However, the existence of an enigma is not a physics question. It’s metaphysics in the original sense of that word. (Metaphysics is the name of Aristotle’s work that followed his scientific text Physics. It treats more general philosophical issues.) When it comes to metaphysics, non-physicists with a general understand of the experimental facts — facts about which there is no dispute — can have an opinion with a validity matching that of physicists. (Quantum Enigma, pg. 102)

Let’s begin with this: physicists don’t know what gravity is, biologists don’t know what life is, psychologists don’t know what consciousness is, but mystics do know what bliss is. [Is that because mystics don’t need statistics?]

Let’s begin with this: physicists don’t know what gravity is, biologists don’t know what life is, psychologists don’t know what consciousness is, but mystics do know what bliss is. [Is that because mystics don’t need statistics?]

I will be using an open-system philosophy, along with some leading books by physicists and about quantum theory to systematically critique a materialist apologist, Sean Carrol, and his book The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself, Dutton (2016). [Later I will address Carrol’s more recent book, Something Deeply Hidden: Quantum Worlds and the Emergence of Spacetime (Dutton 2019)]. These books are:

The Fifth Dimension: An Exploration of the Spiritual Realm (2nd ed.) by John Hicks, Oxford (2004). Makes a clear and thorough case that naturalism fails to account for spirituality throughout human history, and that a spiritual dimension is necessary to understand the four dimensions of physics as well as the mystical experiences of well-regarded spiritual leaders. In this way, we can understand the basis of reality, information, as a non-physical reality that gives form to all matter.

Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness (2nd Ed.) by Bruce Rosenbaum and Fred Kuttner, Oxford (2011). This is a textbook developed by two physics professors at UC Santa Cruz for an undergraduate course for non-science majors. While at UCSC I took three quarters of Introductory Astronomy to fulfill my undergraduate natural science requirement. I have maintained an interest in astrophysics ever since.

Spooky Action at a Distance: The Phenomenon That Reimagines Space and Time — And What It Means for Black Holes, the Big Bang, and Theories of Everything by George Musser, Scientific American, (2015). Written by an award-winning science journalist, he tracks in detail the controversies and discoveries involved in physical non-locality.

The Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safe for Quantum Mechanics by Leonard Susskind, Little Brown & Co, (2008). Makes the case that black holes conserve rather than destroy information. Uses an array of analogies to help the layman understand the concepts.

Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Universe’s Hidden Dimensions by Lisa Randall, HarperCollins (2005). Probably the most delightful and fun to read science book I have come across. Where Susskind is brilliant, Randall is dazzling.

The reality of the weirdness of reality (e.g. that one thing can be in two places at once) is driven home by the fact that 1/3 of our economy is based on practical applications of these experimental discoveries. Electronics such as lasers, transistors, MRI scanners and other highly technical electronics use the fact of “super-position” (e.g. a proton being in two places at once through its wave action) to work their miracles (Quantum Enigma, pp. 115-123). Scientists have now created nano-transmitters and in October 2016, the Nobel Prize for chemistry was awarded to scientists who built a molecular size machine, the first real step toward developing “quantum computers” based on super-positions.]

It is interesting that each of these books expresses confidence in the layman’s ability to understand how weird reality is now found to be by science. Significant for this is the fact that many physics concepts come not from physical experiments or mathematical formulae, but from “thought experiments.” Einstein was particularly noted for this, but when reading these books, one becomes aware that physical experiments and mathematics more serve to refine and verify a theory resulting from a thought experiment than the other way around. This is still based in empirical evidence, because the thought experiments try to detect the sources of contradictions between existing theory and evidence. As a result, quantum terminology has become replete with metaphors and literary allusions. [Susskind refers to “mental pictures”, which are one version of metaphors and models.]

