This article is dedicated to Cary Cochran (1949 – 2016), PhD psychologist, musician and master of the Open Center model of Family Education. A version of this article was presented and discussed at an Open Center at the Tower Theater in Marysville, CA. The training room there is now called the Cary Cochran Open Center Training Room.

In the age-old debate over nurture versus nature (environmental influence versus biological determination), research studies over the decades have come to different conclusions. Some studies concluded that 60% of behavior is determined by biology and 40% by environment, while other studies concluded that 60% of behavior is determined by environment and 40% by biology. What accounts for the differences/overlap?

Pre-natal environment and epigenetics have been found to also play significant roles, probably accounting for the 20% divergence. Included in these factors are circumstances such as: Did father smoke tobacco while he was going through puberty? Was mother healthy and happy during pregnancy, or was she stressed and abused? Did mother drink excessive alcohol during pregnancy?

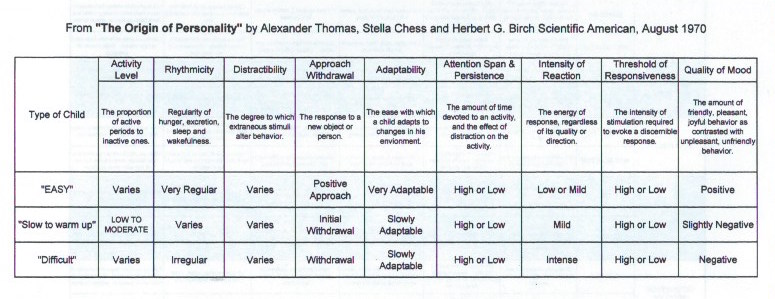

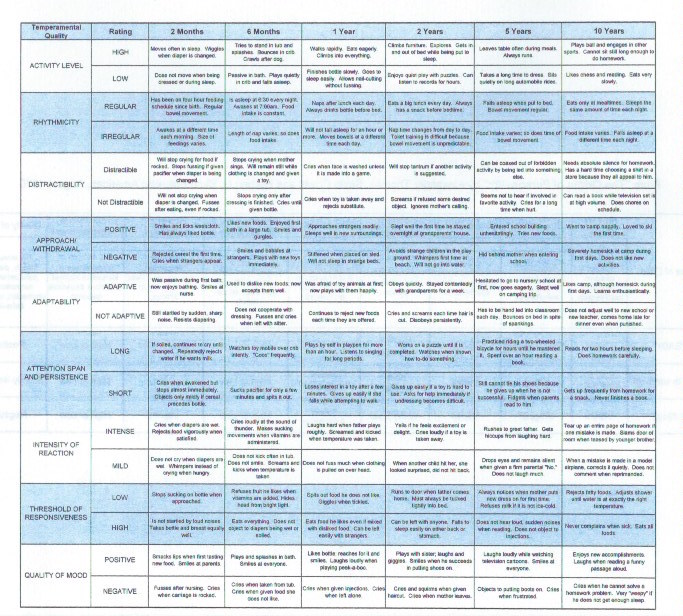

Biological genetics, epigenetics, and the mother’s personal and social emotional climate make up what is called “congenital,” or what the infant is born with. A well-researched term for this is “temperament,” which describes behavioral styles and tendencies across behavioral variables. In the first decade of their longitudinal study (Scientific American, 1970), Thomas and Chess identified 9 variables, including activity level, rhymicity, etc.

Reformatted from Thomas and Chess 1970, 9 temperament variables with examples of behaviors over the first ten years. Probably too small to read the small print, but it conveys the ideas. For a readable version, click here.

