Penelope Lumley, putting a sensible even-tempered Swanburne girl on an emotional roller coaster.

Before we get Penelope started with Simon, I just love this passage about encouraging children’s fascination with museums as a way of helping them expanding their horizons and find their place in the cosmos:

This is the whole purpose of museums, of course. One does not go to merely collect facts and souvenirs and picture postcards, but to enlarge one’s notion of all that has been, and all that is, and all that might be. In this way we begin to understand what part each of us was born to play in the marvelous tale of existence. Put another way: We enter museums to look at the exhibits, but when we come out, it is ourselves we see more clearly. (Remember this the next time some well-intended adult suggests you spend a rainy afternoon reorganizing your sock drawer. “No!” you must loudly protest. “I wish to go to the mew-eezum, and enlarge my sense of life’s possibilities.” Remarkable adventures have blossomed from just such a request!)

So let’s rummage through some passages to reveal some of the furniture in Penelope’s heart.

Somehow (I said it’s complicated) Penelope comes across a display of a mollusk called the Seashell of Love. Its power is to reveal to the person attending to it their most secret love in the cave of their heart. When Penelope comes across it, she thinks of Simon, and her immediate reaction was:

Was it possible, after all? Was the Seashell of Love no ordinary mollusk?

Could she be in love with Simon? (pp. 199-200)

Well, yes, she could. But she doesn’t yet know her own mind on the subject. She remains in confusion, as expressed in this passage revealing her ambivalence:

Her sentiments began hopping willy-nilly from one emotion to its opposite. Simon’s arrival was the best — and worst — and best — thing that could have happened! She wanted to see him and hide from him, and tell him and not tell him what was in her heart. But she was a Swanburne girl, after all, and her pluck and common sense had been largely restored by a good night’s sleep. (pg. 228)

We can watch Penelope use eye avoidance to modulate her feeling in this passage:

Only after Penelope had taken a few calming sips did she dare sneak a look at her friend. Had he changed, since last they met? Or was all the change in her? “I am glad to see him,” she decided, but I must no let myself be too glad, or I shall not be able to maintain my composure,” and so she found herself glancing away from him every thirty seconds or so, by redirecting her gaze at the carpet, or the wallpaper, or the ceiling. (pp. 239-240)

OK, this is getting a little uncomfortable, so let’s change the subject for a bit. Penelope and Simon have a critical duty to get the curse lifted from Lord Ashton before his son is born, and the only way they have found to do it is to trick Old Pudge into revealing what the curse is. But Pudge swore an oath that he would never reveal the oath to anyone. So here they present the Ethical Dilemma (take note Kohlberg!):

He paused. “But is it right to try to trick old Pudge into breaking his oath, even if it is for a worthy cause? It feels like an ethical dilemma to me.”

(Ethical dilemmas are like the sevens and eights of the multiplication tables, which is to say, they are a particularly tricky kind of problem. They occur when the difference between right and wrong is shrouded in mist. For example, is it ethical to steal a loaf if bread to save the life of a starving child? Is telling a friend that his appalling new haircut looks fantastic a dreadful lie, or simply good manners? Is it ever right to throw one person to the wolves so that others might escape harm? Such questions keep philosophers in business, and the rest of us scratching our heads.)

Penelope and Simon talked it over. They decided that Pudge’s loyalty to the admiral was praiseworthy, but the admiral’s true intention ought to be considered as well. “No doubt he swore Pudge to secrecy to protect his family, but surely his purpose would be better served by undoing the curse itself. We must think of the Baby Barking Ashton,” Penelope observed, and Simon agreed. (pp. 232-233)

OK, it’s exciting and distracting, but so is love! As Penelope discovers:

In a flash her mind scampered in his direction, like a spaniel helplessly bounding after a squirrel. “Simon, and nothing but Simon!” she inwardly lamented, as a lovelorn sigh escaped her. “This business of being in love is terrible inconvenient. In the first place, it is distracting beyond reason, and in the second place — well, so far it is comically one-sided! How on earth is one person supposed to have any notion of how another person feels? Though I suppose that is what poetry is for.” (pp. 234-235)

That is what poetry is for. And music too! Anyway, in the midst of all this Penelope comes into possession of a set of letters Simon sent to her while he was captive of pirates. They were messages in bottles that somehow (complicated again!) got to Penelope without Simon knowing (but he was hoping they would, but the chances were next to nil that any of them would). All we have to do is read Penelope’s reaction to know what was in them (poetry, of course!):

Penelope put down the letters and sat quite still.