So let’s dive in. First, some terminology to consider and some side issues to discard:

“Brute Fact”: This is a phrase often used in philosophical discussions of scientific issues. It has two distinct but often conflated meanings. The first is an irreducible phenomenon, such as a foundational particle in physics (that cannot be broken into parts). As general concepts, matter and energy are also “brute facts.” But then life, consciousness, and bliss are also irreducible phenomena. The tricky part comes in with the “brute” part of the phrase, which is often used to invoke a competitive philosophy such as Hobbes’ view of life as “red with tooth and claw” (e.g. “evolution is a brute fact and kindness is nothing but weakness and hypocrisy”). Sorry fellas, “survival of the fittest” is about mating more than killing, and successful mating is usually a cooperative activity, at least if one wants a happy mother and a healthy baby.

“Of course, it is nothing but…”: This phraseology, which can be found in a number of “scientific” studies, is nothing but a dodge by someone who is not prepared to explore the philosophical ramifications of a finding. The “of course” part conveyed the impression that if you don’t agree it is because you don’t understand (“poor stupid you”). It is used by reductionists of various stripes: materialists, physicalists, naturalists (even “poetic” ones), and even some functionalists.

“Gestalt Whole/Part”: The fundamental gestalt maxim is that “the whole is other than the sum of its parts.” This is the template I will use to evaluate cosmologies. In the fields of cosmology and emergence, some of the more technical studies have developed terminologies that I find tedious and unnecessary, and I will avoid them like the plague. Instead, I will point out that the ideological extremes in both science and religion break the gestalt: 1) scientistic materialists claim that the whole not only is not different than its parts, but it is an illusion generated by the parts (the implicit goal is to become disillusioned); fundamentalist theologians claim that not only is the whole different than the parts, but that the parts are irrelevant and should be treated with disdain (the implicit goal is to punish what is natural).

“Infinity and the Anthropic Principle”: The Anthropic Principle enumerates all the necessary conditions for human life to evolve on earth, starting with the masses and charges of elementary particles, through the cosmological creation of carbon, the unique qualities of water, etc. etc. The chances of this happening randomly has been calculated to be so ginormous that it almost seems like infinite (10 to the 120th power, to be somewhat exact). Paul Davies, in his book Cosmic Jackpot: Why Our Universe is Just Right for Life (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), articulates the anthropic principle in exacting terms, showing how we exist in a unique reality that is incomprehensibly beyond random processes to create. But instead of being grateful of our vulnerable existence and its possibilities for joy and suffering, he decides that there is no ultimate reality and that our existence is a mere statistical anomaly due to the infinite possibilities that must exist just because “infinity.” This is what happens when you conflate the quality of infinity with the “quantity” of infinity. In this context, it is easy to call in infinity to explain our improbability. But when you try to quantify probability in comparison to infinity, probability gets dwarfed and next to eliminated. In the face of infinite quantity, quantum probability cannot exist. As Susskind puts it: “I suspect that infinity has been a prime cause of insanity among mathematicians.” (pg. 332) If infinity is mis-construed as a number rather than as a quality, fools are going to get lost in their own rabbit holes.

“Instruments of Measure and Instruments of Co-Creation”: An occupational hazard of science is to communicate in the passive voice. Instead of “I measured the speck on the screen,” more often what we read is “The speck on the screen was measured.” This is not a problem except for the fact that people start to believe that science exists without human participation. A simple example of this is that there is a preference to describe things in ways that reduce the appearance of human involvement — e.g. a preference to say that the mark of a particle is made on a sheet of slate rather than a photographic screen because a sheet of slate might just happen to be in the particle’s way whereas a photographic screen requires a human to set it up (see Quantum Enigma). An extreme example of this is the following:

“The Monkey Who Wrote Shakespeare”: A thought experiment often used to defend the idea that evolution is a random process resulting from infinity is the idea of the monkey who wrote Shakespeare. Sounds like a great proposal for a research grant! So how would this work?

We cannot go back to monkey natural history before Shakespeare and start distributing typewriters, so we will have to take a more practical approach. First of all, who is going to breed all those monkeys? What typewriter factory is going to manufacture all those typewriters? Who is going to get all those typewriters to the monkeys and reinforce them to bang away endlessly on the typewriters? Who is going to put in all the sheets of paper, take them out, and compare them to Shakespeare? And how does one judge if a monkey is truly successful — there are several “folios” of different versions, and what if there is a typo? Monkeys may know the difference between a typo and a banana, but they don’t know the difference between a typo and a non-typo. Perhaps we can get around this by giving the monkeys enough time to invent their own computers and program them to randomly produce text that can be text checked to Shakespeare (this is getting more credible as we go!) So this is a massively failed thought experiment because it assumes a massive amount of human intervention while hiding it all in passive language.