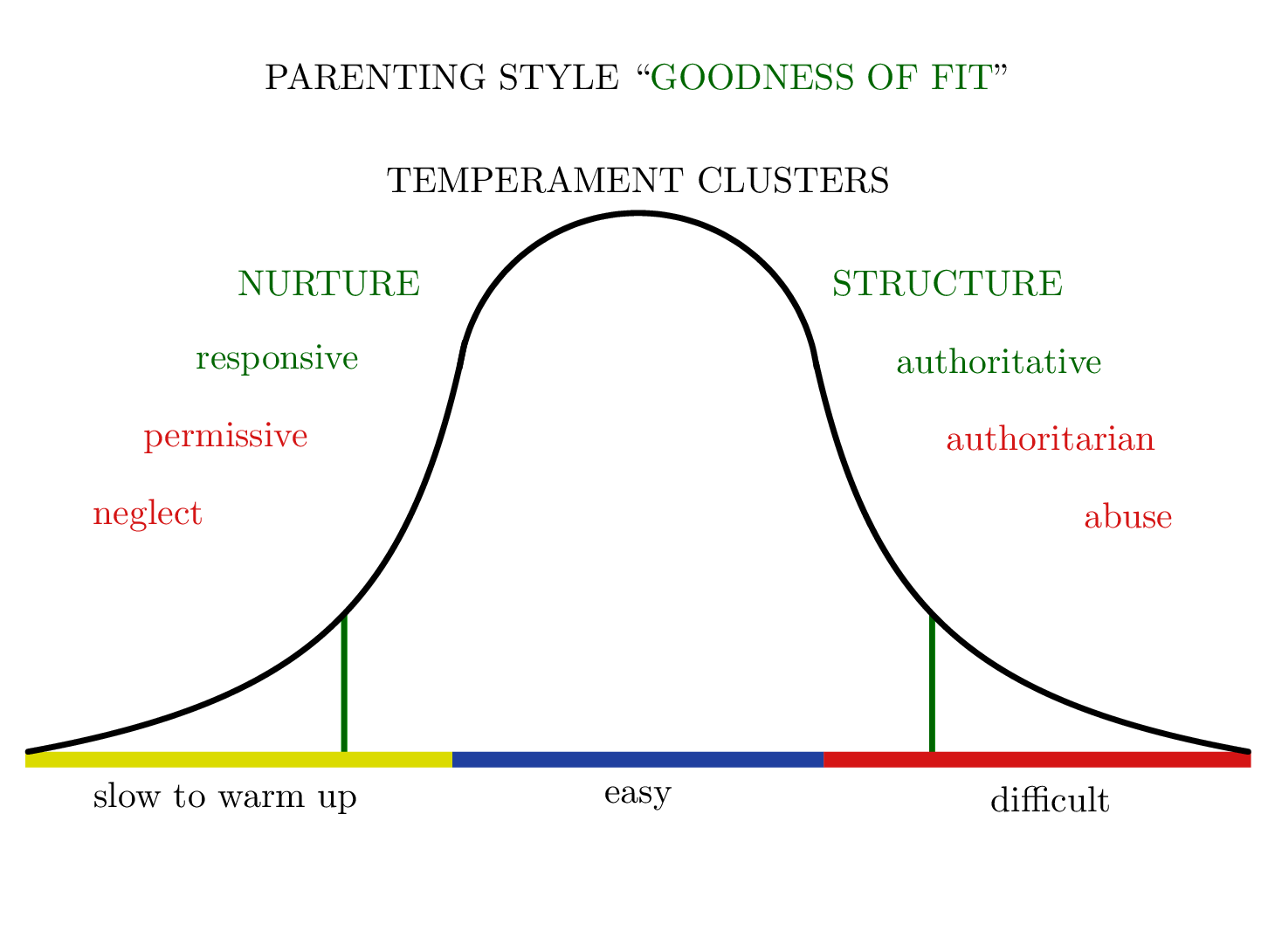

65% of children cluster into one of three temperament clusters: easy (40%), difficult (10%), and slow-to-warm-up (15%) (Temperament and Development, Bruner/Mazel, 1977, pg. 23). Easy temperaments are the most resilient and adaptable; difficult temperaments exhibit behavior excesses and impulsivity, while slow-to-warm-up temperaments exhibit behavior deficits and withdrawal. (For a survey on temperament, click here for Donald Saposnek’s useful tool.)