She was shocked. Shaken. Overjoyed! Dismayed! And above all, thoroughly confused.

“Perhaps he was just lonely at sea,” she thought, not daring to hope. Even so, he had felt that way about her, once. Might he still? (pp. 234-235)

But she’s a Swanburne girl, and brings herself to discipline as is her habit:

She bid Simon farewell and watched him go, with the tiniest ache in her heart that she quickly and firmly put out of her mind. (pg. 274)

Nice try, Penelope! We know what is going to happen in barely a page:

The ache in her heart came back doubled. Did Simon Harley-Dickerson love her, or did he not? All day Penelope had been on the look-out for evidence as to which way the wind blew, so to speak, but over-all he seemed the same cheerful, kind, clever and throughly loyal Simon she had known for more than a year.

“Compared to the horrible throes of lovesickness suffered by Master Gogolev, Simon shows no signs at all of romantic torment,” she thought. “I suppose that answers my question, and I ought not to think of it anymore. Blast the Seashell of Love! I have been caught in a whirlpool because of it, but I expect in time I will find calm waters once more.” (pg. 275)

Ah, the wily ways of self-deception. Let’s let up on Penelope for a bit, and get back to those Ethical Dilemmas:

Such shameless eavesdropping would previously have posed an ethical dilemma for Miss Penelope Lumley, who, as a schoolgirl, had once stitched A Swanburne Girl Minds Her Business onto a pillow, but no more. The stakes were too high.

OK, I’m going to keep this one as simple as possible. Simon and Penelope devise an epic deception to trick a party of people into believing that they are at a formal dinner party on a ship and that the ship leaves port and arrives at a destination at the end of the party. Into this deception Simon inserts a discourse on Coleridge’s “willing suspension of disbelief”:

“Why, I could swear I hear the crash of the waves!” Mrs. Clark exclaimed. This was thanks to the use of what Simon called an ocean drum, which was simply a large quantity of dried beans swirled rhythmically inside a box. The Incorrigibles had made one according to Simon’s specifications and hidden themselves behind the rigging to contribute this sound effect as the guests arrived. This too was Simon’s suggestion. “If you hook the audience right away with something that has a bit of truth in it, their imaginations will do the rest,” he had explained. “They’ll follow you anywhere!” (Interestingly, the idea that the imagination of the audience can be relied upon to accept even highly unlikely plots was invented by the same Mr. Coleridge who wrote “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” He called it “the willing suspension of disbelief.” To this very day, most of us are more than willing to suspend our disbelief if it means we can enjoy a rollicking tale about gloomy supernatural birds, angry wolves that spew curses, seashells with romantic insights, or other, well…unusual topics.) (pg. 309)

OK, that was interesting, and gave Penelope a momentary break from her confused heart, but we should not leave her dangling for long. Because it is bound to happen — eye contact!

Without meaning to, Penelope found herself glancing at Simon, only to catch him looking at her at the same time. Embarrassed, she tore her gaze away — that unruly hair! that gleam of genius! and oh, that uniform! — and fixed it on her employers instead. No magical mollusk was needed to pry the truth from their hearts, for it was plain to see. Despite Lord Frederick’s uncontrollable woofing, and his wife’s immeasurable foolishness, l and the fact that everything around them was made of paint and papier-mâché, they looked, in a word, happy. Happy, and in love! This imaginary voyage had served its purpose so well that Penelope found herself wishing real, true contentment for this moon-crossed couple, land for the Barking Baby Ashton, too.

“But not at the expense of anyone else,” she thought stubbornly. “I know what the curse said, but no one ought to be thrown to the wolves to assure the happiness of others. No true happiness can be purchased at such a terrible price.” (pp. 321-322)

When she starts mixing her romantic feelings with her ethical dilemmas, you know Penelope is about ready. But not just yet! Bless her soul, Maryrose Wood throws in a parody of Occams’ Razor:

(Here Lady Constance unwittingly echoed the famous William of Ockham, who lived in the fourteenth century and who died, alas, of the plague, but not before saying this: When there is more than one explanation at hand, the simplest one is best. His idea has come to be known as Occam’s Razor, a sharp blade that shaves away the stubble of needless complexity. Also, note that Occam is the Latin spelling of Ockham. If you think that having two spellings for the same name is precisely the type of needless complexity that could do with a nice, close shave, congratulations; you have clearly understood the meaning of Occam’s Razor.) (pp. 323-324)

OK, enough fooling around. Time for Penelope to melt:

At this moment Miss Penelope Lumley had what is known as an epiphany, which is a way of saying that she understood something extremely complicated all at once, as if a puzzle with many pieces had suddenly flown into the air and assembled itself. The force of it hit her broadside and she found herself leaning first port, then starboard, until she toppled into Simon’s arms.