OK, Now that I have got that off my chest, let us work our way up the dimensional developmental double helix and see how we get from one dimension to five. This section will be structured by perspectives presented by Lisa Randall and the Overview Effect.

Dimensional Terms:

Zero Dimension (0D) = point

One Dimension (1D) = line

Two Dimensions (2D) = plane (flatland)

Three Dimensions (3D) = cube

Four Dimensions (4D) = space-time

Five Dimensions (5D) = quantum enigma (warped space-time)

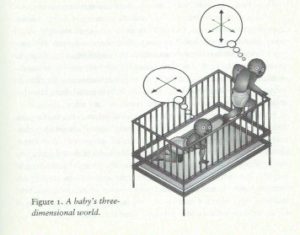

With this graphic, Lisa Randall begins her experiential exploration of dimensions. The baby in the crib first experiences the two-dimensions of the crib floor, and then rises to the third dimension by climbing up the crib rails.

I am going to take this up a two spiral staircases: individual and evolutionary. The individual spiral starts with the observation by Randall, the rest is my extrapolation.

1) As we found with the advent of language, an important part of this development is the toddler getting up on her two feet and established in the three-dimensional world.

2) With the internalization of language and the understanding of mental verbs, young children explore their interior three-dimensional world.

3) When children can keep their promises, perform “concrete operations” and understand “conservation and reversibility”, they become what philosophers and scientists (both social and physical) call “Naive Realists.” Jerome Bruner identifies naive realism as the assumption that there is an objective world out there that is the same for everybody. He rightly points out that most of us most of the time implicitly operate as naive realists because under ordinary circumstances it works “for all practical purposes.” Naive realists used to believe that the earth is flat and the center of the universe, but modern education has introduced our pre-teens to the globe, the sun, and the solar system as images to believe in as naive realists.

4) Abstract thinking allows for the understanding of classical Newtonian physics. This is a stretch for most people, even those gifted with math ability. But once Newtonian calculus becomes routine for the math proficient, Newtonian determinism becomes hard to shake off. From this perspective, the “quantum enigma” requires cognitive “re-wiring.”

[Many] physicists, when pressed to respond to the strangeness of the micro-world, might say something like: “That’s just the way Nature is. Reality is just not what we’d intuitively think it to be. Quantum mechanics forces us to abandon naive realism.” And they’d leave it at that. Everyone is willing to abandon naive realism. But few physicists are willing to abandon “scientific realism,” defined as “the thesis that the objects of scientific knowledge exist and act independently of the knowledge of them.” Quantum mechanics challenges scientific realism. (Quantum Enigma, pg. 139.)

5) Except for moderately large objects in the middle of the universe, most of reality does not abide by the “billiard ball” determinism of efficient causality. When you get to the smallest scales, the largest scales, the furthest reaches, the densest points, and the hottest and coldest conditions, everything gets too weird for anyone to explain. But ways of understanding these phenomenon are emerging.

Now for the evolutionary spiral. This is my elaboration on how the Overview Effect is explained:

- The fish in the ocean exist in a fluid medium with which they merge and emerge through currents and pools and time. They cannot see the ocean from above nor the land from below. Their experience is essentially two-dimensional.

- Amphibians come up on the land, can see what is immediately on the land, and can look back to see into the water before they return to the water. This ability gives them an experience of a dimension not open to the fish.

- Primates can go bi-pedal, go to vista points to see the horizon, climb trees and swing from tree to tree. Human primates can do some of this, but also can watch birds, imagine flying, and invent ways to fly. This makes it easier to project 3D space into the future, thus completing the fourth dimension (when you project into the future, you can also imagine the present as past).

- Flying humans can see the curvature of the horizon, but not the globe spinning separately in black space. The overview effect stimulates gratitude and the intuition of being in a mature curious adult.

