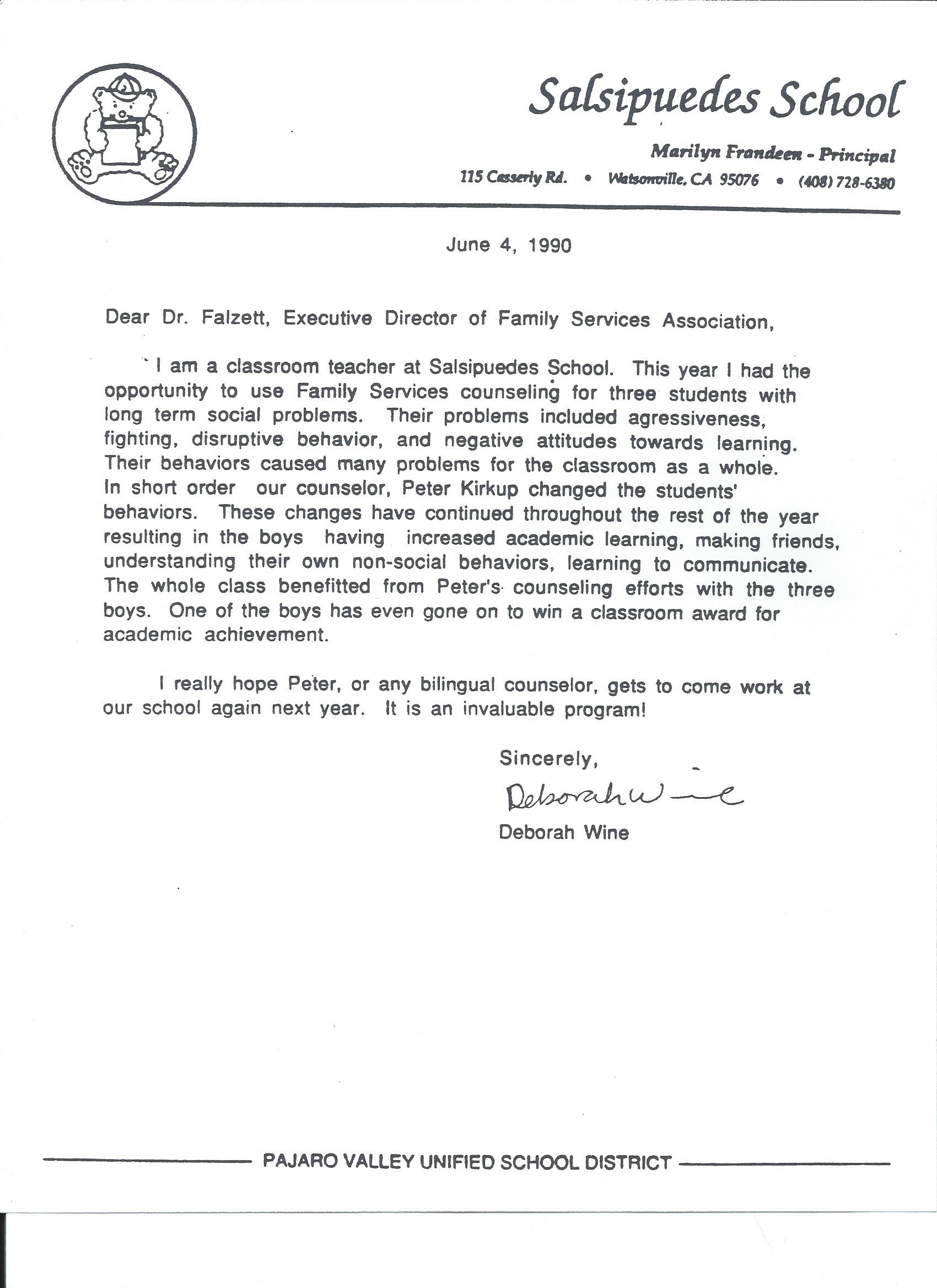

I developed this program in 1990 while on contract with a school in the rural Watsonville (CA) area. School staff wanted help with aggressive Spanish-speaking boys 8 to 10 years old (the other program on campus didn’t have Spanish-speaking capacity). Most programs at the time were based on the theory that all behavior problems of children were caused by low self-esteem and encouraged more “self-expression” rather than “self-control.” This approach met with immediate success and acclaim (see teacher’s letter at end of page). I used this program throughout my career working with impulsive boys in school settings.