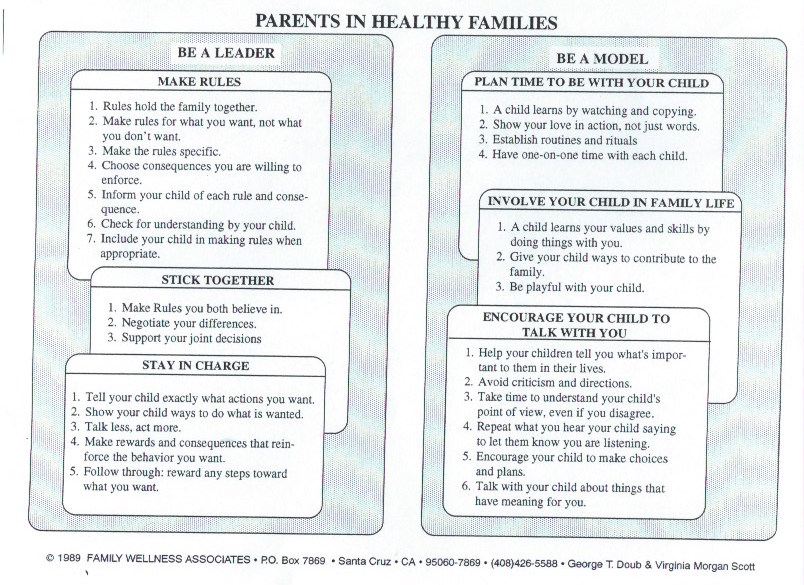

What Thomas and Chess found with further research is the importance that the parenting style is a “good fit” with the child’s temperament to induce optimal development (Know Your Child, Basic Books, 1987). Their description of parenting styles is consistent with the roles of parents defined by Structural Family Therapy. Below is a popular depiction created by the Family Wellness Associates:

When presenting this to family groups, Virginia Scott and George Doub would describe the two basic roles of a parent as “be a leader and be a lover.” In other words, provide both nurture and structure. Other terms used in the family therapy literature for these positive differences in response style are to be authoritative and responsive. Slow-to-warm-up children need an extra dose of responsive nurturing (without being permissive or neglectful), while children with difficult temperaments need more of the authoritative structure (without being authoritarian or abusive). [Notice how over time, these extremes can reverse: abusive parents give up and become neglectful or permissive; permissive parents can get fed up and finally react abusively.] Put on a bell curve, with easy temperament in the middle and less easy temperaments on the sides, looks like this (my rendition):