Now that we have the Overview, let’s dive into the controversies presented by “poetic naturalism”.

Sean Carroll: Poetic Naturalism, the Big Picture, and the Death of Deism

Sean Carroll presents recent findings in physics to make the case that metaphysics is an unnecessary complication obstructing our ultimate understanding of reality which he believes can and will be achieved in wholly natural terms.

In order to account for life and consciousness, he relies on a theory of emergence that allows for the emergence of life and consciousness without any non-physical causes involved. This is because he considers emergence to be a way that different aspects of something come into being when exposed to a new situation. Each aspect is a different story about the thing which emerges naturally from the thing itself responding to the new situation — therefore he considers stories (not atoms or subatomic particles) to be the fundamental basis of nature (quoting poet Muriel Rukeyser: “The universe is made of stories, not atoms.” pg. 19). To sum it up, he calls his theory “poetic naturalism,” which apparently is some kind of nature of the poetic variety.

But poetry is not “natural”; it is “made” or “arranged.” In that sense, it is “artificial” — a product of the imagination. Remember this about theories: Einstein said that imagination is more important than knowledge. Carroll demonstrates a broad and detailed knowledge of physics, but his imagination fails us when he tries to get his mind around poetry. And metaphysics.

Indeed, Carroll’s idea of credible poetry seems to exclude its main characteristic: metaphor. For Carroll, each aspect of a thing is a scientifically verifiable state of that thing, like steam is an aspect of water when it is boiled. Now, I agree with this basic epistemology, but it is not poetry. Speculation is belittled by Carroll unless it is his speculation that physics will ultimately account for a unified theory of reality.

Victor Frankl once wrote: “The problem is not that scientists are specializing, but that specialists are generalizing.” When Carroll addresses metaphysics, he does so in ways that show he has failed to do his basic homework, and consequently blithely dismisses major traditions of philosophical, spiritual and religious thinking.

Let’s start with some basics. All the major religious traditions define God the creator as both transcendent (beyond the world) and immanent (within the world). In Carroll’s view, physics covers the world, whereas metaphysics is limited to the transcendent (the so-called “beyond” of the world). Since physics gives us the world, metaphysics becomes an uninvited and unwanted guest, a free-loader who distracts us from what is real.

Carroll presumes to address Aristotle and Aquinas, but he doesn’t identify or address Aristotle’s basic definitions of different kinds of causes. As a result, he vaguely presumes that Aristotle is simply explaining physical causes with some bigger cause that started it all (Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, which Aquinas revisits as the Uncaused Cause). More explicitly, he uses the following definition of “God” to make the case that we can do without God, and thereby understand reality solely through “natural” means of emergence:

For the sake of being definite, let’s imagine we’re talking about God as a person, as some kind of enormously powerful being who is interested in the lives of humans. (pg. 146)

He uses this kind of thinking to dance around issues of ontology and cosmology. When he actually gets down to arguing ontology and metaphysics, he doesn’t refer to Aristotle or Aquinas, or any widely recognized and respected representative of those traditions, but instead explores the ideas of William Lane Craig, a fundamentalist professor at an obscure evangelical seminary who is self-described as a “Christian apologist” and “analytic philosopher.”

[It’s not that I have anything against Christian apologetics per se: C.S. Lewis is a well-regarded and beloved example of the species. But C.S. Lewis was also a true thinker, and when life didn’t go along with his neat and tidy ideas, he got real about living with faith but without certitude. (His marriage to Joy Davidman late in his life, who recovered from and then succumbed to cancer, changed his view from that described in his book The Problem of Pain to the more mature perspective expressed in his pseudonymous book, A Grief Observed.) And as for philosophy, the analytic tradition is so formal and unimaginative that it is neither true to life nor phenomenologically credible.]What Carroll’s whole argument against metaphysics boils down to is a critique of William Lane Craig’s syllogism (which Craig tellingly names “the cosmological argument” rather than “the ontological argument”) (pg. 199):

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

- The Universe begins to exist.

- Therefore, the Universe had a cause.