Equipment needed: stop-watch, tennis ball, white board and markers, graph paper.

A full size sports stop-watch helps children manipulate and focus during the anticipation exercise better than a digital watch. Note the time: 4 seconds and 72/100ths, 28/100ths short of 5 seconds.

You know what a tennis ball looks like — this is a “kush ball”, an alternative which is easier to catch for smaller children and fumbly fingers.

Impulse-Control Training for Pre-Adolescent Males

Peter A. Kirkup, LCSW

Introduction: The Contract

Disruptive and aggressive behaviors are the most common impulsive behaviors that cause concerns for parents, teachers and peers. There is a practical value to defining these behaviors as impulsive because their common feature is a lack of delayed gratification. This is true regardless of whether the behaviors are motivated by anger, fear, or selfish greed.

Research shows that aggressive behaviors do not go away by themselves – aggressiveness is not just a “phase” or a matter of “boys will be boys.” Unless a concerted effort is made, aggressive and disruptive behaviors won’t diminish or go away.

The first consideration for developing a “concerted effort” is to develop a common cause among the most important adults in the life of the relevant children. Anti-bullying programs at schools have shown that connecting timid children with a culture of caring can help develop the confidence that goes along with a safe environment. All too often, too much attention and rewards go to the intimidating child, leaving intimidated children neglected and insecure.

Effective interventions for the intimidating child are based on good working relationships between the adults. When adults fight about the behaviors of children, children will live in an insecure social environment that reinforces intimidation and timidity. When children see the lives of adults as full of conflict and continual harassment, they believe what television tells them, that adults are dolts, that kids are clever, and that there is no good reason to grow up.