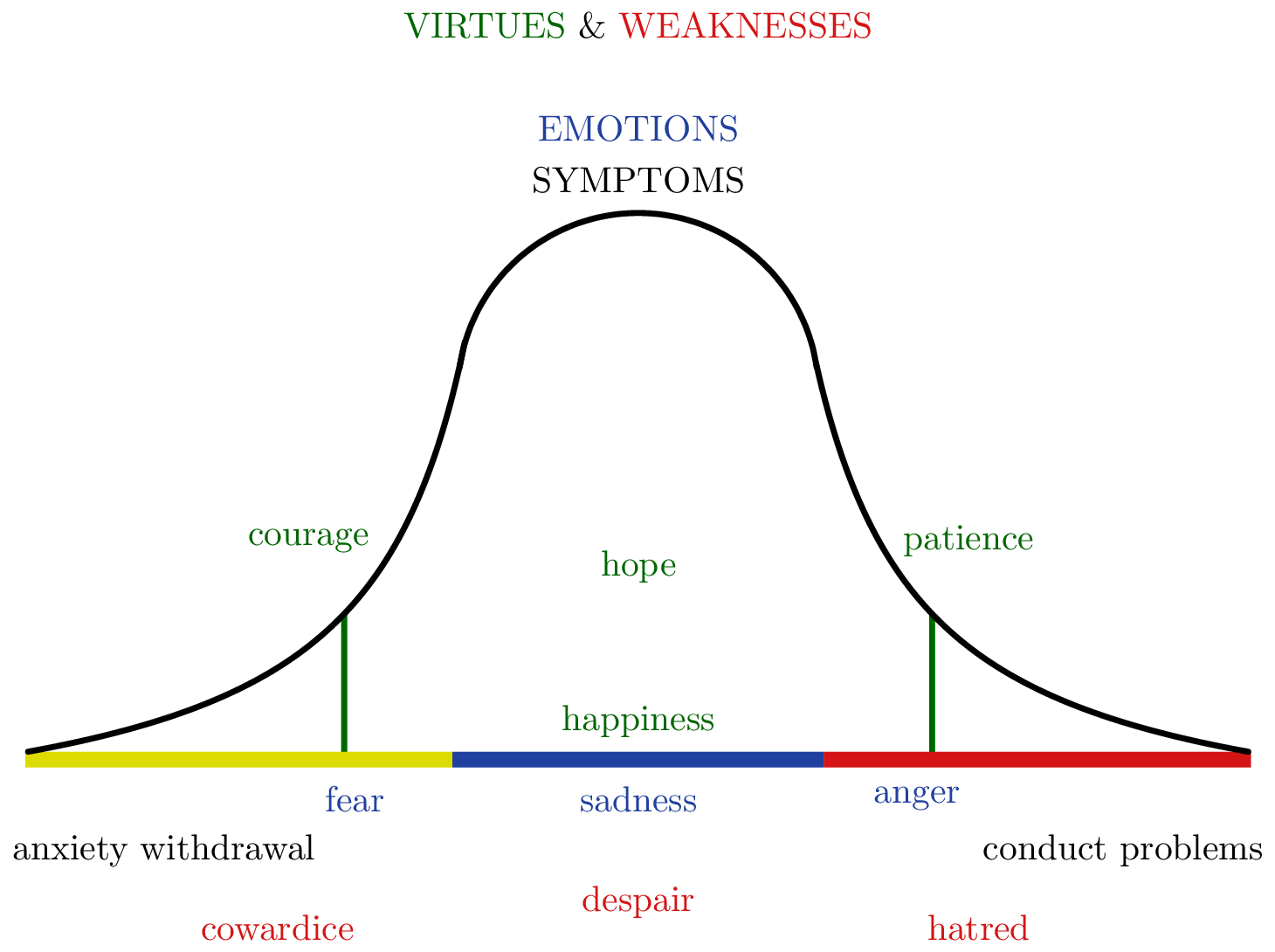

A different way to view the same bell curve is based on human emotions. Sadness and happiness are the most human of our emotions (mammalian), while fear and anger are associated with the fight or flight instincts that we share with other animals (reptilian). Slow-to-warm-up children are generally more anxious and withdrawn, while children with difficult temperaments tend to be more aggressive and angry. The terms “anxiety withdrawal” and “conduct problems” comes from the RBPC (Revised Behavior Problem Checklist), an assessment and outcome measure for parents and teachers to measure children’s behaviors before and after an intervention (we used it in the Families and Schools Together — FAST — program). If you reduce anxiety withdrawal or conduct problems, the child’s behavior has moved from the dysfunctional extremes into the more mainstream and functional give-and-take of harmonious social life.

These concepts help us better understand the roles of nature versus nurture as determinants of our behavior. But is this all? (This was my routine question to my students at this point in the training. Not one student came up with an answer, but they were sitting on the edges of their respective seats, fearing that there was some obvious answer that they just couldn’t see. And they were right!)

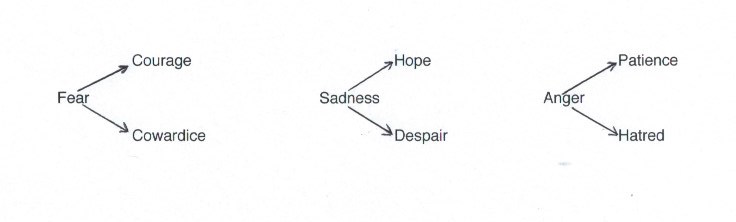

Of course not. We also have something called “free will” that increasingly guides our behavior as we get older. (In his book Willpower (Penguin, 2011), Roy Baumeister shows how glucose is necessary for exercising good judgment while making decisions, whereas when people’s blood sugar gets too low, they tend to make stupid mistakes.) Relating this back to our basic emotions: our temperament and stress level tend to dictate how much we are subject to fear, anger and sadness, but our free will dictates how we respond to these emotions in our lives. When faced with fear, we ultimately have the decision about whether to cower in cowardice, or to “panic later” and over-ride our fear with courage. When faced with anger, we either decide to sink into hatred, or take a deep breath and proceed with patience. And when faced with sadness, we can either spiral into despair, or seek out sources of comfort and hope.

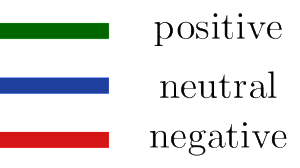

The last two depictions below put value judgments on the things we can control: our responses to emotions and our parenting styles. Green means “Go for it!” and red means “Stop it!” The emotions are neutral in that we all have them and can’t help it, so they are in blue. It is how we deal with our emotions that either help us or hinder us from developing our savoring and coping skills.

Now for some examples. I started to develop this training when I was a trainer for the Families and Schools Together (FAST) program (it is a multi-family group program held at schools with family and dyadic activities designed to increase parent-child bond and family cohesion). When the families are at their respective tables, they play a couple of adult-led turn-taking games. While turn-taking, the difficult temperament children will tend to interrupt (or disrupt) others, taking the spotlight and other people’s turns. The slow-to-warm-up children will tend to withdrawal and dodge their turns. In the extreme, hyper Jill will be running around the room disrupting other families, while anxious Jack will be hiding under the family table.

Now for some examples. I started to develop this training when I was a trainer for the Families and Schools Together (FAST) program (it is a multi-family group program held at schools with family and dyadic activities designed to increase parent-child bond and family cohesion). When the families are at their respective tables, they play a couple of adult-led turn-taking games. While turn-taking, the difficult temperament children will tend to interrupt (or disrupt) others, taking the spotlight and other people’s turns. The slow-to-warm-up children will tend to withdrawal and dodge their turns. In the extreme, hyper Jill will be running around the room disrupting other families, while anxious Jack will be hiding under the family table.