Instead of challenging the metaphysical traditions of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism, Carroll decides to challenge the theological ideas of 19th century Deists, who thought of God as the Almighty, a force more powerful than any earthly or celestial force. But a force of the same order, none-the-less.

Sorry, but serious philosophers, metaphysicians and theologians do not think of God as the Big Guy who shoved us into existence, then generally ignores us because we are boring, yet still occasionally gets teed off at our antics and consequently yanks us around trying to straighten us out so we can eventually join him (properly chastened).

[If you think that is a ridiculous argument, consider the quality of argumentation Craig exhibits in one of his “public debates against an atheist” series (this seems to be his claim to fame). His debate with Shook comes down to the opposing positions of “You can’t prove the supernatural exists” versus “You can’t prove the supernatural doesn’t exist.” Even worse, Craig accepts for argumentation Shook’s analogy of buying stock on the stock market based on weak arguments that the stock market is going up. Craig not only accepts the analogy as valid (bringing Mammon into the Temple?), but thinks he wins the argument by claiming that Shook cannot prove the stock market won’t go up.]The metaphysics of the great religious traditions do not think of the First and Final causes as first and last in time, but first (primary) and last (ultimate) in order of significance. The ontological question is not limited to cosmological questions such as how the universe as we know it came to be. The metaphysical traditions were not based on a literal view of God as some “divine watch-maker” who fashions the mechanisms that determine the fate of everything in the universe, except when He, the super-man, decides to intervene. To them, reality was not just literally true, but was analogically true as well. They did not assume that religious texts were literal transcriptions of the thoughts of some super-man, but were metaphorical descriptions and probes into reality, history and the human soul. If Carroll wanted to take on a better representative of religious tradition, he would do better to review Robert Spitzer’s book New Proofs for the Existence of God: Contributions of Contemporary Physics and Philosophy (Eerdmans, 2010). Since modern physics has greatly expanded the range of physical causes, Spitzer shifts terminology from causes to types of being, such as conditioned and unconditioned.

But Carroll promises something more sophisticated than reductionism and fundamentalism. He proposes a physicalism and naturalism fashioned with poetic accessories that do not reside in the mechanistic, and therefore brutal, past, nor in the speculative, and therefore non-existent, future, but rather in an undetermined and ill-defined “present.” Searching for this hypothetical “present” proves frustrating: is it the “present” as in a theoretical point in time that itself has no duration? Or is it some perceptual present of neurological functioning that lasts fractions of a second, or the experiential present of consciousness, that lasts a few seconds (the “present moment” of mindfulness)? Or the “present” that we remember in relation to a situation, a “situational” present that might last hours, or days, or years (as in “I am presently engaged in completing a paper”)? Or the “eternal” present that some of our most favorite memories inscribe? To encapsulate all of these in the ways that Carroll suggests, making his “poetic naturalism” theory embrace past and future in his “naturalistic” and “poetic” “now,” suggests that he is a metaphysical poet without any philosophical reflection to back it up.

Back to the question of poetry in “poetic naturalism.” Carroll seems to treat “poetry” as a form of knowledge rather than imagination. He establishes criteria for determining when something imaginary is an illusion — if an “illusion” is involved, its truth value is discredited even if the truth value is metaphorical. Indeed, there are large genres of poetry that Carroll would presumably deny a role in “poetic naturalism”. Since he claims that reality is purely immanent without an element of transcendence, we should discount the metaphysical poetry of John Donne, the English Romantic poets (e.g. Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Yeats — who was influenced by Bergson’s Intuitionism) and their American counter-parts, the Transcendentalists (Emerson, Thoreau, Lowell). Add to this the ancient poetry of the Upanishads and the Psalms. We could go on and on — sorry, but if Carroll is going to include a whole area of study as part of his theory without doing his homework on the subject, he is not getting a passing grade from me.