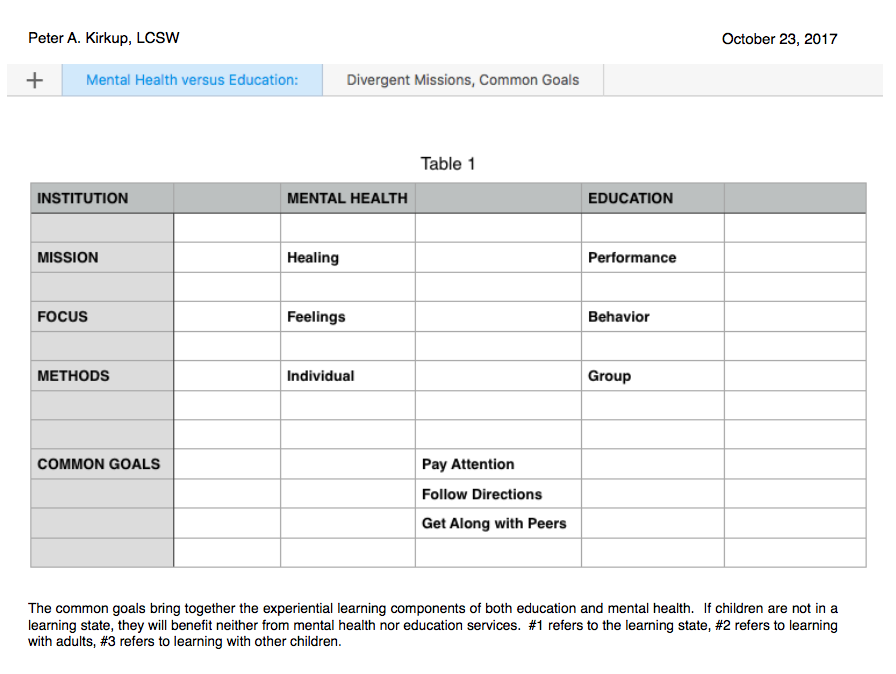

So the first task of intervention to reduce disruptive and aggressive behaviors is to establish common goals between parents, teachers, social workers, and other relevant adults. Most parents and teachers would agree that they want the impulsive child to do better in three general areas: 1) paying attention, 2) following directions, and 3) getting along with peers. Impulse-control helps children be ready to learn and relate in an acceptable way to adults and peers. Related goals that parents and teachers might want for impulsive children include calming down, taking time out, controlling temper, walking away from a fight, taking “no” or “later” for an answer, sharing, taking turns, solving problems and resolving conflicts. These are more mature and “manly” behaviors than the immature behaviors of picking fights, calling names, temper tantrums, yelling and demanding immediate gratification.

Once the social worker has defined common goals that the adults have for the children, the contract for work is established. The contract should not be a secret to the child and the child should not be left guessing the reason for meeting with the social worker. It can help for the parent and the teacher to tell the child the reason for meeting with the social worker before the first session.

Extrapolated from a chart by Robert Ayasse, LCSW, NASW-CA Annual Conference,, Oct. 2017.

The First Session: Framing and Reframing

Upon first meeting the child with a handshake, a greeting and introductions, it helps for the social worker to ask the child about the child’s understanding of the reason for him to meet with the social worker. Sometimes parents and teachers fail to talk to the child about the sessions, sometimes they do not make the reason sufficiently clear to the child, and sometimes the child fails to understand what he is told or is reluctant to admit his understanding. If clarification is needed, the social worker should inform the child of the contract established with the parent and teacher (using exact words to the extent that they are helpful) and should check back with the relevant adults to communicate that the child understands the expectations of the adults.

Once the frame of the contract is clarified with the child, the social worker can start in on the engagement and reframing exercises. For these exercises, the social worker needs to have hidden in a drawer a stop-watch and a tennis ball, and a marker board on the wall.

The lead-in for the reframing exercises is for the social worker to lean forward and ask the boy “How strong are you?” Invariably the boy will nervously answer “kinda strong.” Impulsive boys will not identify themselves as weak and the uncertainty of the situation militates against saying “very strong.” (Arm-wrestling with a larger, stronger male would embarrass that claim real quick.) If a boy says he’s real strong, don’t arm-wrestle him, but ask him to rate himself on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being someone huge like Hulk Hogan. The boy will immediately identify himself as a “less than 10.”

After he says he’s “kinda strong,” or an “8”, then say “Let’s see,” and reaching into the drawer, clasp the stop-watch, and draw the arm around to the boy. At this point he will think, “Oh-oh, now he’s going to arm-wrestle me.” Instead, to his relief, you will ask him, “Do you know what this is?” Most kids know what a stop-watch is and how it keeps time for races and other things. Show him how it works, where the start and stop buttons are.

Next you tell him that you are going to start the stop-watch and try to stop it as close to 5.00 seconds as you can. Stop it before it gets to 5.00 (e.g. 4.87) and write this number up on the marker board. Ask how close it is to 5.00 by subtracting the 4.XX number from the 5.00 goal.

Now it’s his turn. Give him enough chances to get close to 5.00, but make sure you catch him doing well by stopping it before it gets to 5.00. Write his 4.XX number up on the board, have him do the subtraction, and compare his close score to yours, asking which is closer and by how much.

Now ask him why he stopped the watch before it got to 5.00. Children will use similar explanations to express the same concept. If the child is having difficulties explaining this, have him try waiting until he sees the watch get to 5.00 before pressing the stop button. The time will invariably go way beyond 5.00 under these circumstances, and the boy will get the point that he stops it before seeing 5.00 because the stop-watch goes faster than his reflexes and he has to anticipate the approach of 5.00. Once the child articulates some form of the concept, label it “anticipation,” and write the word up on the board.