“Whoa, there!” He put her back on her feet. “That’s quite a Sea Sway. Must be a storm brewing.”

“The split in the Ashton family was between Pax Ashton and his twin sister, Agatha,” she said in a rush. “And somehow, Agatha Ashton grew up to be Agatha Swanburne!”

Simon rubbed his chin. “So, on one side of the curse are Pax’s descendants — first Edward, then Frederick, and soon, the wee woofing baby of Ashton Place. But who are Agatha’s descendants?”

“Miss Charlotte Mortimer is one. She told me so herself; Agatha Swanburne was her grandmother.” Penelope felt suddenly groundless, as if she were falling headlong through the air, but at the same time it felt like flight, like joy. “I — I am not sure. I think there may be others. In fact…I think…that is to say, I have come to suspect —“ (pp. 334-335)

Interesting that Penelope has both a romantic epiphany (swooning into Simon’s arms) and an intellectual epiphany (realizing not just a branch, but the trunk of her family tree). She doesn’t yet have all the details, but she is now on the spiritual path. Good go, Penelope!

Oh, but if you haven’t been reading these books yourself, you should know that they are cliffhangers (Lemony Snicket style, quite the compliment). In that light, it is no surprise that the penultimate volume ends like this:

But never in her life could Penelope recall feeling more hopeless than she did now. Not even the words of Agatha Swanburne offered any comfort; she felt she could not remember a single saying if her life depended on it. (pg. 402)

[I wrote this before the final volume was published: “So, dear readers, if we wait for the final volume this fall, there may be more on this story. But as it is, we can only wish Penelope and Simon well!”]The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place: The Long Lost Home

The final volume takes on historical-allegorical elements as Penelope is swept off (essentially sold off and kidnapped) to Russia, learns more Shakespeare and Tolstoy than she had planned, and is stuck in a depressed village as the governess of the Babushkinov children. In contrast to the Incorrigibles, who are poor and resourceful and ready to learn, the Babushkinovs are rich and spoiled and immune to new information. One cannot but notice the similarities with the resourceful Obama and spoiled Trump families (like the Trumps, the Babushkinovs live beyond their means, often don’t pay debts and use dicey means to get money). But that is not the focus of this article. The focus will be on Penelope’s growing sense of gratitude as part of her budding spirituality and romantic life.

The final volume takes on historical-allegorical elements as Penelope is swept off (essentially sold off and kidnapped) to Russia, learns more Shakespeare and Tolstoy than she had planned, and is stuck in a depressed village as the governess of the Babushkinov children. In contrast to the Incorrigibles, who are poor and resourceful and ready to learn, the Babushkinovs are rich and spoiled and immune to new information. One cannot but notice the similarities with the resourceful Obama and spoiled Trump families (like the Trumps, the Babushkinovs live beyond their means, often don’t pay debts and use dicey means to get money). But that is not the focus of this article. The focus will be on Penelope’s growing sense of gratitude as part of her budding spirituality and romantic life.

Penelope manages a series of escape tactics that starts with her getting herself from the depressed town of Plinsk to St. Petersburg. At her first glimpse of freedom, she has the following experience of gratitude while gazing at St. Peter’s Ship atop the golden spire:

All those unhappy days and nights in Plinkst might have dimmed her Swanburnian spirit, temporarily. But this new feeling within, this swelling gratitude and simple delight — it was something more than optimism. It was more, even, than optoomuchism. She suspected that Tolstoy fellow would understand straight away. It was the true, clear knowledge that no matter what might happen later, for this single hour her eyes were wide open to the splendor of it all, the golden spire against a crisp blue sky, and the mirrored surface of the winding Neva reflecting them both, and even more perfect version of this already glorious world. (pp. 165-6)

OK, away from the plot, let’s get to it. We know the meetings between Penelope and Simon have been improbable to the extreme, but somehow they have always happened in the past. So just as it seems impossible that Simon and Penelope should ever see each other again, so it is fated. In short, here is what happened when they first can relax and face each other:

Simon held her gaze.

“And what of you? And me?”

Penelope blushed but did not look away. (pg. 432)

Interesting how romantic gaze and mother-infant gaze have similarly over-stimulating qualities that take management. Here she let’s him make eye-contact, while not looking away she ends up blushing (confusion = fusion of mind and body = blushing). Next:

She looked down at her hands, now folded neatly in her lap. His rested carelessly on his knees. The question of what it would be like to hold hands took shape in her mind at the exact moment his hand reached out and took hers.