How this crippled view of poetry affects his theoretical performance shows up in the following passage where he treats the evidence of human behavior as a distraction from the true aim of physics (a unified theory of everything), which must none-the-less put up with these nagging questions:

So we’re allowed to contemplate alterations in this basic paradigm of physics — but we should be aware of how dramatically we are changing our best theories of the world, just in order to account for a phenomenon (human behavior) that is manifestly extremely complex and hard to understand. (pg. 110)

What seems most poetic about Carroll’s theory is that he seems to be replacing the mechanistic metaphor of how the universe works with elegant mathematical formulae (his appendix is titled The Equation Underlying You and Me). This removes us from the gritty realities of gears grinding or running smoothly, and puts us more in the ethereal world of Platonic ideas, timeless and ever-present. But aside from Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle and the resultant particle probability calculations, mathematical formulae formulate closed systems with definite predictable outcomes. This is not poetry, which often attempts to articulate the ineffable — it is naturalism given poetic license to bask in some kind of illusory present that is self-creating.

Sorry guys, but the formalism of mathematical formulae is no different from the either/or closed systems generated by formal operations. Life is not like that, and the mathematical formulae themselves are aspects of consciousness, not determinants of consciousness. Consciousness will always be more encompassing than one of its aspects, no matter how elegant the aspect appears or operates. To say that the underlying, deep structure of reality is defined by mathematical formulae is to accept a “counting” (measurement) metaphor as the basis for both science and truth. Another metaphor can suggest a different perspective: the center or essence of reality. If we define reality as nature and nature as immanent, we still have not eliminated the question of the essential core of reality that makes it exist and have its nature. And there is no reason to exclude transcendence from this idea of a center, or essential core, of reality. At least this metaphor gets us farther than the basic “ground” metaphor: as we all know, a biological product like an apple has a “core” (where the seeds are), and this core is what makes the apple fertile and creative. What good is the ground if we cannot stand on it, reach up, and pick an apple? (Maybe we do need to talk about Adam and Eve.)

But Carroll’s poetic naturalism not only fails on the score of understanding human behavior, it lops off the most interesting aspects of physics itself. Carroll advocates the Core Theory of Physics (a general consensus of “normal” physics that includes general relativity and quantum mechanics), but admits that this does not generate a quantum theory of gravity. Carroll’s main claim to the primacy of physics over metaphysics is its unparalleled predictive success in laboratory experiments on matter and energy. Now we do not expect scientists to be super-human and have answers for everything, but the “things” that cannot be accounted for by the Core Theory are none other that Black Holes and the Big Bang itself (which, by the way, can’t be investigated in a laboratory):

We lack a full “quantum theory of gravity” — a model that is based on the principles of quantum mechanics, and matches onto general relativity when things become classical-looking. Superstring theory is one promising candidate for such a model, but right now we just don’t know how to talk about situations where gravity is very strong, like near the Big Bang or inside a black hole, in quantum mechanical terms. Figuring out how to do so is one of the greatest challenges currently occupying the minds of theoretical physicists around the world.

But we don’t live inside a black hole, and the Big Bang was quite a few years ago. (pp. 175-6)

Well, I don’t live in a black hole or near the big bang either, but a significant part of my interest in physics is our understanding of the nature and meaning of such cosmic wonders, What is the good of all this if we aren’t allowed to speculate in ways that mights include non-material explanations? I much prefer the questions raised by astrophysicist Lisa Randall (Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Universe’s Hidden Dimensions, Ecco, 2005, pp. 456-7), who summarizes the theories on the “non-local” and “extra dimensional” aspects of reality as follows:

Which, if any, of these ideas describes the real world? We’ll have to wait for the real world to tell us. The fantastic thing is that it probably will. One of the most exciting properties of some of the extra-dimensional models I’ve described is that they have experimental consequences. I can’t overemphasize the significance of this remarkable fact. Extra-dimensional models — with new features that we might have thought were either impossible or invisible — could have consequences that we might see. And from these consequences, we might be able to deduce the existence of extra dimensions. If we do, our vision of the universe will be irrevocably altered.

There might be tests of extra-dimensional spacetime in astrophysics or cosmology. Physicists are now developing detailed theories of black holes in extra-dimensional worlds, and have found that although they are similar to their properties in four dimensions, there are subtle differences. The properties of extra-dimensional black holes could turn out to be sufficiently distinctive that we will be able to discern recognizable differences.