In effect, you have reframed “strength” from “force” to “timing and mastery” in a way that has engaged the child’s senses, muscles, thoughts and feelings. The boy may have various ideas about how “anticipation” can help in life. But don’t go too far into it now because you have another exercise to do.

Next, you shift back to your drawer and toss the tennis ball over your shoulder. The boy will react and probably catch the ball. Put up one hand and request that he toss it to you “right here.” Catch it with one hand and have him do the same, putting the ball “right there.” If the child is too young or his hand is too small for a tennis ball, use a “koosh ball” (the one with rubbery strings, which is very easy to catch with one hand).

See how many times you can toss it back and forth, catching it with one hand without dropping it. This is a cooperative, team challenge.

Now ask him what would happen if he waited until he felt the ball hit his palm before he closed his hand down on it. If he doesn’t recognize that it would bounce out before his reflexes could snag the ball, have him try. Get him to explain why this is. Talk about it enough until he can understand that it is the same as with the stop-watch – he has to anticipate its arrival and close his hand down on it as it enters his palm.

Timing is everything.

Not only have you demonstrated that mastery and self-control are more important than force, you have developed a challenging and engaging interaction that elicits cooperative, team-oriented reciprocity. You are targeting his strength (palm) and he is targeting your strength in a pattern of “in-fielder” reciprocity (“triple-play!”).

Marking to Impulse-Control

With the basis of the reframe established, now you can branch out into extended areas of mastery. One area is visual-spatial, and can be a good avenue for students with a good sense of proportion. Go to the marker board with the student, each picking a favorite color marker. Ask him if he knows what an “equilateral triangle” is. Point out the etymology of the word while writing it on the board: “equal” meaning the same, “lateral” meaning side (“lado” in Spanish means “side” as in “al otro lado”, the other side, or in football, a lateral pass is a pass to the side); triangle = three angles (like tricycle means three wheels). Go to the board and mark three points at equal distance, forming the three points of the corners of an equilateral triangle. With the edge of a piece of paper and pencil, measure the distance of the three sides from one corner of the paper, noting the “margin of error” in your triangle. Have the student do the same. Observe how he does it – impulsively? hesitatingly? does he over-correct, erasing and remarking points with his nose to the board? This will indicate his sense of proportion and eye-hand coordination. Check his margin of error. If he has a talent for this, it is a good strength to build on.

I once worked with a Spanish-speaking student who was quite disoriented in class even though he had a bilingual teacher. But the teacher noticed that he was good at sketching during their art-circle time. He was very good at this triangle exercise. I asked him to pick a pattern that we would copy. He picked a badge with the Batman symbol on it. Using graph paper, we measured all of the features of the pattern (starting with the oval in which the bat-shadow resides), expanded it three-times, and copied it on graph paper. I did my sheet and had him copy me on his sheet. We wrapped some graph paper around a ruler, measured the width of the oval, timed by three, the height of the oval, timed by three, mapping each step on the graph paper, where the ears hit the oval, times three, etc., etc. The whole pattern took us five half-hour sessions. He was integrating his natural sense of proportion with complex geometrical math and having success. He became much more oriented to what was going on in class.

Graph paper wrapped around a traditional ruler used to measure proportions and transfer to graph paper.

Posturing for Impulse Control

Many approaches to anger management emphasize the cognitive aspect of self-statements during conflict situations. Many of these techniques are varieties of the use of a self-time-out, where the individual attempts to cool off during the heat of the moment. Examples of these cognitive techniques include “counting to ten” (or counting backwards), or even carrying a card with options other than fighting, such as “just walk away.” These techniques can be helpful, but are often too weak to overcome the compulsions of behavior escalation.

If during a conflict escalation, an impulsive individual signals fight or flight by his posture, the outcome can be all too predictable. Regardless of the private thoughts of the individual, the fight or flight postures signal either threat of aggression or fear of vulnerability. Neither of these postures and signals lend themselves to evoking interactions that “cool down” the situation. Therefore, training how to posture non-aggressive strength and mastery in conflict situations can be more effective in changing problematic interactional, as well as cognitive and emotional, patterns. In the same way that some schools of acting find that the best route to taking on a character is to take on the unique and defining mannerisms of the character, sometimes the best route to developing a mature attitude is to take on a mature manner.