The goal of the turn-taking activities is for the program team members (which includes a program graduate parent partner who is a paid team member) to help parents manage the turn-taking activities. Team members do not step in and take over, but use the power of numbers to assist the parent in being empowered with their families. So when Jill runs off, we don’t go to get her (she is likely to scream “What are you doing to me!” and get their parent angry with you), we instead ask mother if she would prefer us to get Jill or if she would like us to set with the rest of her family while she gathers up the darling.

Here is a link to a mother giving the low-down on her approach to being a parent. Notice that she probably has herself locked in a room with ice cream, wine, and an activity to entertain herself. Her children are not going to get the better of her, but she knows they will come around (hey, she has the car keys, so what else do you need to know?).

One of my favorite people to talk with about these ideas was the late Dr. Cary Cochran, Adlerian psychologist and master MC of the Open Center Family Education Model. The main skills for operating the Open Center are: active and flexible understanding of birth order dynamics, the goals of mistaken behavior, methods of encouragement, and an ability to engage and manage audience input (including heckling). Cary was one of my favorite joking partners until he died at age 66.

My wife introduced me to a comic saga by Helen Cresswell about the Bagthorpe Clan (in 9 volumes). Cary read the first 3 volumes and considered Cresswell the best author he ever read because of her imaginative description of the sibling rivalries and unpredictably predictable results of poorness of fit in parenting. So for those interested, I am going to illustrate the concepts of this paper through a condensed version of the Bagthorpe saga, showing how Cresswell’s keen insights into family dynamics make her series unrivaled and much imitated.

The Bagthorpe Clan: Temperament and “Badness of Fit”

Here is a depiction of the characters, starting from the upper left hand corner and proceeding clock-wise: Billy Goat Gruff, Daisy Parker, Celia Parker, Russell Parker, Thomas the Cat, William Bagthorpe, Rosie Bagthorpe, Zero the dog, Laura Bagthorpe, Jack Bagthorpe (in the middle between his parents), Henry Bagthorpe, Grace Bagthorpe (“Grandma Bag” to Daisy), Alfred Bagthorpe, Mrs. Fosdyke (“Fozzy”, the Bagthorpe cook), Tess Bagthorpe, and back to Billy Goat Gruff (who keeps showing up like a bad penny).

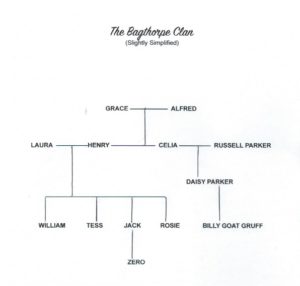

This family tree includes the main characters driving the action at the Bagthorpe and Parker residences. Henry and Laura live with their four children, and Henry’s parents, at Unicorn House. Henry’s sister Celia lives with her husband and daughter at Knoll House. Celia never leaves Knoll House, but Daisy and her goat are always making their way to Unicorn House, much to the chagrin of Henry and the delight of Henry’s mother Grace.

Grace and Daisy are known at Unicorn House as the “Unholy Alliance” because Grace is constantly praising Daisy and the goat while they proceed to provoke, annoy and destroy everything in sight. Grace’s overriding purpose in life is to create drama and enjoy the spectacle, and the easiest way to do this is to goad her argumentative son Henry into a bad temper and impulsive behavior, and the easiest way to do this is to use Daisy and the goat to get Henry’s goat and find some pretext to get the police involved, get them into her confidence, and get Henry arrested.

In order to get to the temperament and fit aspects, a thumbnail sketch of each character and the overall plot dynamic, is in order.

The Bagthorpe family is dominated by a majority of narcissistic extroverts, driven primarily by “Grandma Bag” (Grace — this is Daisy’s pet name for her grandmother, and in order to deem Daisy a sweet and innocent and creative child, Grace puts up with this). The main recurring action is Grace’s attempts to make her son Henry look bad, get into trouble, and the ultimate thrill, get him arrested. When she can’t goad Henry into action (Henry knows she is trying to do this so will often lock his jaw to avoid a Row), Grace deploys Daisy and Daisy’s various weapons, most of whom are real and generally animals of various species that she loves to set free and get them to perform.