We apparently have three metaphors concerning the nature of black holes: 1) the ravenous monster that eats and destroys everything in its midst (as in Dante’s Hell: “Abandon hope all who enter here” — or, if you do manage to escape, you will end up as nothing but a desiccated, cold, meaningless shell of your former self); 2) the distant and irrelevant outlier to the Core Theory with which you will never have a meaningful relationship; or 3) the entrance to an extra dimension (whether that dimension be a new creation, a reincarnation, or heaven). What we do know now is that mathematics supports the idea that black holes store information rather than destroy information (see Susskind’s book on his winning argument against Stephen Hawking).

Susskind reminds us about “wormholes” as ways a thing can exist at two places at once: they seem to exist, but nothing could get through them, not even photons, because they exist for very short periods of time and are very narrow (pp. 70-1). What he doesn’t answer is whether “bits” — information — could get through. But black holes exist outside the laws of time and space, so why would one need a “wormhole” to get anywhere, since all non-local events exist nowhere and the same place at the same non-time? So when Susskind disappoints us by saying we can’t go through wormholes to get to heaven or to hell (like in the Disney movie “Black Hole”), well, we don’t need wormholes to do that when black holes are perfectly capable of doing so without them. And if Hawking were right and black holes destroy information, then that would be like hell — everything boringly the same and without spark or spirit. So if information destruction can be like hell, why can’t information gathering be like heaven? If nothing else, it would certainly be more interesting.

To summarize, there are three basic types of emergence theory:

Weak emergence: The laws of the micro systems accumulate to establish laws of the macro system with no change in basic principles (the whole is the same as the sum of its parts). [Example: scientific materialism, aka “scientism”.]

Strong emergence: The macro system has laws of operation separate from the laws of the micro systems. You cannot derive the macro laws from the micro laws (the whole is greater than and separate from the sum of its parts). [Example: religious fundamentalism]

Moderate emergence: micro is potential, pre-macro. Whole integrates parts and is different than sum of parts, but not independently so. [Example: neo-thomistic philosophy]

Carroll’s definition of emergence is a weak version, where consciousness is not a unique phenomenon but is rather a product of physical brain functioning. This position does not allow for consciousness to be a united experience. Instead, consciousness is subject to the various brain functions that wax and wane, each with its own “personality” that competes for dominance in a “parliamentary system.”

Now I will explore some of the issues Carroll covers to show how, when he goes off the core theory reservation, he gets life and consciousness, as well as the fundamental nature of reality, wrong. My approach is one of moderate emergence which retains a traditional idea of the soul — let us see how many ways Carroll sucks the soul out of life and consciousness. The italicized headings are titles to chapters in Carroll’s book:

Are Photons Conscious? Carroll argues that “quantum entanglement” has nothing to do with consciousness and that consciousness is a product of brain waves. In this sense nothing in reality is conscious — reality only creates the appearance of consciousness. A moderate emergence theory does not conclude that protons are conscious, but rather “pre-conscious.” They become part of consciousness when they are involved in awareness. In this sense, matter is not life but “pre-life”, life is not consciousness but “pre-consciousness”, and consciousness is not bliss but “pre-bliss.” By becoming situated in consciousness, the photon becomes other than itself.

What Exists and What is Illusion?: Not everything is real, even by this permissive standard. Physicists used to believe in the “luminous aether,” an invisible substance that filled all of space, and which served as a medium through which electromagnetic wares of light travelled. Albert Einstein was the first to have the courage to stand up and remark that the aether served no empirical purpose; we could simply admit that it doesn’t exist, and all the predictions of the theory of electromagnetism go through unscathed. There is no domain in which our best description of the world invokes the concept of luminiferous aether; it’s not real. pg. 111

Here is an example of where Carroll’s literalism diminishes his metaphorical abilities. Before Newton, the “luminous aether” was a theory held by most natural philosophers to account for how light travels through space (a “conductor” of light, as opposed to an “insulator”, so to speak). Newton’s mathematical calculations on the movement of objects, describing gravity’s effects through “empty” space eliminated the need for this “aether” to describe the movement of objects. Newton’s calculations are true “for all practical purposes” until you get to the phenomenon so rare to our everyday experience that Einstein predicted and helped discover. Einstein’s calculations also made the “aether” unnecessary since he showed that electromagnetism and photons are not just waves, but elementary particles as well. [Although Einstein conceded that a version of the aether could exist, it was just not necessary for his calculations.] This seems to be where Carroll stops his historical account.