The following case example shows how specific training in posturing can fit into the larger contractual relationship established between parents and teacher.

Jimmy was a 4th grade student who was continually disruptive in class due to what he claimed was persecution by other boys who were Spanish-speaking. The teacher was not convinced of Jimmy’s account of what happened leading up to his disruptive behaviors, but was unsure because much of what was alleged happened when her back was turned. Because of the complexity of the situation, I did a classroom observation and scheduled a home visit after speaking with the mother over the phone. In class, Jimmy appeared to be immature, easily distracted, and often wandered aimlessly.

I then went to the family home and spoke with mother about Jimmy’s situation and possible options for addressing it. After some time, father appeared, obviously having listened in without my knowledge. I greeted father and expressed the wish that he had been present from the beginning so that I could get the full benefit of his input. Father expressed the view that his son was being persecuted by the Spanish-speaking boys and that his son was getting in trouble because I didn’t speak Spanish and therefore was not addressing the other boys’ behaviors. I assured father that I speak Spanish and had no intention of excusing the behaviors of others, but that there were ways his son could help stay out of trouble and make sure the trouble-makers were the ones getting the consequences for their behavior. It was apparent to me that father was prejudiced and may be contributing to his son’s exaggerated sense of persecution. At the same time, it did not seem to me to be productive to try to address this directly.

With the contract to help Jimmy stay out of trouble that he didn’t deserve, I proceeded to meet with Jimmy. I first went through the standard impulse-control exercises described at the beginning, using stop-watch and tennis ball. These interactions confirmed my sense of Jimmy’s immaturity. Jimmy complained about how the Spanish-speaking boys were constantly trying to “mess with” him and get him “in trouble.” Jimmy stated that the other boys should be getting in trouble, and agreed that he wanted to find ways to stay out of trouble.

I then asked Jimmy to show me how he showed other boys “don’t mess with me.” Jimmy had no idea of how to do this. I then asked him to stand up and fold his arms. When Jimmy did this, his feet were pigeon-toed, his knees were turned in and touching, his arms were cradling his tummy and he was slightly leaned forward. In other words, he looked like a girl protecting herself from the cold – not a very effective “don’t mess with me” posture. I then had him turn his feet and knees outward with his legs slightly apart, lean slightly back and lock his arms across his chest with his elbows pointed out. I explained to him that this posture showed that he was ready to deal with whatever happened without being too ready to fight or flee.

After anchoring this posture, I arranged with the teacher to set it in the classroom context. The teacher agreed to allow Jimmy to move from his seat to the classroom door anytime he thought that someone was trying to “mess with him.” His seat was close to the door and there were no seats behind him, reducing his concern over what might be happening behind his back. He was able to move from his seat to the door with his back to the wall, and then could stand at the door with his “don’t mess with me” posture.

Once this arrangement was established, Jimmy never seemed to need to use it. Apparently everyone stopped messing with him.

Certain elements of the “don’t mess with me” posture are important for helping people to “back off.” Folding the arms and leaning slightly back prevent leaning forward ready to pounce with arms out and available to attack.

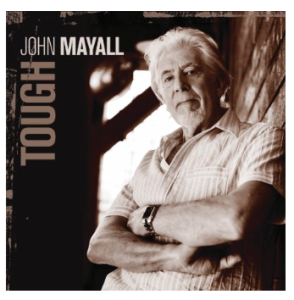

A good depiction of this stance can be found on the cover of John Mayall’s record “Tough” (2009):

Below is a review by a teacher of the results of these interventions:

As recently as 2016, a former student and intern of mine wrote of this training: “I still use many of these [techniques] with the many kids working on this skill.” David Lewis, LCSW (12/24/16 email).