The other narcissistic extroverts define themselves by their Strings to their Bow (same as feather to their cap). These are self-proclaimed skills and talents, sometimes raw and undisciplined, that each sibling uses to upstage the others, prove themself the genius that would be rich and famous if only the media would cooperate in promoting them to their adoring public in waiting. So in descending order, the Young Bagthorpes (YBs) talents are:

William: Short-Wave Radio, communicating with Anonymous from Grimsby (who communicates with extra-terrestrials and UFOs, sporadically sharing his knowledge with William); drums (helps make a lot of racket when the YBs are conspiring to get rid of an unwanted guest).

Tess: Violin, oboe, and French. (The violin is the leading metaphor for the strings and bows, but it also makes a lot of racket for the same purpose as above.)

Rosie: Portrait painting, mathematics. (She may be the most talented, but being the youngest, she follows her older sibs leads).

Then there is Jack, the middle child, who is considered ordinary and without a string to his (invisible) bow. He is not an extrovert nor a narcissist, so he worries about the mental health of his mother when the going gets rough, and constantly encourages his dog Zero who is easily discouraged. These are the ways Jack manages his anxiety and keeps himself encouraged. But actually Jack is the most talented, generally with his empathy, but in particular in his relationship with Zero.

Jack’s father, Henry, detests the dog (and all other animals) for no good reason, proclaiming that the dog is aptly named due to his insignificance. Jack tries to defend Zero by countering that there are things less than zero, with Henry characteristically retorting: “Show me! Ha!”

Before we get the dynamic ball rolling, a few other points on the family. The adults have the following means of supporting themselves:

Henry writes scripts for the BBC and his plays are consistently panned by reviewers. Anything and everything in life and his immediate experience presents him with an opportunity to argue. Although he thinks of himself as especially observant and creative as a writer, the chip he carries on his shoulder blinds him to remembering the most basic facts. He particularly detests his brother-in-law Russell Parker, who is cool, calm, debonair, rich and enjoys goading Henry into arguments that he then uses in his occasional screen plays (Henry threatens to sue Russel for plagiarism), and Russell’s and his sister Celia’s destructive daughter Daisy (Henry constantly threatens to sue Russell for Daisy’s destructive activities, whether accomplished by Daisy herself — which of course gets attributed to the invisible Arry Awk — or by her goat, parrot, snake, maggots, etc.).

Laura writes an advice column under the pseudonym Stella Bright. Her primary items of advice involve Breathing and Positive Thinking. These items generally serve Laura well in her own functioning, but turn out to be inadequate when Unicorn House suffers an unexpected change.

Uncle Russell Parker is extraordinarily rich and uses money to solve his problems. He is also compassionate (as much as he can be under the circumstances of his wife and daughter, but he is the only one to specifically help Jack), cool, calm and debonair, and has the uncanny talent of talking police officers out of giving him speeding tickets.

Aunt Celia is extremely beautiful, never leaves the Knoll, is dreamy and reclusive, and progressively slips farther and farther into a new age fantasy world. She generally neglects Daisy. Here is a condensed description of the Parker family starting with Russell’s situation:

Uncle Parker was not finding life easy. Daisy and Billy Groat Gruff were both back at the Knoll, and his wife was still recovering from her trauma in the potting shed. Even under normal circumstances he was for all intents and purposes a single parent. Aunt Celia’s input was vanishingly small. She chose Daisy’s clothes, told her frequently that she was a genius, and allowed her free reign. Since Daisy’s activities to date had included scrawling poems on walls with indelible felt-tips, making random telephone calls, turning on all taps and setting fires, some might have thought this was permissiveness gone mad. Some husbands and fathers might have put their foot down.

Not Uncle Parker. He not only doted on his wife, he also believed her to be wise with a wisdom beyond that of ordinary mortals. No one else could imagine where he got this idea from. The Bagthorpes certainly could not. (pg. 92)

Speaking of the Bagthorpes, Henry shows his different parenting philosophy in this write-up when Uncle Parker gets his closest to violent rage (at yet another of Daisy’s arsenal, a mangy parrot with a foul vocabulary):

When his daughter had departed in search of Arry Awk, Uncle Parker sat for a long time gloomily weighing his options. He started at the inert form of the parrot’s leather-lidded eyes. He would have liked to wring its neck, but he didn’t have what it took. He was essentially a mild man. He had never so much as kicked the goat, despite all provocation. Nor had he ever raised a hand to Daisy. Mr. Bagthorpe said this was the root of all the trouble. All this airy fairy flim flam about the rights of the child and the evils of smacking had predictably produced a monster. He had himself frequently offered to administer a good thumping. (pp. 261-2)

Here we see the extremes of badness of fit, with neglect and abuse appearing in the wings to spread their shadows if the family falls too far apart (the YBs talk about Entropy). Daisy has a difficult (but charming) temperament, but is provided no limits or structure. Jack is slow to warm up but receives no encouragement from siblings, none from his father (except the insults to the dog), and his mother is too beleaguered to pay him much attention. And in the final analysis, there is the danger that Uncle Parker, in spite of all his permissiveness and easy going temperament, will end up wringing some bird’s neck, while Henry, always shouting and threatening aggression of some sort, will end up running away and abandoning the family himself (with the probable result that he gets arrested and jailed, much to the delight of his mother).