“I believe — yes, I do understand.” Then she smiled, and so did he, and all nervousness left her, for it seemed a decision of sorts had been made between them. But all she said was “Do you think Bertha will mind waiting just a bit longer to go home?” (pp. 436-7)

For any more, you have to read the books yourself. Do yourself and your loved ones a favor and do it soon! Now that we know there is safe harbor for Penelope and Simon, I will end this section with this aside Maryrose Wood (related to another special part of the plot that Simon succeeds in pulling off while in disguise, but again, read it yourself!):

(Which only goes to prove — although no further proof is needed — that sometimes “just the right words” are no words at all. No disrespect to Shakespeare, Tolstoy, or Moby Dick is intended by this, for every poet knows it already. As the proverb tells us, “Speech is silver, silence is golden.” And nothing more need be said about that!”) pg. 356

The End: Personality and Story

Now that we have mixed research and literature, let’s extrapolate on both ends. This is a section at the end of my article on temperament and development (click here for link) which uses The Bagthorpe Saga (Helen Cresswell) to show how goodness of fit parenting contrasts with the badness of fit Bagthorpe parenting, and the How to Train Your Dragon saga (Cressida Cowell) to consider how this research fits into a larger narrative theory.

The Bagthorpe Saga was a comic saga: it never had a bad end, but it never had a good end either. In fact, it reportedly had no end (according to the author, at least), but history shows that Book 9 was the last she wrote. In the end of the saga as reported, the crash that ruined the Bagthorpe pride was also the salvation of Fozzie’s reputation. If not a happy ending, at least some poetic justice. But most stories aren’t sagas — even epics have endings.

Personally I like the way Cressida Cowell ends the tragic-comic epic How to Train Your Dragon (book 12, pp. 459-60). Through the most grueling of earthly gruel, Hiccup Horrendous Haddock III manages to save both the humans and the dragons, achieving victory on the Island of Tomorrow:

THE HERO CARES NOT FOR A WILD WINTER’S STORM,

FOR IT CARRIES HIM SWIFT ON THE BACK OF THE WAVE,

ALL MAY BE LOST AND OUR HEARTS MAY BE WORN,

BUT A HERO…FIGHTS…FOREVER!

And if that moment doesn’t last forever … then it really ought to.

So that is where we will leave them, Hiccup and his friends: forever young, forever hopeful, singing their hearts out on the Island of Tomorrow.

BECAUSE…

If it doesn’t end well then it isn’t

Heroine from a rival tribe: yes, a Romeo and Juliet story among the rude northerners who once flew with the dragons!

THE END

P.S.S. I will add on a list of my favorite literature. Aside from Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and all the great English children’s literature (Phantom Tollbooth, Charlotte’s Web, Wind in the Willows, etc.).

The Bagthorpe Saga (9 books) by Helen Cresswell. Fast paced and funny as hell, describes the adventures of the Bagthorpe family where sibling rivalry, birth order dynamics, and relentless one-upmanship are revealed in the best of English comic writing. I use this saga to illustrate many points in my Determinants of Behavior article here (the second half of the article is all things Bagthorpe).

How to Train a Dragon series by Cressida Cowell. Wild and fanciful fantasy about pre-historic Vikings who have a love-hate relationship with dragons. The books are better than the movies, and the movies are better than the Disney-on-ice production, but it’s all good. But the books are the best.

The Cottage Tales of Beatrice Potter series by Susan Wittig Albert, mixing the biography of Beatrice Potter with a fantasy of her characters come alive. Priceless. Children respond well to talking animals because the animals have awkward times doing human things with animal bodies — a feeling that children often share. The Paddington Bear books are a good example. An American series that is the equivalent to Beatrice Potter is:

The Freddy the Pig series by Walter R. Brooks. 26 in total, and out-sold Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys series. That’s a lot of books and a lot of piggy adventures. Freddy, like Paddington, relies on his friends to help solve the conflicts. In fact, it seems that most favorite children’s stories involve friends solving the problem rather than a single “hero”: this mirrors the plots devised by girls more than boys (see Sutton-Smith, 1972, The Folkgames of Children).

The Series of Unfortunate Events series and All the Wrong Questions series by Lemony Snicket.

Dostoevsky, particularly the Brothers Karamazov, and Faulkner, particularly the Snopes series (his funniest!).

Leo Rosten, Jewish humor, any of his stuff (including Yiddish and Yinglish dictionaries), but most especially his American classic, Oh Kaplan! My Kaplan!