Since then we have had the Higgs Discovery established by the CERN collider team (2012 — see Lisa Randall’s The Higgs Discovery). Although Carroll makes mention of the Higgs Boson, and separately speaks of the “quantum vacuum fluctuations”, he makes little of these phenomena. But if you read Randall, you find that without the Higgs Field, electrons would have no mass and consequently there would be no weak force to involve them in making atoms. So much for electricity existing without an “aether.”

Furthermore, without the Higgs Field, how could light travel through “empty space”? It probably can’t, since there is no such thing as “empty” space. In Void: The Strange Physics of Nothing, (Yale, 2016), James Owen Weatherill reminds us (pg. 113):

If we recall that particles are just a particular kind of phenomenon that fields can exhibit in quantum field theory, the vacuum state just represents the field configuration where we minimize the particlelike phenomena. But there is no configuration where we can force them to go away altogether.

Weatherill echoes Lisa Randall’s explication of “virtual particles” (Warped Passages, pp. 225 – 233) in the following passage (pp. 114 – 115):

This suggests that a pair consisting of an electron and a positron is “equivalent” to a situation with no particles at all: the matter and the antimatter effectively cancel one another out in the overall accounting of the amount of stuff in the universe.

In a classical theory, this would not work out, since electrons and positrons both have mass and energy. But vacuum fluctuations provide the little boost of energy necessary for an electron/positron pair to spontaneously pop into existence, travel along for a little while, and then meet again and wipe one another out. The particles created in this way are sometimes called “virtual” particles because, like vacuum fluctuations themselves, they have a kind of indefinite, ethereal nature: they come and go in an instant, little blips on the background that are never really there. But they can sometimes influence other physical processes.

The scenario that both Randall and Weatherill describe is one where say a photon travels through space not on its own energy alone, but with the aide of the Higgs Field and its attendant energy and particles flows. So if we ask “how does a photon travel 11 billion light years through space to be detected by our telescopes and satellites? The answer is “with a little help from a lot of their friends” (both actual and virtual).

There is a role for poetry in naturalism, but it is much more evidenced by Lisa Randall than Sean Carroll. Randall as a truly poetic physicist: she uses human and animal examples as analogies for physics phenomenon, and song lyrics to represent physics principles. If you read Warped Passages, you will find that each chapter is headed by a song lyric, and astrophysics principles and processes are explained by analogies and metaphors of human and animal characters.

There are various other details of Carroll’s treatise that I would like to cover, but for now I will end with and interesting divergence between Carroll and Randall over “dark matter” (which, along with “dark energy” accounts for the vast majority of the “stuff” in the universe). Carroll’s book came out in 2016, and in it he states:

Whatever dark matter is, it certainly plays no role in determining the weather here on Earth, or anything having to do with biology, consciousness, or human life. (pg. 183)

The same year, Lisa Randall published her most recent book entitled: Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the Universe (Ecco, 2016). In it she puts forward a theory (based on new calculations of dark matter) that there is a dark matter “halo” around our solar system, and that a “diaphragm” associated with it may be destabilizing the Oort Cloud periodically, thereby causing the asteroid and/or comet impacts that have resulted in mass extinctions in the history of life on Earth. If she is right, then without dark matter, life and consciousness as we know it would not exist.

In the end, I would not endorse Carroll’s thesis with the title The Big Picture, but rather would title it The Slice of Reality Relevant to Popular Electronics. As an apologist for the Core Theory, he commits what Karl Popper referred to as “promissory materialism”, which is an on-going pattern in “scientism” that promises a theory of everything based solely on physical principles. To me, the “promise” of a material closed system is not as promising as an open system that acknowledges the fundamental mysteries of being, life, consciousness and bliss.