Is this Billy Goat Gruff eating Henry’s scripts or Zero having to tangle with the napkins while trying to get at the cake? No, it’s Cary being himself at an outdoor party.

OK, back from theory and on with the story.

One last character is the cook for Unicorn House, Mrs. Fosdyke (“Fozzy”), who is described as looking and moving like a hedgehog, is very judgmental, stubborn and superstitious, and since this makes her much like Henry, they avoid each other as much as possible. It is ironic that for all the attempts of the Bagthorpes to become rich and famous, the only two to do so (more famous than rich) are the marginal characters of Zero and Fozzy.

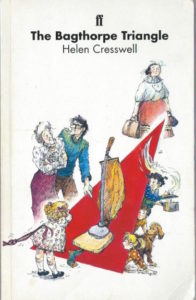

The cover of volume 8, the Bagthorpe Triangle (where people inexplicably disappear) shows the initial incident: the sucked up sock! At the top of the triangle is Laura, down the left side of the triangle is Henry and Grace facing off, Daisy at the bottom with the Hoover, with Rosie, Jack, Zero and Fozzy peering from the right.

To reveal the dynamics (as though they weren’t very apparent in the preceding volumes), let’s pick up the story in volumes 8 and 9. Two things occur: Laura has decided as the main bread-winner of the house, that husband and children are going to help with the housework, and she puts her foot down as a feminist. Henry of course will have nothing to do with this, but since he can’t always lock himself in his study and drink Scotch while writing, he uses the typical Henry ploy of manning the Hoover (vacuum cleaner) and immediately jamming it by “sucking up a sock.” He, of course, being a creative genius, knows nothing about how to unsuck a sock, so he feels justified in abandoning his chore and goes to town to eat a meal there. This, amidst the family hubbub about the sucked up sock, with Daisy topping the stir by gleefully dancing around while making up baby poem rhymes about “sucked-up-sockies”! (Enough to drive anyone mad, except the choreographer of the Row, Grace herself.)

In fact, this scene serves to unnerve the usually sensible and placid Laura, who emits a blood-curdling Primal Scream, locks herself in her room, and has trouble breathing or thinking of anything positive.

Nobody seems concerned about Laura’s mental state except Jack, and nobody knows what happened to Laura when she disappeared from her room (this was not the first disappearance in the story, so most of the Bagthorpe Clan was habituated to finding people missing). Then the second thing occurs: partly due to the disappearance of Laura, as well as other inexplicable happenings that Mrs Fosdyke doesn’t understand but comes up with iron-clad theories about, Fozzy ends up on the nightly news due to a mistaken bomb scare. It’s more complicated than we need detail here, but the result is that Fozzy is mistakenly reported to be the hero of a foiled bomb plot. On television, Fozzy’s strong opinions and strange beliefs about a wide range of subjects makes her a target for the tabloids “character of the month” irony fare and talk show circuit phenomenon.

So before Laura is settled back at Unicorn House, Fozzy gets swept into London with the paparazzi and media minder crew, put up in a fancy hotel without a kitchen, fitted for expensive clothes, taken to cocktail parties, and feted on the talk show circuit. While the tabloid industry tries to milk her as a quaint superstitious freak, Fozzy manages to foil the most adept interviewers who are used to pinning down the most elusive and clever guests, and shoots to meteoric popularity.

What the Bagthorpes had not realized was that as much as they looked down on and were annoyed by Fozzy, her cooking held the family together. Adding cooking (or just getting food) on top of the uncooperative lot of daily chaos then threatened to collapse the family (now we are into the last volume 9, Bagthorpes Battered), with William leading a plot by the YBs to run away. For which they need money:

The four Bagthorpe children are plotting to run away, but throughout their planning they keep running into the fact that they will need money and haven’t come up with a plan for getting money. William points out that they can’t go out of the country because they don’t have passports, and ports, airports and ferries are places they search for runaway people. So William concludes they need to hole up somewhere, to which Tess points out:

“For which we need money,” Tess said. “We’re going round in circles.”

They were, as so happened with the Bagthorpes. And being Bagthorpes round and round they would obsessively go until they came up with a solution. If there was a gene for obsession, they all had it — except for Jack. And nobody counted him. (pg. 107)

OK, I know the suspense is killing you, so back to Fozzy. It turns out that the expensive shoes hurt her, she doesn’t like the shwank crowd she is being kept in, she doesn’t like restaurant food, and she can’t do the one thing that keeps her sane — cook! So she tells her minder that she wants out, but her minder tells her she is under contract and obligated to complete it. At this point Fozzy becomes frantic with trying to figure out how to escape her imprisonment. She doesn’t even know what her address is or any of the transportation options of London, and she is afraid that if she sends a letter to Laura Bagthorpe Henry might intercept it and destroy it, so she writes to Stella Bright. Fearing that this will take too long to generate action, she ends up with the ultimate ploy — to send out an SOS at her next television interview. The way she takes over the TV show and goes Bat-Crazy is some inspired literature. Needless to say, it does get her rescued, but her return generates a frenzied train wreck of paparazzi, police, Uncle Parker, and the Bagthorpe pride. But most important of all (spoiler alert), Jack saves Fozzy.

Such is the world of Bagthorpe U., where soccer is played like rugby (my line). So that’s it. Keep reading, for reading good literature increases imagination and compassion. Just for good measure, here is another illustration of the Bagthorpe Clan. Top row: Alfred, Laura, Henry, Uncle Parker. Middle group: Grace, Rosie, Jack, Tess, William, Aunt Celia. Bottom Row: Fozzy, Zero, Daisy (with a fishbowl of still alive fish). Notice that Uncle Parker is the only one getting the better of Henry in this picture.

The End: Personality and Story

Now that we have mixed research and literature, let’s extrapolate on both ends.

The Bagthorpe Saga was a comic saga: it never had a bad end, but it never had a good end either. In fact, it reportedly had no end (according to the author, at least), but history shows that Book 9 was the last she wrote. In the end of the saga as reported, the crash that ruined the Bagthorpe pride was also the salvation of Fozzie’s reputation. If not a happy ending, at least some poetic justice. But most stories aren’t sagas — even epics have endings.

Personally I like the way Cressida Cowell ends the tragic-comic epic How to Train Your Dragon (book 12, pp. 459-60). Through the most grueling of earthly gruel, Hiccup Horrendous Haddock III manages to save both the humans and the dragons, achieving victory on the Island of Tomorrow:

THE HERO CARES NOT FOR A WILD WINTER’S STORM,

FOR IT CARRIES HIM SWIFT ON THE BACK OF THE WAVE,

ALL MAY BE LOST AND OUR HEARTS MAY BE WORN,

BUT A HERO…FIGHTS…FOREVER!

And if that moment doesn’t last forever … then it really ought to.

So that is where we will leave them, Hiccup and his friends: forever young, forever hopeful, singing their hearts out on the Island of Tomorrow.

BECAUSE…

If it doesn’t end well then it isn’t

Heroine from a rival tribe: yes, a Romeo and Juliet story among the rude northerners who once flew with the dragons!

THE END

The End for Real?

So how will it end for us? Well, we don’t know, but the research of Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess provides us with a hint that for some is also a warning: in adulthood, experience makes our temperament more like our parents’, largely overshadowing our childhood biological heritage (see link to Thomas’ obituary). Whether this is an act of free will, or the force of subconscious habits of mind (e.g. “Now that I am a parent, I sound like my mother!”), is one question. On the other hand, some of us have questioned the prejudices of our parents and have chosen paths fashioned from more humane values, neither retreating from the challenges of diversity (“slow to warm up” personality) nor prematurely rejected diversity (“difficult” personality), but using patience and courage to maintain the hope of a better future (thereby being a more “easy” personality with others and self, and maintaining a sustainable pace in order to achieve long-term results).

But to be more precise, Thomas finds that children and parents change through adulthood to be more like each other. For some, this could mean that a positive relationship makes both adult child and aging parent more easy to deal with. For all our sakes, we can only hope so!

Since we don’t know the meaning of a story until it ends, this is a call to make the end more meaningful.

For an example of how the human story better NOT end, here is research on how to create a terrorist by attacking the parent-child bond. Clinical psychologist Donald T. Saposnek details how the federal policy of separating children from parents at the border sows the seeds of violent gangs in this article published July 15, 2018.